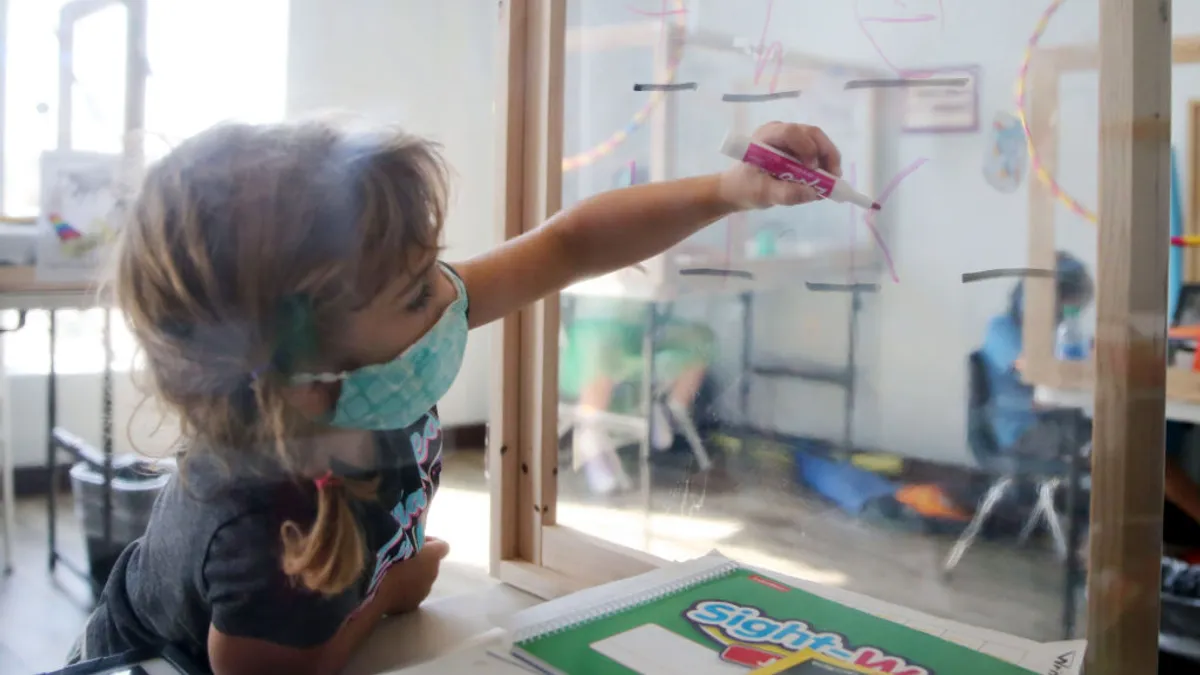

Schools are experiencing increasingly disruptive behaviors despite having various evidence-based practices to prevent and mitigate unruly student behaviors.

So what's going wrong?

That's the question researchers at EAB, a company that provides data-driven insights in education, set out to answer through research, surveys and discussions with education leaders, said Ben Court, senior director of K-12 research at EAB.

Court spoke during a virtual presentation Thursday, cohosted with AASA, The School Superintendents Association, on how district leaders can support schools experiencing disruptive student behaviors by emphasizing why best practices — such as social-emotional learning and positive behavioral interventions and supports — matter.

"Really, what we're seeing is an amplification of many of the challenges that were present in classrooms before the pandemic."

Ben Court

Senior director of K-12 research at EAB

According to an EAB survey conducted last fall of 1,109 teachers, support staff and district and school administrators, 68% of respondents said behavioral disruptions have increased since the 2019-20 school year.

The survey also revealed that observed frequent opposition and emotional disconnect were two of the most common disruptive behaviors from 2018 and 2022, but teachers in 2022 said these behaviors have become more frequent. Every category of measured student behavior increased from 2018 to 2022, including bullying, verbal violence between students, verbal abuse against teachers, and physical violence against teachers and students.

For example, in 2018, 11% of educators observed verbal abuse against teachers. In 2022, the rate doubled to 22%, according to EAB data.

"We're not seeing any new types of behavior, so to speak. Really, what we're seeing is an amplification of many of the challenges that were present in classrooms before the pandemic," Court said. "It's just becoming harder and harder to manage the volume and intensity of those incidents on a day-to-day basis."

And while 50% of district administrators and 55% of school administrators said they had a district-wide behavior management framework or protocols to manage disruptive behaviors, only 36% of teachers said the same.

Teachers, administrators not aligned on behavior practices

"What you have are teachers that feel like they've got a toolbox and listed requirements that they should sometimes adhere to, but not a full sense of the big picture of why those things matter," Court said.

To help educators and school leaders understand the value of positive behavior interventions while still retaining teacher and school autonomy, Court suggested district leaders can drive discussions and actions through these four strategies:

Get everyone on the same page

In the EAB survey, 40% of respondents said district and school administrators have inconsistent messaging on how and when to follow district behavior management strategies.

The disconnect can be repaired from several angles, Court said.

One approach is to focus on the desired outcomes of the program — not just that there's a PBIS program in place. Those desired outcomes can be that students should feel safe, supported, engaged and connected.

A suggested exercise is to have teachers and school leaders map out and align what those practices look like in a school, so there's a common set of practices.

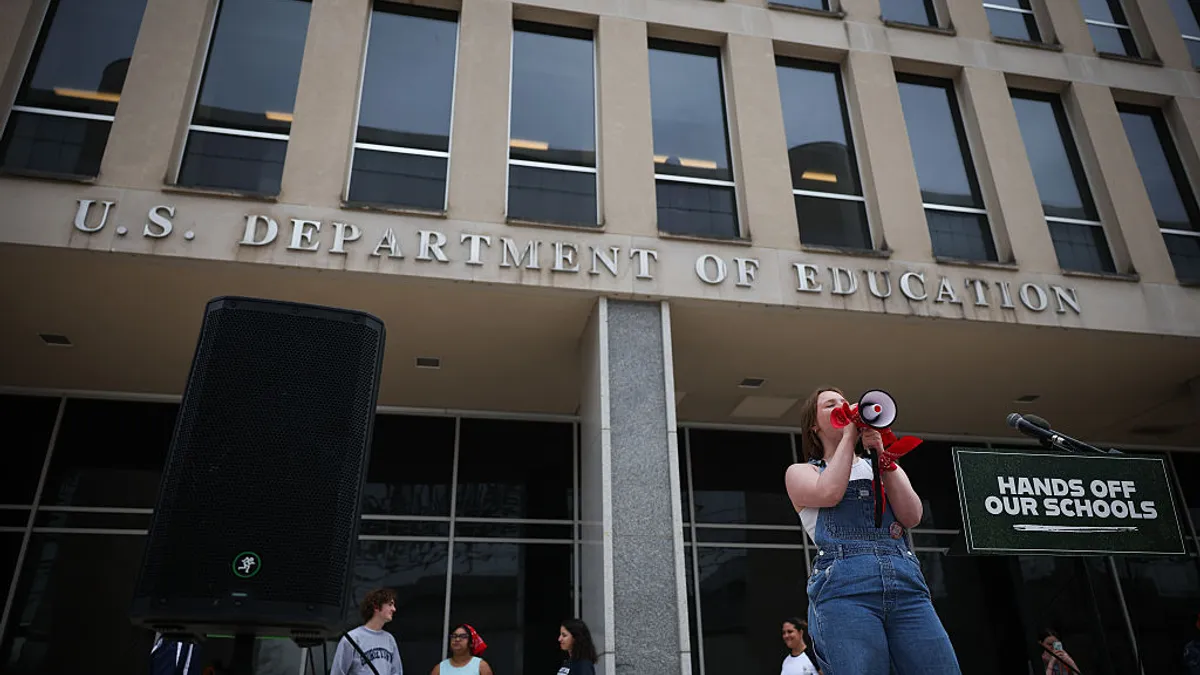

Protect the importance of SEL

Research from several sources shows teachers and administrators feel pressure to prioritize academics over SEL. That is despite the fact that "we do have good evidence from a research perspective that SEL schools truly matter, not just for school today, but in terms of long-term success well beyond graduation," said Court.

To preserve SEL, district leaders can merge academics and SEL conversations through strategic planning exercises to emphasize that social-emotional development is central to academic development, Court suggested.

For high school educators who may feel challenged by this, a helpful approach may be to include student voice in the adoption of SEL practices. According to Court, Greenville County Schools in South Carolina involved students in redesigning its SEL curriculum recently.

Increase training

Being good at behavior management can take a lot of time and work, Court said. It can take 20-100 hours of professional development held over 6-12 months in order to affect teacher practice, according to one estimate shared by EAB.

While SEL training is vital, there are many other educator training options or requirements and only so much time, Court said. Some ways district leaders can help prioritize an educator's SEL understanding is to ask whether there are some mandatory sessions throughout the school year and how to tailor content to educators' specific roles.

More immediate support can be through checklists teachers can use to ensure their classrooms or schools don't have extra stressors due to clutter, poor lighting, excess noise, or lack of water and meals.

Maximize reach of support staff

Nationally, ratios of behavioral support staff — such as counselors, psychologists and social workers — to students are far below ideal. Data shared by EAB suggests there should be one school psychologist for every 500 students, but in 2021, the students-to-psychologists ratio was 1,127:1.

Court said that on this front, district leadership can help create partnerships to secure professionals to work in schools. Those alliances with colleges or local, state and national organizations can start small and grow, even evolving into targeted programs that help recruit staff for specific areas of need in a school, Court said.

Lastly, Court recommends districts analyze their student data to identify the current areas of greatest need for support staff and behavior intervention teams, which will help maximize the work they are doing to support students.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards