Educators Jeanne Spiller and Karen Power formed a friendship over their love for hockey and their common experiences as school leaders.

Spiller, an assistant superintendent for teaching and learning in the Kildeer Countryside School District 96, north of Chicago, and Power, an education leadership coach and former school and district leader in New Brunswick, Canada, also shared similar views on the demands that often pull principals in multiple directions and divert their attention away from focusing on instruction.

“No matter how intentional you want to be, the demands of people happen on a daily basis,” Spiller told a room full of school and district leaders last week at Learning Forward’s annual conference, held in St. Louis.

As much as principals want to focus on what is going to “shift achievement” in a school, the unexpected issues that arise and the concerns of staff members, parents and students can derail an administrator’s carefully planned schedule because they want to help solve problems.

“That’s the trap I fell into as a new leader,” Spiller said. “I wanted to have an open-door policy. I got myself in a place where I never did anything that I thought was important because I was trying to be responsive.”

As Spiller and Power continued to reflect on their experiences coaching other principals, they came up with eight areas of focus for being a more intentional school leader. And they thought it was a sign when they realized Power’s favorite hockey player is the Washington Capitals’ Alex Ovechkin, number 8, and Spiller’s favorite is Patrick Kane, who wears 88 for the Chicago Blackhawks.

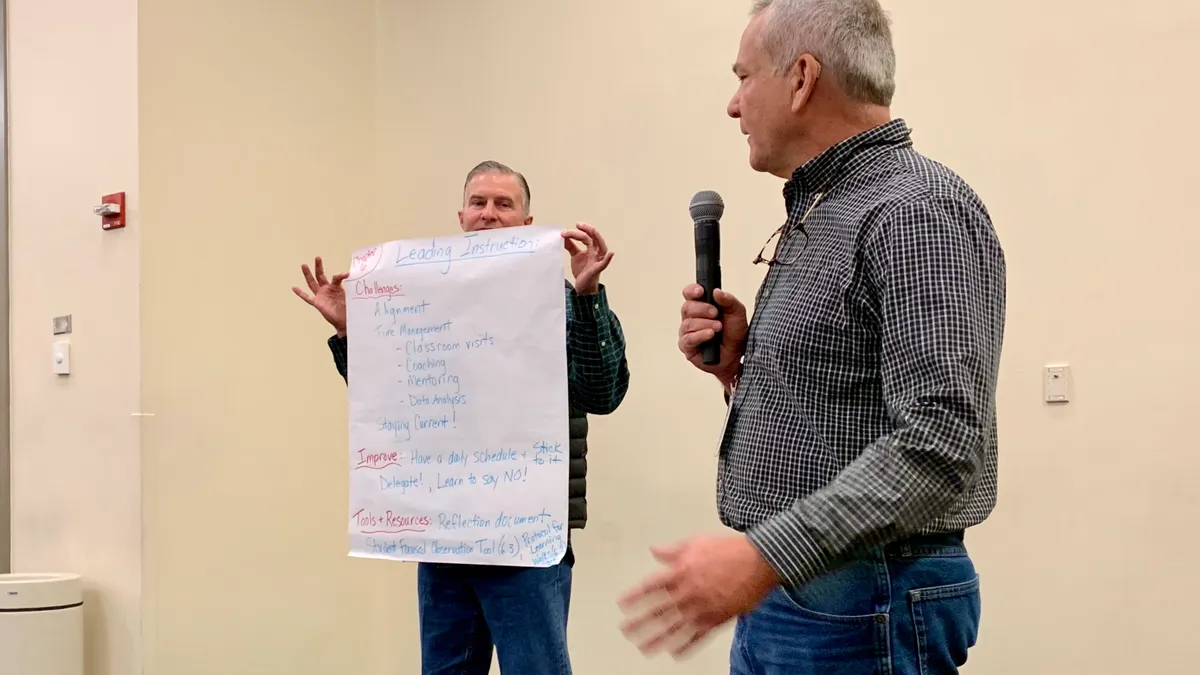

In a roundtable working session, Spiller and Power led participants through identifying the challenges and solutions related to those eight areas of being an intentional leader.

Intentionality

One participant who worked with others at his table on this topic suggested identifying “sacred time” related to visiting classrooms or working with teachers so staff members will know interruptions are discouraged.

Spiller added school leaders need to frequently communicate their priorities so teachers and parents understand why they might be unavailable. “We need to clarify our priorities much more often than we think we do,” she said.

But she also added if a principal tells a teacher who just pops into the office they will meet during planning time — and the principal doesn’t follow through — trust can be broken. Furthermore, she suggested principals take time at the end of each week to identify the issues or tasks that distracted them from how they planned to spend their time.

Organization

Participants who brainstormed this topic said a lack of clear roles and responsibilities, as well as staff turnover within a school, can contribute to a climate that feels more chaotic than organized. And Spiller said having routines that make students feel welcome and that they belong can also contribute to a more organized environment.

Throughout the session, the presenters also provided suggestions for what principals can do in eight minutes, days or weeks to see progress in each area. For example, a school leader could take eight minutes to either walk through the building and identify ways to improve safety or organization or spend that time in one classroom focusing on structure and classroom management.

Shared leadership

For some school leaders, delegating responsibilities to other administrators or teacher leaders is still a shift from what they experienced.

“Some of us worked in the days where we worked by ourselves,” Power told the group. “We did not collaborate in the ‘80s. I remember being asked what chapter I was on in the textbook, and that was about as close as I got to collaboration.”

Participants said it’s important to make expectations as specific as possible when assigning authority to other staff members, and Power said school leaders also need to be intentional about who they choose for their leadership team.

Evidence-based decision-making

One group of leaders shared helping educators confront any biases they may have regarding students is a step toward being able to make decisions based on evidence. Another group working on the same topic suggested teachers need time to examine data and school leaders can model how they analyze data and make sure they have the tools they need.

Having “data days,” Power suggested, is one way educators can be intentional about the protocol they will use for making decisions based on the data.

“Don’t think you’re going to impact every piece of data every year,” Power added, noting it’s important to pick a few areas of focus.

Prioritizing the students

One participant addressing the group said because teachers are most in touch with students, administrators “have to think about how we are supporting teachers.” Others talked about having fewer schoolwide initiatives so teachers can concentrate on their students’ needs.

And Spiller said principals can practice scenarios with members of their leadership teams to understand how to make decisions that are best for students.

Leading instruction

Related to the overall theme of being intentional, being an instructional leader, participants said, takes time management and staying current on research and policy issues.

“Often our teachers know more about what’s going on out there than we do,” one school leader said.

They suggested setting aside time to visit classrooms and having a “coaching and mentoring” approach toward teachers. One school leader from Texas said his district has a room for professional learning communities on every campus and posts students’ photos in those spaces to draw attention back to what they are trying to accomplish.

Communication

Attendees talked about generation gaps and the fact a message can be misconstrued or misinterpreted by staff members depending on the mode of communication used. They said it’s important to think about the best format in which to deliver the message as well as the content.

Spiller emphasized the importance of listening to teachers, parents and others in the school community.

“Communication starts there,” she said, adding if she’s “thinking about how can I solve your problem for you,” then she’s not really listening.

Community and relationships

Challenges the participants said they face include having parents who have had negative experiences with schools in the past, as well as parents who think “they are entitled to your time.” Another challenge exists for administrators who lead schools that draw from multiple communities.

They suggested that how secretaries welcome and respond to parents and other visitors to the school can be a key factor in creating a sense of community. Parent academies, coffee talks with the principal, and using social media were other suggestions for creating connections with parents and community members.

One participant shared that her school holds parent-teacher conferences after church services to make the meetings more convenient.

While another tip Spiller shared was not part of the eight, she emphasized leaders need to carry their efforts to be intentional when they choose what conferences they attend. Otherwise, they might leave with great ideas, try to implement them as soon as they get back to their schools, and ultimately shift away from the goals they were trying to reach.

“I’m very intentional about what I choose to go to,” she said, “to get better about what we’re already doing.”