Thanksgiving was initially made a national holiday by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, as a means of celebrating the Union's victory at Gettysburg. Despite the long history of celebrations to give thanks that existed in many cultures, the "first" official American Thanksgiving is, however, often recognized as a feast between the pilgrims at Plymouth, MA, and the Wampanoag tribe of Native Americans.

As is often the case with history, we have a tendency to look back at that event without perspective — particularly in the classroom, where time and resource constraints, as well as controversies over subject matter, can often lead to inaccuracy. While the Thanksgiving holiday is also seen as a time of celebration and being with loved ones, it's also a reminder of an event preceding centuries of tragedy for Native Americans.

It is often said that failing to remember the past leaves us doomed to repeat its mistakes, and there are a number of resources available from organizations like the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian and the Plimoth Plantation to help educators present both sides of the story in age-appropriate manners. But the approach is often just as important as content in the classroom.

Here are three tips to help keep Thanksgiving lessons balanced.

Avoid generalized depictions of Native Americans

Stereotypical and caricatured Native Americans have been prevalent around and beyond Thanksgiving for years. Chief among these depictions is the Native American man wearing a feathered headdress. Aside from being offensive, this stereotype is historically inaccurate for the Wampanoag tribe, which inhabited the Plymouth area. According to the Plimoth Plantation, men in the tribe typically wore deerskin breechcloths, with flaps hanging down in the front and back, as well as leggings and moccasinash when necessary for protection. When it was cold, they also wore mantles made from various animal hides, and women typically wore deerskin skirts.

While there are statues and illustrations depicting Wampanoag with feathers in their hair, the stereotypical feathered headdress was more typical of tribes in the Plains and primarily worn as a symbol of respect by men who had earned it within their tribe. It was similar, say, to a war medal that might be worn by a veteran of the military today. As a result, it's not hard to see how activities that involve making a headdress out of construction paper would be offensive to Native Americans regardless of historical accuracy.

The most important thing on this front, perhaps, is ensuring that students understand that there were numerous tribes, all with their own cultures, as opposed to a single type of Native American.

Put modern challenges facing Native Americans in context

It may seem silly to note, but Native Americans are still very much in existence today. Unfortunately, it's a detail that can be overshadowed if all talk of indigenous people is focused on the past. Educators should be sure to provide context in Thanksgiving lessons for the long-term consequences — which include plague, war, slavery, dispossession of lands, and genocide — faced by Native Americans as a result of European settlement.

One way to do this, according to a document from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, is to encourage younger students to think critically about how those factors have impacted resources used by Native Americans, and what, if anything, is being done to promote their renewal. Older students, meanwhile, can consider how European settlement and, later on, federal policies impacted traditions and connections to homelands.

Be aware that many Native Americans see Thanksgiving as a day of mourning

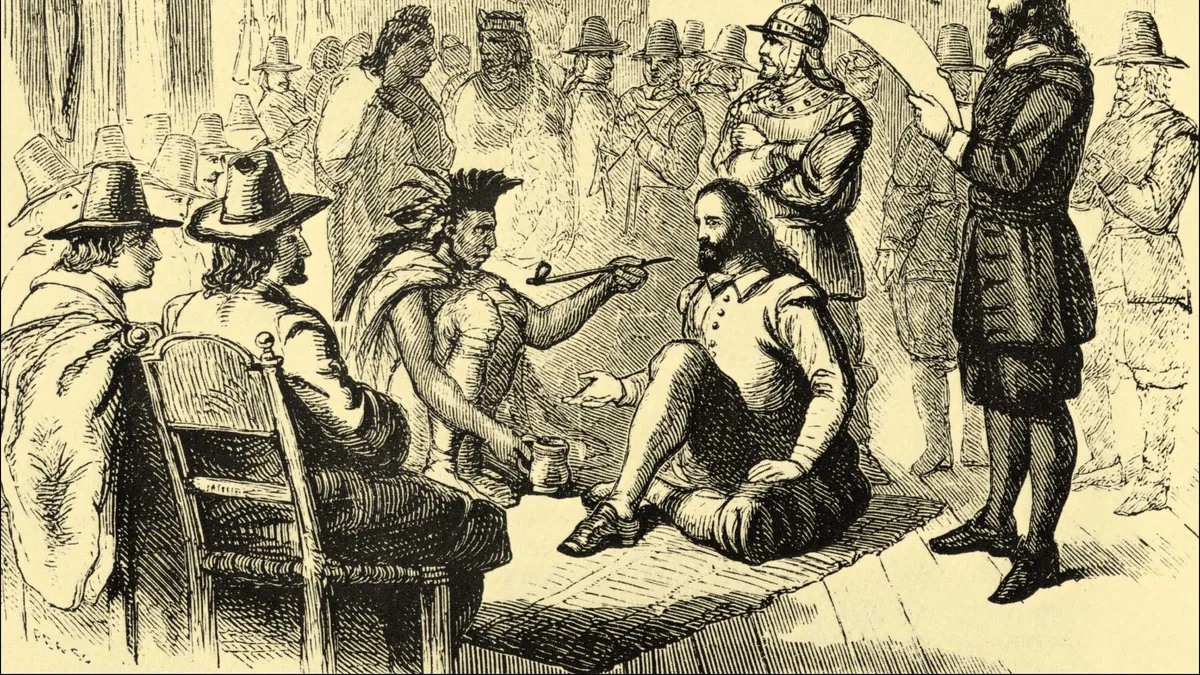

In a 2011 story published by Indian Country Today Media Network, Michelle Tirado details the Wampanoag side of the encounter traditionally recognized as the "first" Thanksgiving. In the spring of 1621, the pilgrims had entered into "a treaty of mutual protection" with Pokanoket Wampanoag leader Massasoit. The article states that members of the tribe has also shared strategies for planting corn, fishing, and gathering berries and nuts.

Sometime around September or October of that year, during a pilgrim hunting session following a successful harvest, Massasoit was alarmed by the amount of gunfire coming from the village and went to investigate with 90 warriors. Upon their arrival at the village, the article says, the Wampanoag were invited to join the pilgrims in their harvest feast, but the resulting lack of food for everyone compelled Massasoit to send out his own hunting party, which brought back five deer. Thus, Thanksgiving developed a tradition of sharing.

But Tirado writes that the event is now seen as bittersweet due to the hardships faced by Native Americans in the centuries since Europeans came to the U.S. Following Wampanoag Wamsutta James' disinvitation from Massachusetts' 350th anniversary celebration of the pilgrims' arrival in 1970, due to the content of a speech he was to deliver, a National Day of Mourning protest has taken place annually on Thanksgiving Day near Plymouth Rock.

Would you like to see more education news like this in your inbox on a daily basis? Subscribe to our Education Dive email newsletter! You may also want to read Education Dive's look at what the future holds for K-12 ed tech.