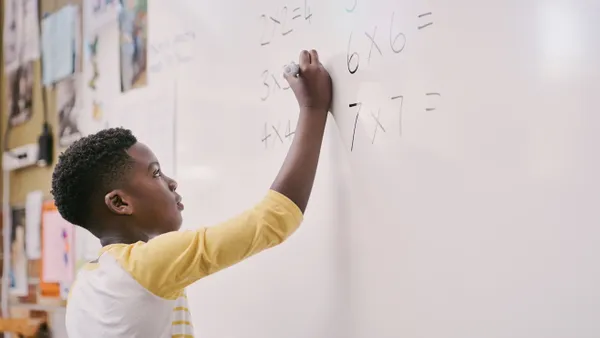

Robert Dillon knows any plan to bring back 2,700 students this fall can’t be boilerplate. That’s why the director of innovative learning for The School District of University City in Missouri instead envisions a scenario that dips, dives, moves forward and back — all throughout the year.

To him, the best solution is one that’s flexible, so if students have to learn from home again for a period of time, their learning needs are still met.

“We’re trying not to think so much of a Plan A or Plan B, but what does it look like when you’re in a phase?” he told Education Dive. “Everyone learning from home? We don’t think that’s what’s best for kids. But learning from what we’re doing now, and making it the best and as robust as we can, that’s one piece of the puzzle.”

For many districts, summer has already started. And typically, curriculum directors and superintendents have fall plans fairly set. Although many states are loosening restrictions, school districts remain watchful. While some are considering how schools will look when they reopen, many believe they need to prepare for scenarios that send them home again.

The goal, though, is to ensure education, wherever that happens, is not disrupted.

Parallel tracks for instruction

For Dillon, that goal means looking at building two pathways at once — a scenario where students are learning in physical classrooms and a parallel one that’s online.

“I think all districts have to consider what it looks like to have a full-time virtual academy,” Dillon said. “I think all schools going forward have to have some kind of truly robust, virtual academy and figure out how to staff it.”

In the Douglas County School District in Castle Rock, Colorado, Superintendent Thomas S. Tucker wants options that protect students' ability to learn alongside teacher bandwidth and yet are flexible enough to weather the continuing impact of COVID-19.

Tucker, who was the 2016 American Association of School Administrators National Superintendent of the Year, is looking at multiple scenarios, including one where some students are online a couple of days a week, with another group in classrooms, and then the two switch.

“We are planning — the verbs are very important — for a traditional fall opening in time, but we’re also preparing to continue remote teaching and learning,” he told Education Dive. “So we’re going to spend the summer paying close attention to how COVID-19 is impacting our community and our state, and our hope is to have a regular opening for the fall semester. But we are preparing for different scenarios.”

A phased-in approach

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines called "Considerations for Schools" to help guide districts on the best path forward for the fall. Without telling administrators what to do, they offer three scenarios, ranging from the lowest to highest risk. The thread through all three scenarios is density — students and educators at home isolated, as opposed to everyone at school together.

Administrators appear to be eyeing a middle ground, including everything from one-way hallways to meals eaten at desks, and even certain grades allowed to come back, while others stay in distance learning setups.

Dillon said even 50% attendance on the first day of school is not likely in his district. Instead, the district is looking more at starting the school year with just 10-15% capacity in a building, and then remaining flexible enough so numbers could increase or decrease depending on COVID-19.

"What would it look like for kindergarten and 1st grade coming back to the building, and then recognizing that the first day, one of our kids and family are contagious [and] we need to shut the building for a period,” he said. “I think this is not linear. I think we have zero students, and then 10%, then 50%, then zero and then 10% again. That is going to be our first semester.”

This will ultimately impact how curriculum is planned and what resources are invested in, as any expectations and tools will need to be flexible to adjust to any of these scenarios.

Nice to have vs. have to have

While building two pathways may be the ideal, administrators believe their budgets, designed to support one pathway, are going be cut due to lower tax revenues related to the coronavirus. And with recommendations that class sizes be smaller so students and educators can continue to socially distance in a face-to-face environment, many administrators are wondering how can they hire more teachers to support that shift.

Matthew Joseph, director of curriculum, instruction and assessment for Leicester Public Schools in Massachusetts, said his decisions based on budget cuts will come to choosing between things he would like to have for his district and what he knows he has to have. For example, while he would like class sizes to come down to 20 students, he’s mandated to have them at least under 30, but not smaller than that.

And then there’s a question of budget lines where he could save funds. That might include bussing, for example, Joseph said, and whether children who live within a mile of school can do without bussing if that saves the district $100,000.

“We’re looking at making a needs-based budget and looking at our priorities, our must-haves, nice-to-haves and our wish list,” he told Education Dive. “There are certain things we have to have. Bussing is a must-have. Distance is a nice to have."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards