Dive Brief:

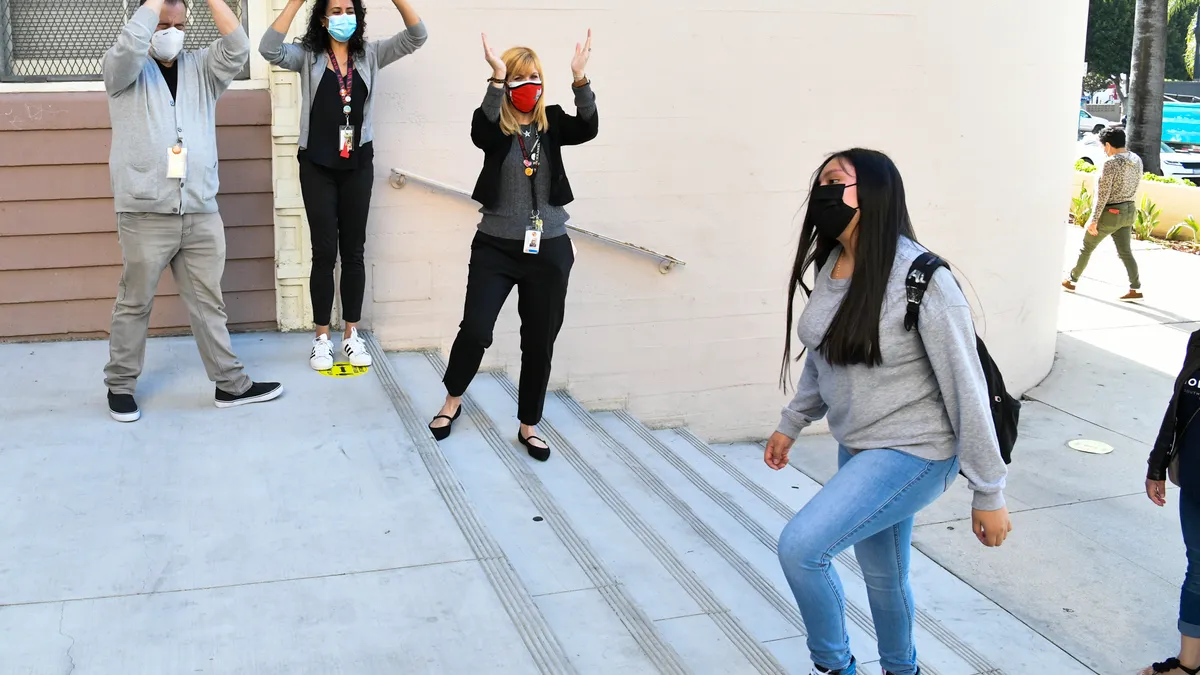

- Incorporating trauma-informed practices into schools will not solve the hardships students and staff experience — but will help schools be supportive, welcoming and safe places where both children and educators want to spend time, said panelists during a Wednesday webinar hosted by the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- From helping adults find restorative moments during the day to allowing students to sit in the principal's chair for a few minutes, there are multiple approaches to creating healthy school communities. Building and maintaining strong relationships should be at the core of trauma-responsive efforts, said panelist Aysha Upchurch, a lecturer on education and artist in residence at the graduate school.

- As school systems seek ways to retain and recruit staff and to increase student engagement, they should acknowledge the duress people are under and find strategies to empower students and staff, as well as add joyful moments to the day, the panelists said.

Dive Insight:

One challenge schools face when addressing trauma is the wide variety of adverse experiences that in turn result in a range of reactions. Some students might show anger or sadness, while others may suffer in ways not obvious.

"We really have to resist the temptation to fall into the kind of deficit thinking trap and ask, 'What's wrong with those kids?'" said Mark Tappan, a professor of education at Colby College, in Maine. "And instead, we really have to ask what's happened in their life, in and out of school, that has contributed to how they're acting in the classroom and in the school at large."

For school and district staff, there's concern about secondary trauma, or feelings of despair when trying to support students and families experiencing difficult times.

The panelists shared four specific approaches to addressing trauma in schools:

- Design spaces with a trauma lens. Upchurch recommends schools be purposeful when planning learning areas so they are welcoming and safe. Those spaces and materials should try to avoid triggers for trauma, such as content or activities that could be isolating.

"You are designing it intentionally, considering that maybe some of the content and maybe some of the activities might not be just an easy grab for all students," Upchurch said. "It is an awareness that students and even other adults in the building or in the sphere are coming from very different perspectives and experiences." - Bring joy to the school day. Tappan recommended a strategy called "Somedays," used in small, rural schools where every student and teacher in a school gets to answer the prompt, "Someday in school, I would like to …." He said students have asked to have recess with siblings, teach a kindergarten class and sit at the principal's desk and eat M&Ms.

There are "really interesting sort of fun things that kids wanted to do to make school kind of a place that is meaningful for them," Tappan said. "It's building the happiness of students who come to school with something to look forward to." - Empower students and staff. One feature of trauma is disempowerment and a disconnect from one's self, said webinar host Uche Amaechi, a lecturer on education at Harvard Graduate School of Education. This is why it's recommended to use strategies to help students and staff reconnect with themselves and each other, the panelists said.

Upchurch said giving student's agency and using a "healing-centered educational design" can be especially effective as students recover from pandemic-related school closures. - Allow time for collaboration. The panelists said schools should support collaborative efforts within school buildings, such as trusting relationships between teachers and students, teachers and administrators, school staff and families, and teachers working with other teachers and staff members.

Schools should also seek to build partnerships with outside organizations as well, the panelists said

"I think it's powerful when there's collaboration as a value in the schools, where we can partner with outside organizations and specialists to come and share that load, to be those aunties, those uncles, that extended village so that teachers aren't feeling like they single-handedly have to figure it all out," Upchurch said.