WASHINGTON, D.C. — A ballroom full of superintendents and other educators gathering from across the country just returned from lunch break when they were asked to stand up for a stretch.

“We are family!” the group of district leaders, dressed in business attire, began singing loudly and swaying to their steady clap. “I got my family with me!”

Superintendents and experts were in a Washington, D.C., suburb this week for the AASA | The School Superintendents Association Fall 2019 Social and Emotional Learning Cohort meeting, and taking a meaningful and mindful break from the three-day conference was a way to put into practice what they had been discussing: social-emotional learning.

With leaders' interest in the practice growing, SEL integration is still in its infancy in many districts, while others are a few years into full implementation.

Here are considerations discussed by leaders nationwide who have implemented SEL initiatives.

Make SEL practices culturally considerate for far-reaching impact

After a young student from Superintendent Luvelle Brown’s Ithaca City School District told him he never knew heroes could be black, Brown (pictured above) took a serious look at one of his schools and discovered the only African American role models on the walls were athletes from the 1970s. Missing from the walls and the library shelves were culturally relevant figures and texts such as the Black Panther.

“Walk through your spaces and look at the posters and see what messages they’re sending,” Brown said.

In Anthony Swentosky’s relatively small Teton County School District in New Jersey, the racial and cultural dichotomy, and the resulting achievement gap, is “very obvious.” Putting in place restorative justice practices and addressing self-segregation in clubs and afterschool activities was critical.

A series of roundtable discussions with parents, teachers and students resulted in stakeholders producing a list of themes and suggestions district leadership took into account when addressing the problem, said the director of educational services.

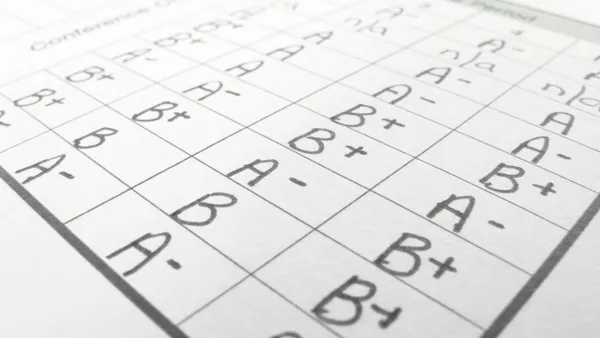

If students are to receive SEL grades on their report cards, as some districts are doing, be sure to take into account the inequity that could result if cultural context is not factored in correctly, one speaker said.

“How one student engages in disagreement can be very different from how another student engages in disagreement,” pointed out Lisa Xagas, director of student services for Illinois’ Naperville District 203. “In order to get rid of inequity in reporting SEL skills, don’t report deficits, but report relative growth and contextualize.”

Get stakeholder buy-in, especially in initial stages

Getting stakeholder buy-in from communities can be as difficult as it is critical. Knowing what your community responds positively to can be key in dispelling resistance around SEL.

In Superintendent Kathi Weight’s Steilacoom Historical School District in Washington, where many students are from military families, SEL was initially viewed by the community as “fluff,” with parents and even teachers reluctant to address mental health issues.

“We tied it for both the adults and children to neuro-education and had so much more buy-in,” Weight said. “Connecting the brain science to how we learn and translate skills into other situations was a huge success for us.”

Leveraging community partnerships “to get the word out” also worked to dispel stigma, she added.

Another way to increase buy-in is to have teachers contribute to the SEL curriculum. “We built a curriculum team and approached it the same way we built academic curriculum,” Xagas said.

“We came at it with the spin of, ‘What does this do for our academic work?’” said Christine Igoe, assistant superintendent of Naperville District 203. “We said, ‘If we don’t address these SEL skills, then you can’t reach your content goals.’”

For principals reluctant to integrate SEL into curriculum, linking its success to the rest of their responsibilities can do the trick, Xagas said.

“It took us a while to draw connections to make them realize that SEL was not just something else on their plate, that it was their plate on which everything else rested,” she said.

Start by educating the educators

Many educators say SEL work begins with the adults, and that addressing teachers’ SEL capacities before students’ is a game-changer. If, Igoe said, she could get a do-over, she “would start with our staff and their abilities to build their own self-competencies and spend a lot of time teaching them to care for themselves first.”

Encouraging comprehensive professional development and the exchange of ideas and best practices between educators — even if it’s over social media and through a district-wide hashtag — can keep momentum going.

Shift language to establish a formative narrative

“You can’t just buy a single curriculum and say, ‘We’ve done it,’ ” said Superintendent Sheldon Berman of Andover Public Schools in Massachusetts. “It’s about … what we communicate on a daily basis. The classroom and school have to be consistent in its message with the SEL programs that we’re implementing.”

Weight said language in her district shifted from “Why aren’t our students coming in with these skills?” to “OK, how do we build an environment that promotes skill building?”

Framing SEL for both students and teachers as strength-based and formative instead of deficit-based can influence how well it is received, experts at the meeting said. For example, instead of saying “We’re at this low grade and we need to improve it,” identify where improvements can be made and how skills can be enhanced.

This applies especially to trauma-informed practices in communities of color, particularly with black boys and young men.

“The challenge is getting black boys to understand that they already have the skill set around grit and perseverance,” says Eric Gallien, superintendent of Racine Unified School District in Wisconsin. “We’re trying to teach staff about trauma-informed care so that they don’t approach students from a perspective of deficit, but from a perspective that they already have certain amounts of grit and perseverance because of what they’ve gone through.”