It’s “sacred time” at Jefferson Elementary School in California’s Hawthorne School District (HSD) — a time of day when Principal Josh Godin visits classrooms to observe instruction. Lately, he’s directing his attention more toward what the students are doing during lessons, not what the teachers are delivering.

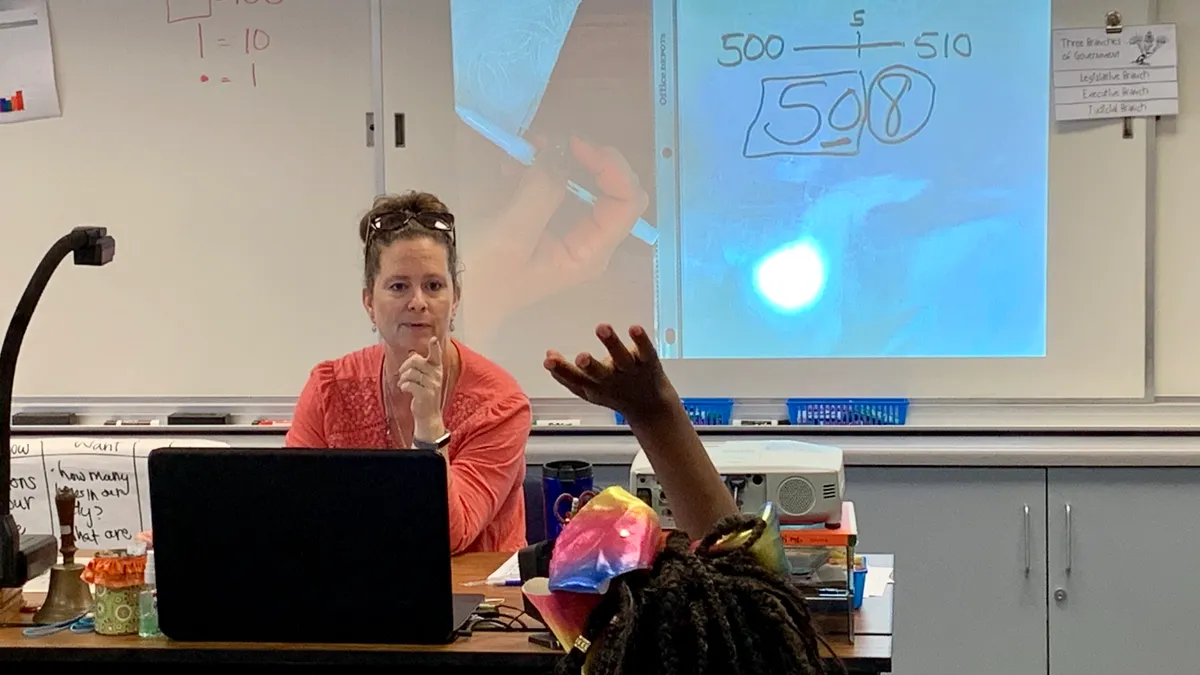

“You want to see their energy,” he said. In Sandra Martinez's 2nd grade class, students are discussing hurricanes and identifying consonant digraphs "th" and "wh" in the text. In 3rd grade, teacher Stefanni Gonzalez gives students practice on how to use a number line to find the closest 10.

When he leaves classrooms, Godin sends short emails to teachers from his iPad about what they’re doing well or where they might need support.

When he first became principal, he had no assistant principal and was responsible for planning professional development, handling student discipline issues and managing all the other issues that arise at a school, such as cars parked in bus loading zones.

Now, David Rosato, the school’s dean of students — who interacts with students on the playground during recess — focuses on school climate and handling any behavior issues that arise.

“It frees me up to do a lot more,” Godin said.

Protecting the time for school leaders to spend in classrooms by hiring deans at all of the district’s schools is one of the policies keeping HSD above state averages in key areas tracked on the California School Dashboard, including academics, chronic absenteeism and suspension rates.

“We are the district that should not be performing the way we are performing,” said Helen Morgan, who has served as superintendent for 10 years and is beginning her 38th year in the 8,000-student district.

East of the Los Angeles area’s South Bay — with about 90% of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch and 31% as English learners — HSD is one of seven California districts profiled in a new report from the Learning Policy Institute (LPI).

Focusing on “positive outlier districts,” the report highlights those districts in which black, Latino and white students are earning higher-than-predicted English language arts and math scores on state assessments, after taking socioeconomic status into consideration.

The authors focus on the role that districts play in contributing to increases in student achievement, noting that “districts offer the potential for scaling up change from schools to systems in a sustainable way, rather than engaging in isolated efforts that transform educational practice one school at a time.”

The report also puts these districts in the broader context of the shifts California has made since adopting the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) in 2012. The new finance system places additional responsibilities on districts to focus on the educational needs of students in low-income families, English learners and students in foster care.

“California districts had a unique opportunity to respond effectively, and some have done better than expected in providing deeper learning opportunities to all students,” the authors write.

Developing the ‘expertise of educators’

Jefferson students wear many variations on the districtwide uniform of “a solid color collared shirt with a twill fabric bottom.” It’s a policy that the district implemented three years ago, based on the practice used at Hawthorne Math and Science Academy, a high-performing "dependent" charter school created by the district.

“We want our kids to matriculate to Hawthorne Math and Science,” Morgan said. The district’s three middle schools each feature a different academy program, allowing students to focus on fine arts, STEM or business. All schools also have a full-time math and literacy coach.

But enrollment has been declining in recent years, with families no longer able to afford housing in a community where a new stadium is being built for the Los Angeles Rams. Fear of immigration raids has also had an impact on enrollment and parents' participation in school, but Morgan said those concerns have subsided.

Other districts featured in the report are the Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD), Education Dive’s 2017 District of the Year, and the Chula Vista Elementary School District (CVESD), near San Diego, as well as Clovis Unified in the Central Valley, Gridley Unified in the upper Sacramento Valley, Sanger Unified, near Fresno, and the San Diego Unified School District.

LBUSD, the report said, works closely with university partners Long Beach City College and California State University Long Beach to create pathways for students into postsecondary education and to prepare teachers and school leaders.

In his 2016 case study on the district, education reform researcher Michael Fullan said the district has developed “the expertise of educators to make good decisions” and that leaders “built systems of supports for all educators across the system in order to enact their vision in all Long Beach classrooms.”

In CVESD — the largest elementary school district in the state — dual-language programs have been a central strategy for narrowing achievement gaps between English learners and students with English as their first language. “Chula Vista took a slow, deliberate approach to the [Common Core State Standards], building knowledge and awareness of the standards prior to full implementation, according to the LPI report.

The authors provide a few common lessons from the outliers, including having a clear districtwide vision while at the same time “delegating considerable responsibility to school sites for how to enact that vision." These districts have also “avoided the worst of California’s severe teacher shortages” and have hired “relatively few" underprepared teachers, they write. “They were regarded as attractive places to work, largely due to positive working environments and support for teaching.”

Morgan also attributes the district’s positive growth to its strong relationship with the teachers and classified personnel unions — a relationship strong enough that when the LCFF increased funding to districts, they didn’t argue with HSD’s decision to put money toward the dean positions.

“They understood we needed to use the money for support for students,” she said.