When John Gartrell, then an intern for the Maryland State Archives, was tasked with looking for a commencement speech given by Martin Luther King Jr. at Maryland’s Morgan State University in 1958, he suspected there was one place he might find the talk in full — the Black press.

Gartrell, now director of the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African-American History and Culture at Duke University, reached out to the Baltimore Afro-American, a paper founded in 1892, which had the speech word for word. Even more thrilling for Gartrell was finding refrains King would use five years before the March on Washington.

“I was completely shocked,” said Gartrell. “I never knew Dr. King had used that before the March on Washington. And it struck me that if the Afro had not been there, and the Black press had not been there, that speech would have been lost to history.”

As Black History Month approaches, educators may be leaning on many lessons they taught in the past. But there are other understudied areas teachers can highlight to students next month — and at any time of the year.

Educators can start with the rich archives of the Black press, move on to talk about the history of Black-owned banks in America, and then discuss the contributions of Black engineers, from the first three-positioned traffic light to the longer-lasting filament that helps incandescent bulbs burn bright.

Black press: Chroniclers of Black history

Gartrell, who spent four years as the archivist for the Afro-American — or the Afro, as it is commonly known — has a special fondness for the newspaper. As the oldest African-American family-owned newspaper in the country, the Afro-American was founded by John Murphy, a former enslaved person in the Baltimore area who also served in the USCT (United States Colored Troops) during the Civil War, Gartrell said.

The paper even started a popular local environmental program called the Clean Block Program in 1934, launched by Murphy’s daughter, Frances Louise Murphy, to encourage students to clean up their block during the summer. Children would paint and clean the steps of row houses, plant flower boxes, and line streets with flags to compete for prizes ranging from trips to bicycles. The program was revived in 2017.

The paper's influence remains today.

The peak period for the Black press was between 1940 and the early 1970s, when printed newspapers including the Pittsburgh Courier and The Chicago Defender would detail news of the Black community, from election results to activities at local churches, Gartrell said. Black newspapers are still a rich resource today, he added.

While someone researching the American civil rights movement online may be able to pull up a piece from The New York Times and think they have the entire story, Gartrell said anyone working on stories about Black history should look for other materials, especially archived pieces from the Black press.

“When you want context and build-up about events such as the March on Washington, I don’t think there is a better resource than the Black press,” he said.

Black banks: Community investors

While banks are clearly a business, founders of Black-owned banks were typically motivated less by profit and more by community service, said Tim Todd, executive writer and historian with the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

These institutions would take depositors' money and reinvest it by lending funds to local businesses and people in their communities. Bank founders included Maggie Lena Walker, the first Black woman to establish a bank and serve as bank president when she launched the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. Walker said, in part, "Let us put our money together," Todd said.

“That is what real community banking is about,” said Todd, author of two books about Black banks including his most recent, "A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks." He added, “One of their strengths historically is they’ve been willing to do more relationship lending.”

The first Black-owned banks opened in the late 1800s, starting in Richmond, Virginia. Others opened in Washington, D.C., and then in the South, Todd said. As such, the topic can serve as a rich source for history curriculum on the Black community in the U.S. following emancipation and the post-Civil War Reconstruction period.

Prominent figures include Walker, whose home in Richmond is a National Historic Site; John Mitchell, Jr., a newspaper editor who founded the Mechanics Savings Bank in the early 1900s in Richmond; and Jesse Binga, whose home in Chicago was firebombed multiple times in the early 1900s.

“The risk that these individuals faced was not just about a business risk, but a very real physical risk as well,” Todd said.

With the economy suffering during the Great Depression, Black-owned banks were affected, too. But the Civil Rights Era brought a resurgence, with new banks flourishing, including the Tri-State Bank in Memphis, Tennessee. Founder Joseph Walker would post bail for demonstrators, Todd said.

But in the last 20 years, Black-owned bank numbers have dwindled precipitously from 48 in 2001 to just 18 remaining today, Todd said. According to a blog from Fundera, when credit unions are included, there are 42 Black-owned financial institutions in the U.S. today.

As Black-owned banks vanish, Todd worries their history fades, too. He added that people think Black-owned banks completely disappeared after the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, created after the Civil War, closed in 1874.

“But after the Freedman’s Bank failed, there is a rich and vibrant history of African American banking in the U.S.,” says Todd. “There are amazing stories about people who built up their communities in some difficult circumstances.”

Black engineers: Building America

John Brooks Slaughter can talk about Mark Dean, a Black engineer whose research led to the development of the IBM personal computer, or Mae Jemison, an engineer, physician, astronaut and the first Black woman to go to space. And he can also talk about how just 4% of students studying engineering in the U.S. are Black.

“The percentage of African American engineers in our colleges and universities studying engineering has not increased over the last 10 to 15 years,” Slaughter said.

The former chancellor of the University of Maryland, College Park, the first Black director of the National Science Foundation, and a current professor of education and engineering at the University of Southern California, Slaughter is also co-editor of “Changing the Face of Engineering: The African American Experience.” It’s a story he personally knows well.

As a young child, Slaughter remembers “tinkering” with projects he would find in Popular Mechanics magazine. He built a camera, learned how to repair radios and designed other electrical devices before realizing, by the 8th grade, he wanted to become an electrical engineer.

But as he entered high school, Slaughter was sidelined by counselors and teachers into a trade school education, he said.

“I was not knowledgeable enough to know that I wasn’t being prepared for what I wanted to do,” he said. “So I had to go to a liberal arts college and take the courses I should have taken in high school, and that prepared me.”

Today, he can point to many Black engineers who have made important contributions to American science, including Jemison and Dean. But he believes schools are not encouraging minority students enough to pursue engineering, and he worries that if they are not motivated, the U.S. won't stay competitive in science and technology fields.

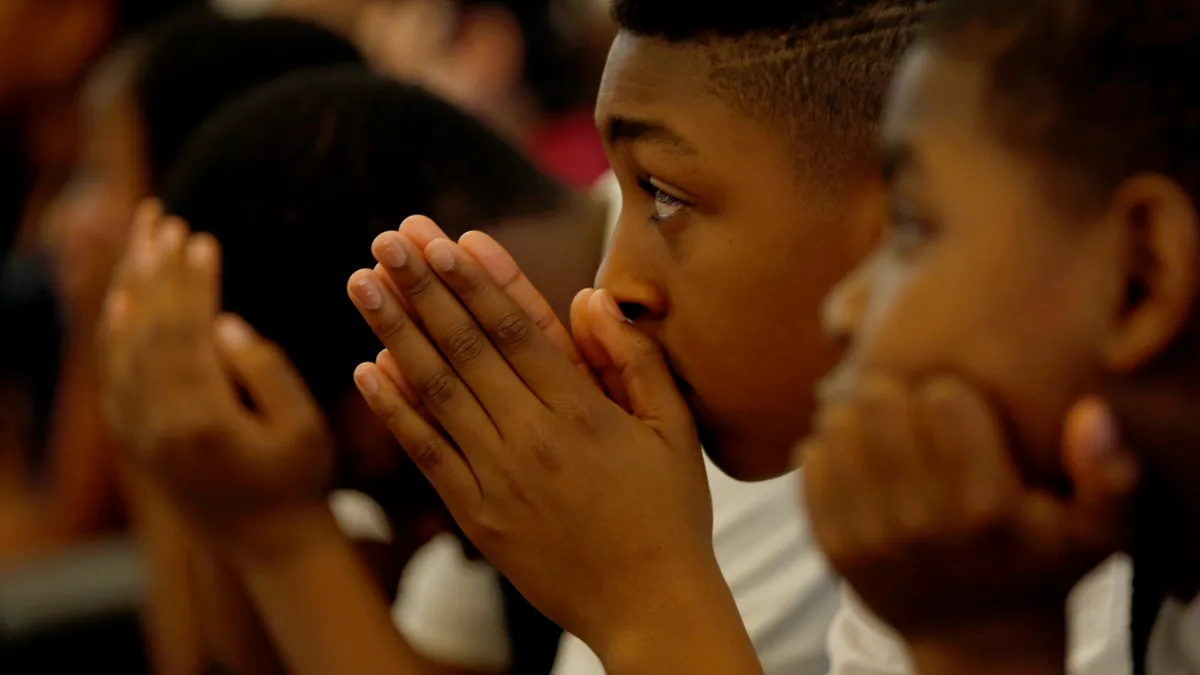

Pointing students in the direction of math and other classes that can prepare them to pursue this field is one step, but so too is talking to K-12 learners about the contributions of Black engineers throughout history.

“We need to have Black and brown students prepare to become engineers,” he says. “They need to know this is an opportunity for them as well as anyone else. And we need to show them that there are people who have paved the way, and what they’ve accomplished.”