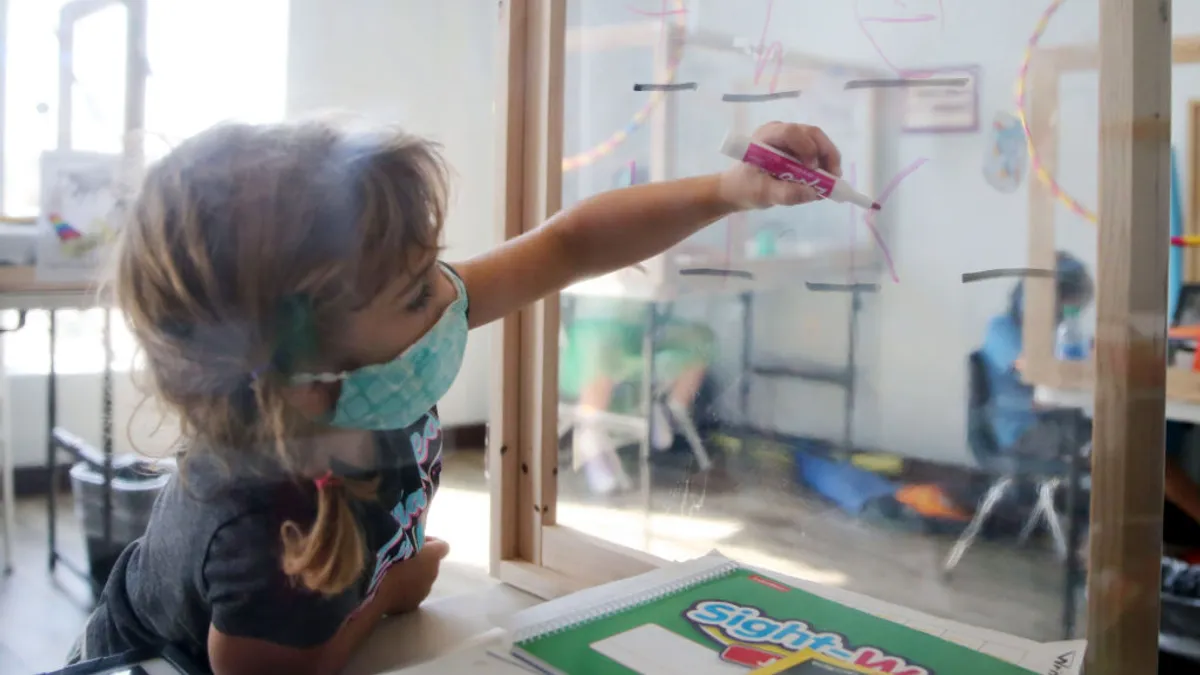

A student in mental health or behavioral crisis can display obvious actions such as punching or screaming. But other mental health struggles can be hidden, including suicidal ideations, depression and anxiety. As more students return to school after long periods of virtual learning, schools need to be prepared to respond strategically to all types of intensive behaviors, say school psychology experts.

The transition from the home to school after such a long on-campus absence may be very difficult for some students, said Patrice Leverett, an assistant professor of school psychology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and an expert in crisis response.

One universal and preventative recommendation for schools is to dedicate time to acclimating all students to being back in the school environment and acknowledging the hardships students faced this past year.

“Ask clarifying questions about how they're feeling and make sure that you're understanding what their perspectives are,” Leverett said. “Also creating a judgment-free zone, and not minimizing their experience. Sometimes we think, ‘Oh, kids, they'll bounce back and they're resilient and it's totally fine,’ but kids have hard times just like adults, and their feelings are valid and you shouldn't criticize or minimize those things.”

The pandemic’s toll on student mental health is a major concern for school leaders. Mental health-related emergency visits for children ages 5-11 increased by 24% between April and October 2020, compared to the year before, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additionally, emergency visits for children ages 12-17 increased by 31%, the study showed.

Here are more targeted ways schools can support students in crisis.

Have a response plan

When responding to a highly charged situation where a student may be acting violent or agitated, there should be pre-established protocols. The designation of a crisis response team can take the guesswork out of who responds to an emergency and how, said Jessica Dirsmith, a clinical assistant professor of school psychology at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania's 2017 School Psychologist of the Year.

Additionally, school staffs should be trained in trauma-informed practices, Dirsmith said. That professional development can be essential for when a student’s anger is escalating. Instead of making snap decisions in the heat of the moment, training in trauma-informed decision-making can help teachers rely on evidence-based techniques to reduce behavioral concerns, she said.

Teaching students acceptable behaviors and how to self-regulate, as well as having a multi-tiered system of support, should also be part of preventative and response plans, Leverett said. Dirsmith also recommends universal mental health screeners and data analysis, such as attendance, discipline and academic records, to identify students who are struggling with mental health challenges.

“The reality is we don't really know what students are going through until they tell us, and so we have to be open to hearing them out and honoring and trusting their perspectives and not necessarily rushing in to save them, but to just say, ‘I'm here for you if you need me, and let me know what I can do to support you,’” Leverett said.

Avoid punitive reactions

Threatening detention when a student is in immediate crisis is not effective and can actually create a heightened level of agitation or despair, Leverett said.

“I think sometimes when we're in a situation where a student is particularly escalated, there can sometimes be a little bit of defensiveness [from educators],” Leverett said. “If we can stay calm in that situation and kind of model calm, that can sometimes help the student re-regulate by just being in a calmer environment again.”

Leverett also recommends against making physical contact with a student in distress because it may be unknown if touching the student would trigger elevated behaviors because of past traumas. If the student in crisis needs to be physically guided, it is best to ask their permission first, she said.

If there is concern about safety and the student in crisis won’t voluntarily leave a classroom, school staff can guide other students out of the room, Dirsmith said.

In the midst of a tense situation, avoid accusatory language or threats of discipline. Instead, validate the student's feelings without validating the behavior and allow them to recover from the intense situation, Dirsmith said. Decisions about consequences or increased interventions can always be made after the escalated situation passes, she added.

“When a child is in the fight or flight mode, they're really looking to gain some form of control so [adults] being controlling is not the best approach,” Dirsmith said. “Being empathetic and giving choices if that's an option, could be very beneficial to deescalate [the situation].”

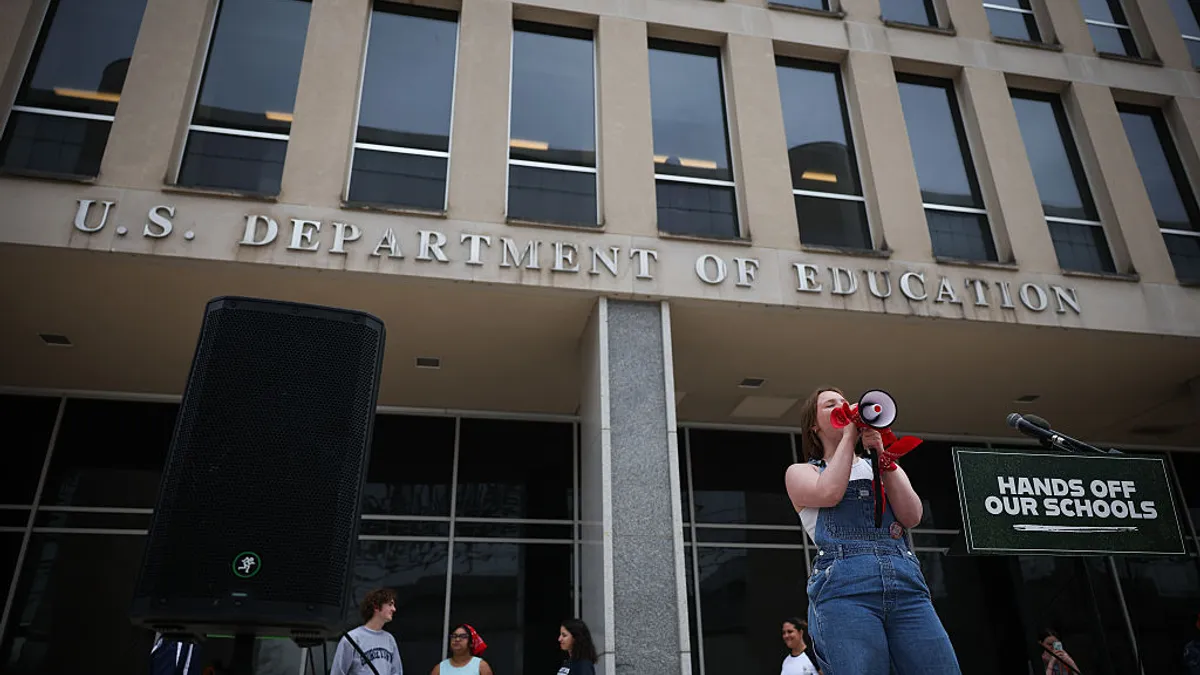

Form community partnerships

Having pre-established relationships with community providers can benefit schools as they respond to student mental health needs, particularly if a student’s level of need is beyond what the school can provide. For example, integrated mental health teams can help facilitate appointments for students to meet with counselors either within the school or with a community provider, Dirsmith said.

The pandemic has pulled schools and their community partners closer together as governments, health providers and organizations work collaboratively to address critical needs as a result of COVID-19. For example, My Brother’s Keeper in Las Vegas has provided resources regarding mental health supports, computer and internet access, and more, Leverett said.

“There was already a hope to kind of integrate more community and school partnerships previously, but it's just become an absolute necessity,” Leverett said. “Now, the needs are just too great to be managed within this school building.”