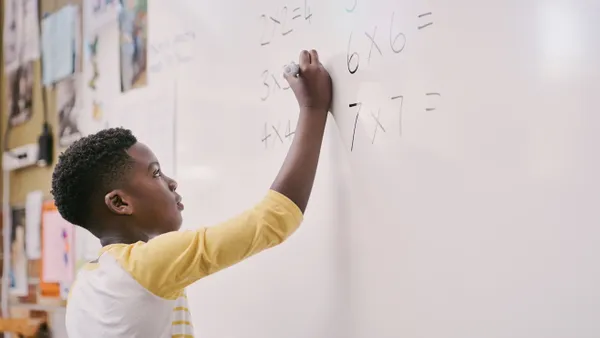

Arkansas is working to provide support for students with dyslexia through efforts to retrain teachers and change the way reading instruction is delivered, with a focus on methods based on the science of how students learn to read.

That shift to change how reading instruction is served isn't happening in every state, however, despite dyslexia affecting one in 10 people worldwide, according to a 2014 report from Dyslexia International. In some cases, parents say they can’t even use the word when speaking with their child’s school, Nancy Duggan, executive director of Decoding Dyslexia Massachusetts, told Education Dive.

Duggan has heard from parents who meet with special education teachers, hearing educators and others at schools react when parents say “the 'D' word,” she said. “A parent told me, ‘We said it, and everyone took a shift back.’”

But many districts, from Arkansas to Virginia and Maryland, feel differently. There, lawmakers, district leaders and educators are working to change how students are supported and disrupt the way they've been taught to read.

Loudoun County Public Schools (Virginia)

In Virginia's Loudoun County Public Schools, a pilot using the multi-sensory Orton-Gillingham structured language approach is making its way not just to students who've been identified as dyslexic, but to their peers, Lorraine Hightower, a certified dyslexia advocate and consultant based in Lansdowne, Virginia, told Education Dive.

Orton-Gillingham is an approach that is steeped in phonics but incorporates multiple inputs, from visual to tactile, in teaching students to read. Facilitators first trained reading specialists and special education teachers in the approach, which uses multiple methods including visual and auditory keys.

“And now it’s expanded to the general ed, administrators and anyone who would like to participate,” said Hightower, who is the former chairwoman of the district’s Special Education Advisory Committee. “We actually have general education teachers seeing significant results with ELL students and neurotypical kids.”

St. Mary’s County Public Schools (Maryland)

A different approach is in play at St. Mary’s County Public Schools (SMCPS) in Maryland. The state adopted guidance in 2016 that told schools that they could actually start saying the word "dyslexia" while also giving direction on how to identify it and support students through instruction.

To that effect, SMCPS has adopted the Wilson Reading System, a structured literacy program that is a “one-on-one intensive intervention,” Laura Schultz, a state leader in Decoding Dyslexia Maryland, told Education Dive.

Through the program, educators are being retrained in literacy instruction, and while it's not a prevention framework, it is designed to help students already struggling, Schultz said. Students receiving the intervention are those with “…word-level deficits and intensive and structured literacy instruction due to a language-based learning disability, such as dyslexia,” wrote SMCPS in its 2018 Master Plan Annual Update.

Hazen School District (Arkansas)

Arkansas has made statewide changes to shift the way it approaches literacy instruction, Audie Alumbaugh, co-founder of the Arkansas Dyslexia Support Group and a retired STEM Master Teacher in the Department of Teaching and Learning at the University of Central Arkansas, told Education Dive.

The state is now using a structured literacy approach called the Science of Reading, tying literacy instruction to how the brain actually learns the written word, she said. “It’s kind of like the way we teach math,” said Alumbaugh. “We teach numbers and number sense and then how to manipulate numbers to get them to do things we need.”

The state’s General Assembly passed the Right to Read Act in 2017, requiring all K-6 teachers and all K-12 special education teachers to demonstrate their ability to use science-based reading instruction by the 2021-22 school year. Some districts are moving faster, including the Hazen School District, which has already had the Science of Reading system in place for a couple of years, said Alumbaugh.

“It’s been so successful, they have had to let the special ed teacher go because there weren’t enough special ed referrals,” she said.

To Alumbaugh, the time has come for educators — not just in Arkansas — to stop blaming other causes for a child’s inability to read, such as their lack of exposure to books before they start school. She believes the real culprit for children who struggle is the way they’ve been taught to read. For her, the shift to a science-based literacy approach can’t happen fast enough.

"As educators, we always have an excuse as to why something can’t happen,” she said. “It’s time for excuses to go away and science to take its place.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards