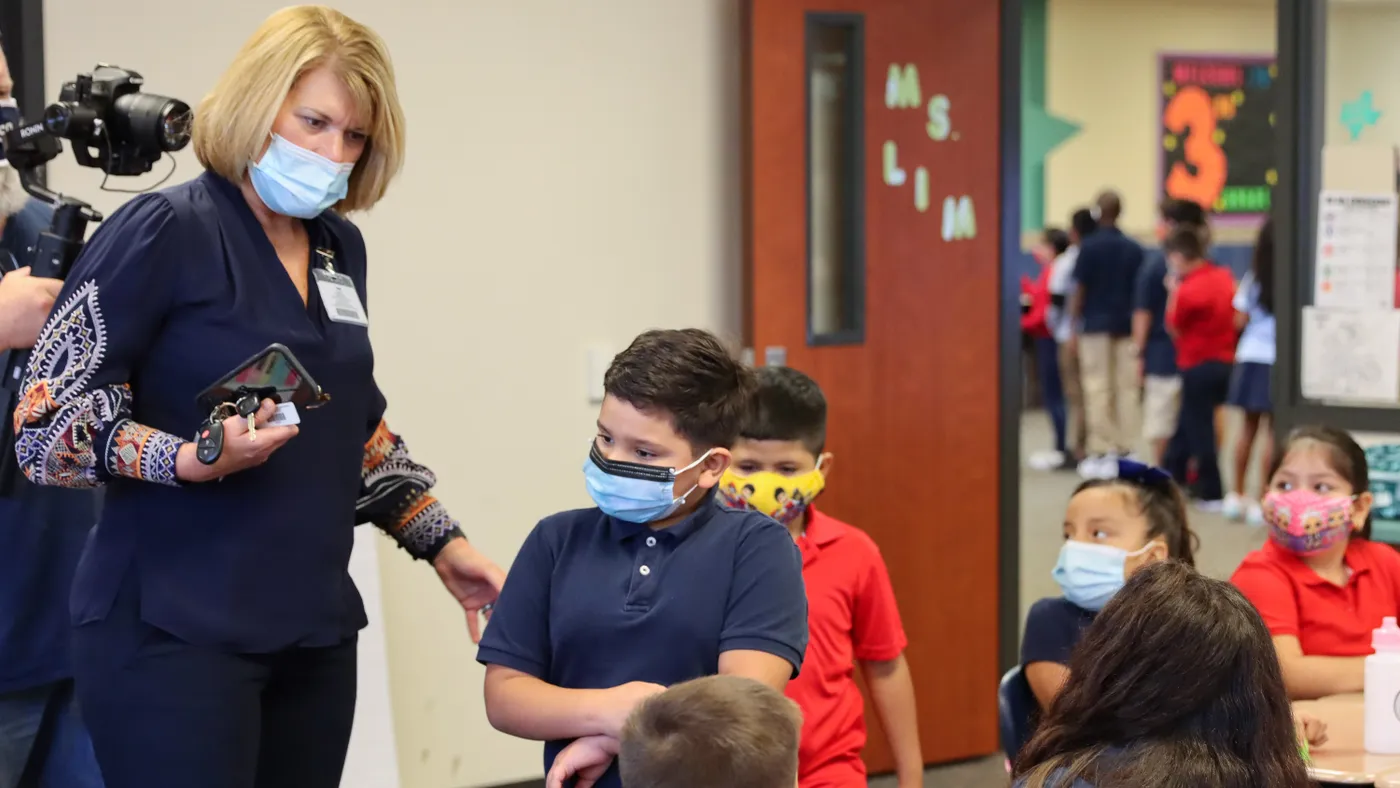

Deciding to reopen schools in the fall of 2020 — during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic — was a controversial decision, but it felt like the right one for Jennifer Blaine, superintendent of Spring Branch Independent School District in Texas.

“If you talk to any superintendent, probably one of the most difficult times in any of our professional careers was trying to deal with this, because it was just unprecedented,” Blaine said.

Spring Branch ISD, though, became one of the first districts in the state to return to in-person learning — and Blaine said that getting students quickly back into the classroom paid off. The district has seen double-digit gains since the 2019-20 school year on every student assessment, and its high school graduation rates are among its highest ever.

The pandemic was a strong reminder that trust, relationships and transparency are crucial for school leaders when it comes to communicating with families and communities, she said.

“There was nothing rosy or cheery about the situation,” Blaine said. That’s why it was important for her to acknowledge to families during COVID that “this is a really hard situation” and that “we’re going to get through this together.”

Spring Branch ISD is one example of how the pandemic that began five years ago this month — and the mass infusion of federal emergency education funds that followed — spurred innovation and encouraged schools to be more nimble in addressing student, staff and parent needs.

By rapidly distributing devices to all students, focusing on school-family communications and expanding summer programs and mental health services, schools reacted in ways that left many positive imprints on school cultures and the business of learning, say education experts.

But five years after March 2020, when the pandemic severely disrupted teaching and learning, some education stakeholders are disappointed that the energy that drove collaborations and innovations has mostly dissipated, and widespread reforms have not taken hold. What's worse, some say, is the return to the status quo of teaching and learning in many localities while academic achievement remains low and chronic absenteeism stays high.

"I don't think we have delivered on what people said they wanted, both educators, and students and families," said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which has monitored the pandemic's impact on schools. "The pandemic was an opportunity for us to assess how to do things differently, and yet, for the most part, I think we snap back to normality," Lake said.

'Kids are struggling right now'

What’s most urgent now is the focus on learning and having high expectations for academic achievement, education experts and families say.

Because of pandemic-induced trauma and disruptions to learning, some say educators' academic expectations of students dropped.

"I can't tell you how many kids are struggling right now," said Keri Rodrigues, founding president of the National Parents Union, a 1.7 million membership organization with more than 1,800 affiliated parent organizations in all 50 states, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. Disappointing academic performances are, in part, because educators eased off high expectations during the pandemic and don't show an urgency to reverse the learning loss, she said.

"I think for some parents, it is soul-crushing to see how schools are giving up on kids because the pandemic happened. I really think that that is the most heartbreaking piece of this."

Educators and researchers have called for urgent action to boost academic performance, particularly for lower-achieving students who lost ground during the pandemic.

Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who has been monitoring the impact of COVID on schools, notes that 40% of 4th graders scored below basic in reading on the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress. "That's really not good. Scoring below basic — you're really way behind," he said.

In addition to pandemic learning loss, chronic absenteeism has been COVID's "indelible" mark on schools, said CRPE's Lake.

According to Malkus, chronic absenteeism is the No. 1 issue in education right now, especially its disproportionate impact on disadvantaged students. Chronic absenteeism is when a student misses 10% or more of school days over a school year — or about 18 days — for any reason, including excused and unexcused absences and suspensions.

During the first year of the pandemic, schools messaged parents that gathering together was dangerous and could spread the virus — and while that was true, schools have since mostly lacked communication stressing the importance of school attendance, Malkus said.

"We're having a hard time getting kids to come back regularly," he said. The national chronic absenteeism rate was 28% during the 2022-23 school year, just slightly lower than the 30% recorded the previous school year.

Schools haven’t really had a chance to catch their breath since COVID subsided, said Barbara Hunter, executive director of the National School Public Relations Association.

Once schools reopened, they had to address the post-pandemic learning gap and deal with the big rise in chronic absenteeism rates. Additionally, she said, schools felt the general “seeds of distrust” in public education.

The latter challenge points to the need for school leaders to better communicate their positive stories, Hunter said. “I think one of the best things you can do to build trust and confidence is engaging families in their kids' education, in school events where they can see and feel the good stuff that's going on.”

'Listening and learning'

School-family relationships became vital during the pandemic. As their children accessed virtual math, reading, art and even physical education classes, most parents got to see for the first time just what their children were learning during the school day. Moreover, parents of young students had to be co-teachers in a new and unfamiliar model of online school.

In some ways, that pandemic-era school-parent partnership sparked deeper appreciation for each party’s role in education. Schools got creative in meeting the needs of students and families. New Jersey's KIPP public charter school, for example, held night kindergarten classes so that working parents of K-1 students could support their children during online school.

Connecticut's Manchester High School realized it had a serious problem a year into the pandemic when administrators saw that several dozen students were at risk of not graduating. It seemed they had disconnected from school when COVID-19 shifted everyone into virtual learning mode.

The 1,700-student school took a bold step to create from scratch a summer program with accelerated courses for those students, featuring fun, hands-on activities such as podcasting and cooking. Those efforts eventually evolved into a regular school year credit-building curriculum called Flight Academy that is putting more students on the path to a diploma, said Amanda Navarra, the program's creator and director.

"We kept saying that we wanted to make changes, and we didn't want to snap back to normal," said Navarra. "We see this now. We're not just going to go back, even when schools have everyone back in the building all the time."

Navarra continues to refine the program, which has three staffers, with plans to add more career and college readiness skills and internships and possibly expand to serve more students. "It's a lot of listening and learning and trying to be responsive and trying to not put the operational first, but put the people first," she said.

‘We are still excluded’

But at the same time that districts were working to build relationships with families, fractures inevitably developed. As schools began opening campuses to in-person learning, parents and visitors were often shut out due to safety precautions, some parents say.

And today, five years later, parents for the most part still feel unwelcome at schools, Rodrigues said.

"We have not returned to normal when it comes to welcoming parents back into schools," she said. "It's almost as if those restrictions and the ability of schools to restrict parents from being kind of present in schools and being more deeply integrated just physically into the ecosystem of a school, it's never recovered."

Whether it is parents coming to campuses to read their child's class a book, to have lunch with their child, or to help deescalate their upset child, it "feels like we are still excluded from being in the school environment," Rodrigues said.

Some schools faced greater challenges with distrust in public education during COVID because of already meager district communications, said Vito Borrello, executive director of the National Association for Family, School and Community Engagement.

On top of that, most teachers weren’t trained to engage with families before the pandemic, which exacerbated the problem, he added. If a teacher hasn’t spoken with a student’s family before, it’s more difficult to build trust and communicate with them when something negative happens.

Indeed, public satisfaction with K-12 education in 2023 dipped back to 2000's record low of 36%, according to a Gallup poll. Satisfaction rates had steadily dropped from 50% in 2020, and they have now begun to rebound, hitting 43%, in 2024.

Still, almost 1 in 5 school communicators reported a lack of trust in district communications among families in 2024, NSPRA’s Hunter said.

During COVID-19, public satisfaction in K-12 education reached its lowest point in decades

The parental rights movement, sparked at least partially by COVID, contributed to growing distrust in K-12, Borrello said.

Parents sought more involvement in their children’s education because of the urgent circumstances, Borrello said, and because they had a front-row seat to seeing their children learning from home.

“If there wasn’t good communication or better communication than previously, what parents rights did — or in some cases continues to do — is pit parents versus teachers,” he said.

That movement, often praised by Republicans, has led in recent years to thousands of book bans in schools and libraries, curriculum restrictions, and efforts to combat districts’ diversity, equity and inclusion policies.

Some of that parent pushback escalated at contentious school board meetings and in protests against masks or other pandemic restrictions in front of district buildings.

"When you see parents behaving that way, it's generally because they're deeply worried about their kids," Rodrigues said. What schools should be saying to parents is "Listen, I need you. I want us to have, like, not just transactions with each other. I want us to have a transformational relationship. I don't have anything to hide."

'We are hiding nothing from you’

During COVID, Spring Branch ISD faced claims from parents that teachers were trying to “indoctrinate” students through online learning, Blaine said. When she asked parents for examples, little was forthcoming.

“There was a period where I think parents became very distrustful, but I also think that was a narrative that was spun nationally and kind of layered on top of everybody’s school district,” Blaine said. “I will tell you in Spring Branch, we were not indoctrinating anybody.”

While the school community has moved past that issue, Blaine said, it was a tough time to earn trust. And that's why Blaine found it even more crucial to quickly reopen schools.

“That became super important, because if you're worried about what we’re doing, come in,” Blaine said. “Sign into the front office, make an appointment. We are hiding nothing from you. Come on in, and let’s see what’s going on.”

School transparency should especially be applied to students' academic progress, Rodrigues said. "That's part of how that trust breaks down with parents. Because don't lie to me and tell me that my child is doing fine when I can hear in my living room that he is struggling."

'Careful thought' about ed tech?

Not only did the pandemic fast-track the rush to provide every student with a device so they could learn from home, it also fueled greater use of learning platforms making school assignments, class notes and the status of grades easily accessible online.

Many students and parents found these portals valuable for tracking academic progress — or for seeing what schoolwork was still incomplete.

Increased adoption of video conferencing technology, meanwhile, opened doors for virtual parent-teacher conferences — necessitated by the pandemic — to continue past the health crisis. In addition, the ed tech lets schools broadcast student performances and sporting events, which is especially helpful for parents who can't attend events in-person.

"If the technology is there, why would you not be giving parents every opportunity to engage when they can and how they can?" said Rodrigues.

Virginia’s Louisa County Public Schools, meanwhile, took an innovative turn during the pandemic to help families in the 511-square-mile rural district connect to the internet. There, like in many rural areas, connectivity is a challenge, said Doug Straley, superintendent of the 5,300-student district.

So the district had its career and technical education students and staff build solar-powered Wireless on Wheels units during COVID. They built about 30 units and placed them throughout the county so families could drive up and get connected to high-speed internet.

Some of those units are still in use, Straley said, as the county continues to install fiber internet infrastructure for the greater community. The project is expected to be completed in one to two years.

K-12's reliance on ed tech has grown stronger since the beginning of the pandemic when some school systems struggled to provide school-issued devices and reliable internet connections.

But in the rush to quickly adopt ed tech, crucial steps were missed, some say.

"I think we've had a long tail of the increased use of devices without necessarily all the training, evolution, careful thought that should go into how and when and for how long those devices are used," said Malkus.

Administrators and teachers should carefully consider the purpose of digital learning tools — and only use them when confident they benefit students. Otherwise, teacher-led instruction is preferable, he said.

"I think that the rapid adoption of so many online tools sort of hopped, skipped and jumped over a lot of that checking," Malkus said.

‘Have to weather the storm’

While school leaders say they are eager to expand on the best practices learned from the pandemic, a slew of changes emanating from the new Trump administration — including the dramatic dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education — is unleashing another wave of uncertainty.

Parents have many questions and concerns about the impact the Education Department changes will have at the local level, according to the National Parents Union. At the same time, some other parent groups are excited about and supportive of the federal push to give parents and schools more decision-making power.

Blaine said she is “very worried” about the fallout, given that Spring Branch ISD has a significant number of students from low-income households. If the Education Department ceases to be, Blaine said, a lot of questions remain about what would happen to the federal Title I funds that benefit high-poverty districts such as hers.

But if COVID has taught Blaine anything, she said, it is that “this too shall pass.”

“So much has happened in six years that has never happened before. We’ve got COVID. We have all of the indoctrination accusations,” Blaine said, and now there are threats of federal funding being pulled.

"We just have to weather the storm and instead of getting super worked up about it, for me, I’m going to advocate for my kids and I’m going to hold us all accountable.”

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed photo support to this story.