As pandemic-related school closures near their one-year mark, reopening remains contentious within some communities. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a COVID-19 operational strategy for K-12 schools, many say reopening is more than a science-based decision informed by virus transmission and other factors — it is also a matter of trust.

This is especially true for Black and brown families, which are disproportionately represented in COVID-19’s death toll and may feel more at risk. That hesitancy could also resonate with Black teachers, who, according to a National Education Association survey released in February, are half as likely to have been vaccinated as their White counterparts.

“I think that they need leadership,” said Michael Conner, superintendent of Middletown Public Schools in Connecticut.

Communication and messaging

One of the top strategies superintendents said was key to building trust was two-way communication between parents and district leadership.

For example, Conner said he gets approximately 300 emails per day — many from parents asking questions on topics ranging from learning models to student mental health and trauma. Responding to those parents, he said, has “become a second job,” but an important one that makes parents feel heard.

“That provides a sense of security in this environment,” Conner said.

Administering surveys is another way to make parents feel heard. “We asked about every question you could think of,” said Glenn Robbins, superintendent of Brigantine Public Schools in New Jersey. His district is approximately 85% in-person and 15% remote, compared to 70% in-person and 30% remote in August.

It’s also important to communicate decisions in the most simplistic terms, providing the “why” behind those decisions, Conner said.

Vernacular is important, too, he added — and something that has shifted in Middletown with the availability of new research. “I’ve been trying to change the vernacular to ‘infection control,’” he said. “Now it’s about ensuring that we adhere to those protocols with a high level of integrity.”

Consultation across communities

While district leaders acknowledge a return to in-person is important, they’re also cognizant that Black and brown families should not be pushed or feel pressured to send their children if they are not comfortable. On the other hand, some families, like those in Robbins’ district, may prefer to return to school because of financial strain and the need to return to work.

There should be a range of learning models available for families to match these varied needs, superintendents interviewed for this article said. “We have to be aware of the conditions that our families are in and we have to ensure that families have a voice and option of what’s best for them,” said Conner, whose students are a mix of racial and ethnic backgrounds.

And before making final decisions, Conner said he consults communities from across the spectrum. “A lot of the times I receive emails from one demographic subgroup, [and] I have to intentionally reach out to other subgroups about what they’re feeling” to balance the viewpoints he takes into consideration.

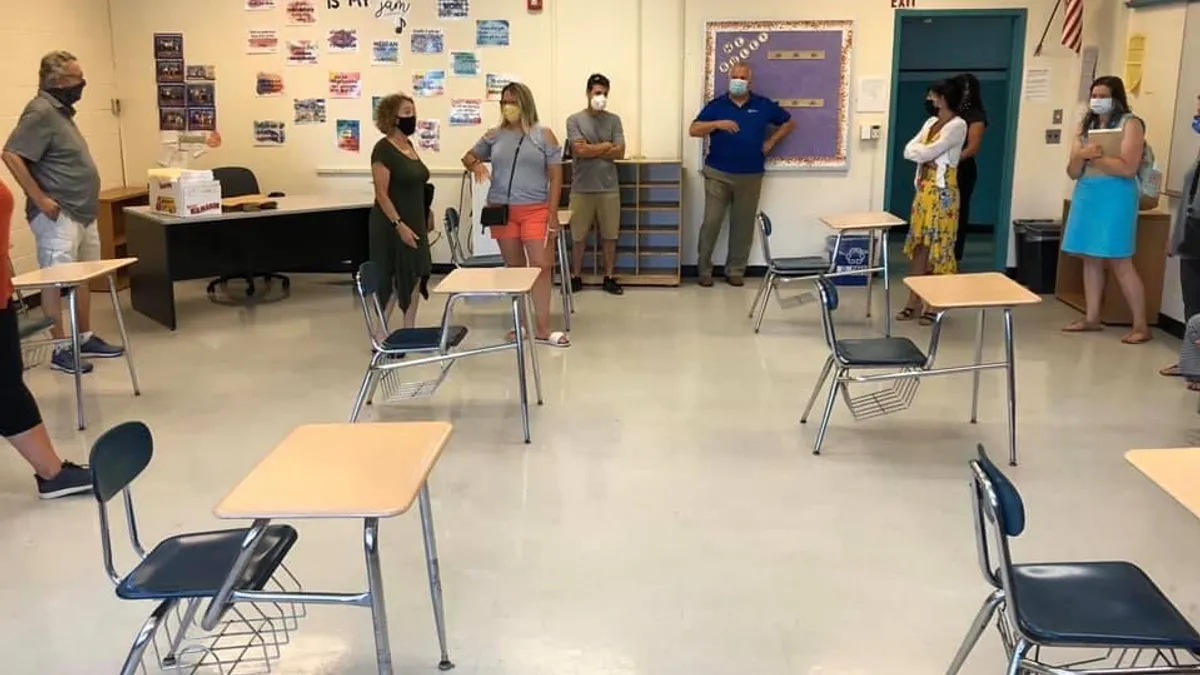

To build buy-in, parents can also be directly involved in the decision-making process around mitigation measures. Brigantine Public School District, for example, held a town-hall style meeting with parents and administrators to discuss operational strategies, like the procedures for walking in hallways and sitting in a classroom. The district even went so far as to invite a representative of its bus company to speak about protective measures in place for student transportation.

Parents were then able to give insight about what to tweak in the proposed mitigation measures. "We told them, 'Now we need your help,'" Robbins said. "The purpose was to give a design-thinking challenge through an empathetic approach ... [and] to build something from multiple lenses."

In Texas’ Premont Independent School District, Superintendent Steve VanMatre said teachers and students were also given voice in some areas. “Once we were able to include them and have them be a part of developing mitigation strategies they became much more comfortable with coming back to work absent of a vaccine,” VanMatre said.

Students at Premont’s PK-5 campus, for example, maintain social distancing in hallways and common areas by wearing hula hoops — a concept introduced by teachers.

“It worked very well,” the superintendent said. “They’ve gotten to the point where they don’t want their hula hoop touched by another hula hoop.”

Mitigation measures

Having in place and following other mitigation measures has been important in building trust, as well.

“One of the things that we’ve been communicating is the latest CDC research, that kids are really safe at school, it’s one of the safest places for them to be,” said VanMatre.

Robbins’ district uses air purifiers and cleaning systems before, during and after school, among other measures.

Conner’s district, where a number of families have expressed interest in shifting back to in-person learning, has in place asymptomatic testing on a weekly basis, rapid symptomatic testing for staff and students with results available in 15 minutes, thermal scans to take temperature, and desk shields for adults and students.

“A lot of Black and brown families are saying that they feel their child will be safe [in school],” Conner said, adding his district hasn’t recorded any cases of student-to-student transmission of the virus.

Visible and available

For VanMatre’s rural district, another strategy that has worked was in place long before the pandemic: schools’ central role in the tight-knit community.

With the recent winter storm devastating Texas and causing water, heat and power outages, Premont offered its school buses to transport citizens to neighboring community shelters. It’s also providing blankets to some families.

“When you do those things for them, then it helps when we want them to do things for us, such as trust us to send their children back to school,” he said. “It’s a continuum of services from teaching a kid to read to taking them to a shelter when they're in their 60s that [fills] this kind of need.”