The roiling immigration controversy is knocking on the schoolhouse door, as a House education subcommittee this week heard testimony on whether children who have entered the country illegally — accompanied and sometimes unaccompanied — are overwhelming public schools.

Tuesday's hearing came on the same day that the Biden administration announced that it is temporarily closing the United States’ southern border to unlawful asylum seekers who the White House said have "overwhelmed" border patrol agents and the immigration system.

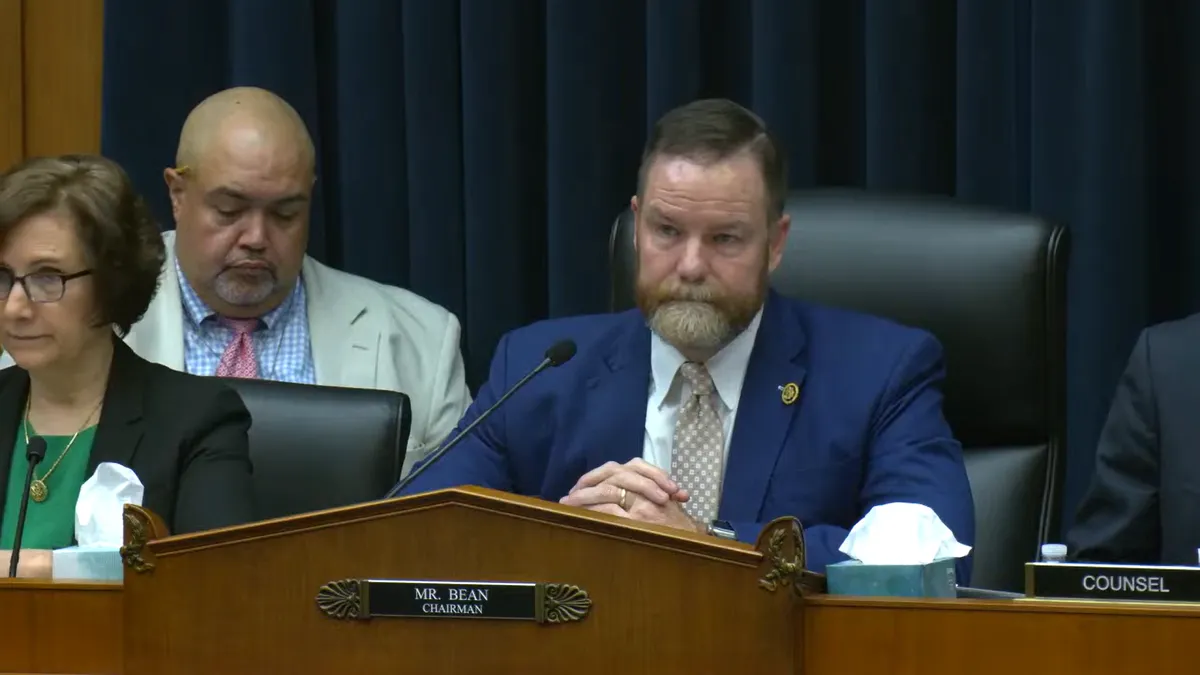

"K-12 schools — the subject of today’s hearing — are often the first to feel the impact of our open border," said Rep. Aaron Bean, R-Fla., chairman of the Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education Subcommittee. The U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1982 ruling in Plyler v. Doe required public schools to educate children regardless of their immigration status.

In the years since Plyler, Bean said, "tens of millions" of immigrants have illegally crossed the border, "with countless filtering into the school system."

While it is difficult to get a complete picture of the number of K-12 children without permanent legal status, about 6 million children under age 18 lived with at least one undocumented family member, according to 2021 data from the American Immigration Council.

This past May, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported 9,943 unaccompanied children unlawfully in the country, a 13% decrease from the month prior.

If every undocumented child encountered by border patrol entered the school system, it would cost the country over $2 billion a year, according to Bean.

Educating these children "requires substantial resources, altering the learning environment for all students," said Bean.

Education experts at the hearing reported the impact of immigration policies on public schools, including:

- Increased enrollments, particularly in preschools.

- Bus delays due to the influx of newcomer children.

- Increased costs to provide ESL, translation and other resources.

- Low parental involvement because those in the country illegally may fear law enforcement involvement and also may face language barriers.

However, lawmakers and witnesses disagreed on whether the solution was allocating additional resources for K-12 schools or changing immigration policy.

"This is not something that can be solved with more money," said Danyela Egorov, vice president of New York City's Community Education Council 2, a council established by the state Legislature to ensure public school parents have a voice in community school district decision making.

Rather, Egorov and other witnesses testified that it was a question of misallocating existing resources to serve children who are in the country illegally.

"Our first priority must be the safety and education of our students, and no amount of funding can paper over these complex challenges that threaten to overwhelm our schools," added Mari Barke, a trustee on California's Orange County Board of Education.

However, Amalia Chamorro, director of the Education Policy Project at UnidosUS, disagreed, saying the problem is chronically underfunded schools. "The challenges today are symptoms of a broken education system," she said. "The responsibility lies with Congress, not our schools, to fix this."

For fiscal year 2024, House Republicans put forth an education appropriations proposal that would have entirely slashed the budget for Title III, which funds language instruction for English learners and immigrant students. They also proposed cutting Title I funding — which supports many schools attended by immigrant children — by 80%.

Whether undocumented children add to or subtract from school culture was also a point of contention. Chamorro argued that immigrant children in general bring resilience, grit and motivation to succeed — contributing to a positive school environment with traits that are valued in the workforce.

Yet others called this group a drain on instruction time and teacher bandwidth.

"It does drag down the entire classroom," said Barke.

But Rep. Jahana Hayes, a Democrat who was a public school teacher for over 15 years in Connecticut, urged Barke and others to consider that both American and immigrant children should be able to learn.

"It's not one or the other," she said.