Editor’s note: This story is part of a series on the trends that will shape K-12 in 2021. You can find all the articles on our trendline.

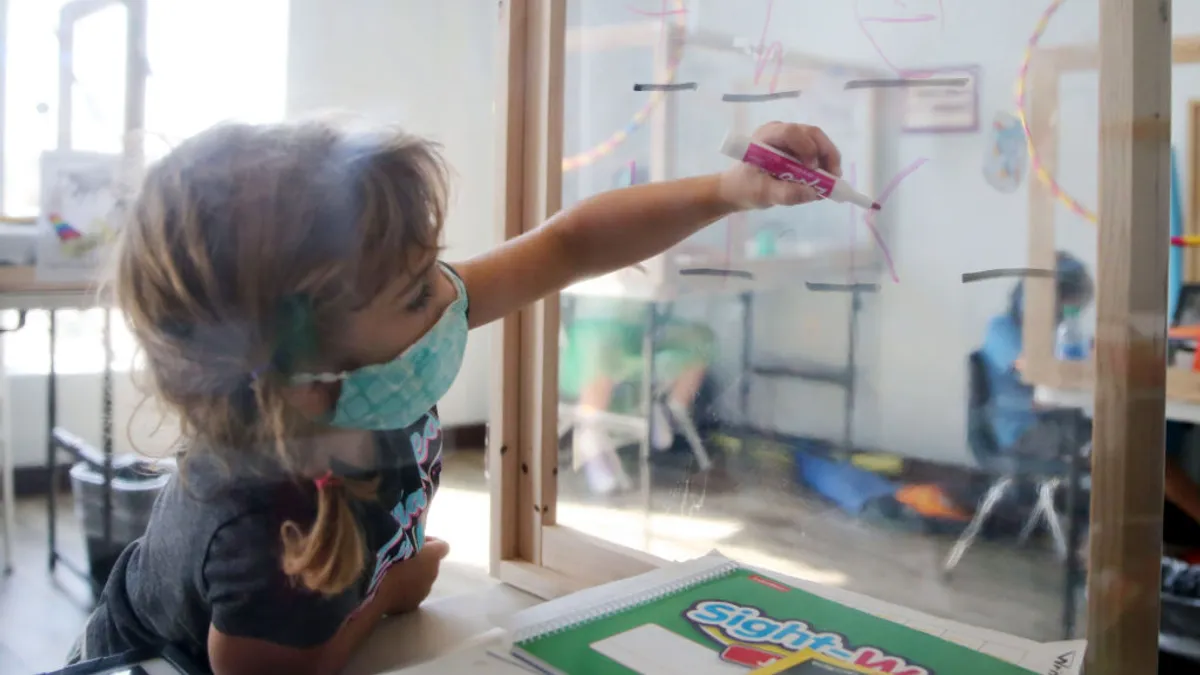

When the coronavirus pandemic hit the U.S. in March, Joliet Public Schools in Illinois went into what Director of Technology and Information Services John Armstrong calls “emergency learning.”

It consisted of “choice boards, paper packets — things that could be done either online or not online,” he said.

That’s since changed. Armstrong said before March, only students in two grade levels had full 1:1 access, meaning each of the students had a device. Now, all of the district's 10,337 students need to have devices to attend school remotely.

In the two months after COVID-19 hit, the nation’s school districts used an average of 1,300 education technology tools each month, according to EdTech Insights research showing just how much districts depend on technology to educate students remotely. That change is unlikely to slow down in 2021

Here are five ed tech trends experts predict will continue making their mark in the new year.

Online learning spurs self-paced learning

While some districts have resumed in-person or hybrid classes, many others are continuing to educate students in a fully remote environment.

“[When] the pandemic ends and we go to whatever normal is supposed to be, I believe that remote learning will continue in some way, shape or form," Armstrong said. "And I think that for the students that benefit from the online remote experience, having the ability to continue to do their schooling that way really provides opportunities that we’ve never even looked at before."

Keith Krueger, CEO of the Consortium for School Networking, said technology has enabled students to have a more personalized learning experience.

“I think that we see ... whether it’s content applications or using learning management systems, that we all don’t have to go through the same printed textbook in a linear way,” he said. “It’s possible with digital content to say, ‘You have to go through this content, but you can do it at your own pace. You can jump ahead to this other module that interests you and then go back to the other ones.’”

That’s something that shouldn’t go away when students return to classrooms, said Liz Lee, director of online learning at the International Society for Technology in Education.

“We still want student agency, we still want choice and voice, we still want collaboration wherever possible, and technology can be a great resource to help us meet those goals,” she said.

Teacher training shifts from 'how to use' approach

Lee also said more teachers have been asking for professional development since going online, which Krueger’s CoSN has identified as a “key enabler” for the evolution of teaching and learning that schools should address in 2021, according to upcoming research.

“We heard from a lot of leaders that their teachers were trying to do whatever they were doing in face-to-face classrooms in an online setting, which doesn’t always work totally well,” Lee said. Now teachers want to learn how to leverage technology to improve learning and not just get by, she said.

Nicholas Svensson, president and CEO of SMART Technologies, creator of the SMART Board, said over time, more tech companies will prioritize integration and pedagogy-driven support, so teacher training is less focused on how to use particular products and more on integrating that technology into the flow of the classroom.

“Educators deserve to have their preferred tools at their fingertips, without having to constantly move students across different platforms and sites,” he said in an email. “Integration has always been a request of schools, but in 2021, I suspect we’ll see more teachers insist that ed tech companies consider their workflow in a more intentional way.”

Data privacy issues become more complex

Mindy Frisbee, senior director of learning partnerships at the International Society for Technology in Education, said her son has come home from school showing off new apps, but it’s unclear what data the apps are collecting and how they know information about him, the user.

“We can’t expect teachers to be privacy lawyers and experts, but they really should understand data practices and what the tools they’re bringing into the classroom are collecting,” she said. “With the shift to online learning, there was a massive movement and now hundreds of thousands of dollars will be spent on new tools faster than ever before. It’s given us an opportunity to leverage what’s happened during COVID. It’s given us an opportunity to really highlight the conversation that’s always there, but it really needs to happen more in depth.”

Svensson said over the last five years, numerous districts and states have been rethinking their data privacy policies, which often means updating outdated policies for current technology.

“But, not all schools — or ed tech companies — have kept pace yet,” he said. “The challenge has been compounded by the fact that students are now learning outside their school and protected school network, creating a new sense of urgency in ensuring the privacy of student data.”

So while this isn’t a new trend, Svensson said, he believes 2021 “will be the year when strong data privacy policies become the norm, not the exception.”

Cybersecurity concerns deepen

While cybsecurity issues aren’t new either, they have become prevalent in the COVID-19 era — from “Zoom bombings” to ransomware attacks.

In September, Las Vegas’ Clark County School District became the largest school district to fall victim to hackers at the time since the pandemic began.

“I feel confident in making a prediction that this is going to be a significant issue for schools — whether they’re online or not,” said Doug Levin, president and founder of EdTech Strategies, founder of the K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center and national director of K-12 Security Information Exchange.

“[School districts have] more users of their systems and devices but because everyone is working remotely, they needed to loosen up controls to let people install software and to remotely support those users, and that creates opportunities for mayhem and mischief,” he said.

Levin said school districts made these changes out of necessity, but now that they’ve had more time to plan, he thinks they’ll be tightening up again — though “there’s always a push and pull between sort of pragmatic and innovative educators who are looking for the best resources for their students and those who are more attuned to privacy and security issues.”

Congress has discussed getting schools more help on cybersecurity issues, but until there’s “political will to solve it,” things could keep getting worse, Levin said.

Connectivity challenges, 'homework gap' persist

Like many other school districts, Fresno Unified School District in California deployed devices for all students learning at home during the pandemic, said Philip Neufeld, the district’s executive officer of information technology. But that isn’t always enough.

Now, the district is working on building a private LTE network to make connectivity available for students without affordable access to high-quality broadband.

A recent Common Sense report shows 30% of U.S. students learning remotely lack adequate internet or devices to sustain effective remote learning.

Neufeld suggests 2021 will likely see more schools start to address the so-called “homework gap,” as COVID-19 has “ripped the Band-aid off the problem of inequitable internet access.”

“There’s no silver bullet here. It’s going to take multiple ways,” he said. “It’s going to take a while to change that equation, and districts are going to have to find ways to do this — and more and more are.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards