Dive Brief:

-

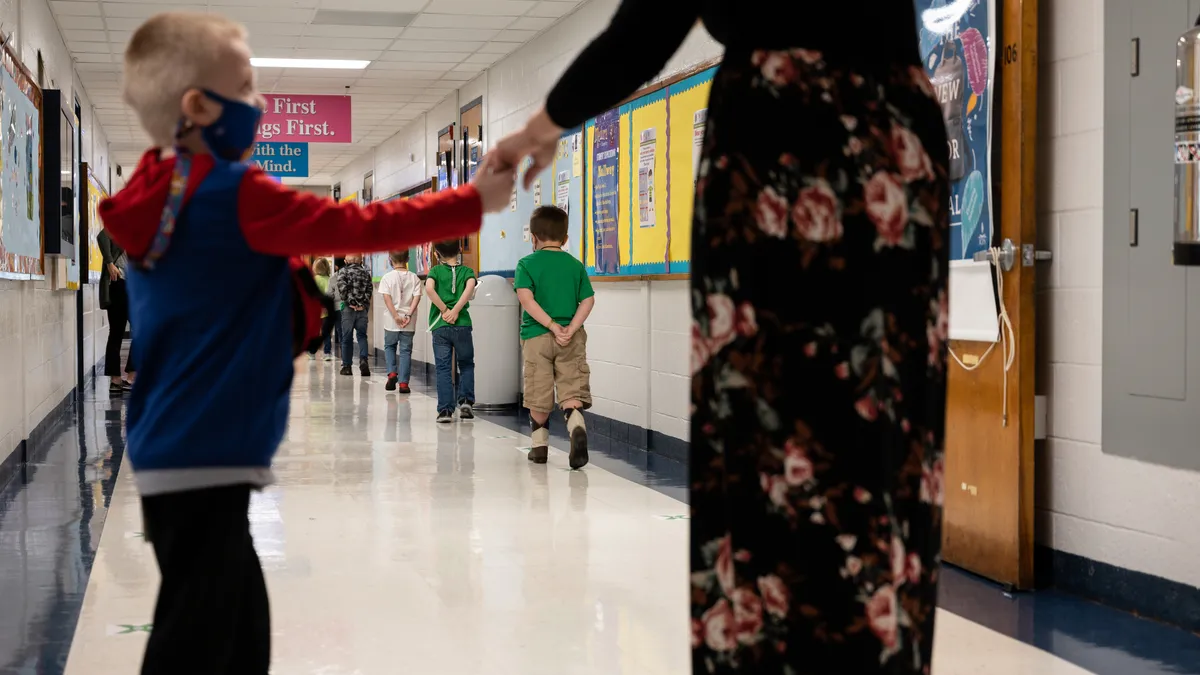

While there's evidence and recognition that students' mental health has worsened over the past few years, the pandemic cannot hold all the blame. Other risk factors, such as systemic racism, anti-gay bias, harmful behaviors related to social media, and other stressors may also carry some of the fault, according to a new report by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

-

These complicated and varied influences on youth can make solutions seem unattainable, and there's a lack of "dynamic and collaborative efforts" to find those solutions, the report said. The report did find "greater willingness" among educators to partner with caregivers and parents to support children's social, emotional and mental health.

-

Other promising practices noted in the report include purposeful efforts by teachers and administrators to give students agency and greater voice and choice in their learning and development, as well as communitywide coordination in social-emotional learning and behavioral supports.

Dive Insight:

CRPE's report draws on input from a four-person panel of education and youth development experts. It is a follow-up to a 2021 paper that called for schools to invest in mental health supports for students in the aftermath of pandemic-related school closures.

Both reports are part of a series included in The Evidence Project, a CPRE initiative studying the impacts of the pandemic on K-12 and related solutions-based research.

"Helping young people right themselves emotionally will require many individuals, organizations, and agencies to organize around a unified vision of what success looks like for young people and to build the tools to measure progress toward that vision," the latest report said.

The report promotes three systems-level strategies for impactful change:

-

Embrace technology innovations. Although some technology-based efforts did not work well for all students, there are pandemic practices that have longer-lasting potential. Virtual parent-teacher meetings and virtual counseling sessions, for example, can make it easier for parents and teachers to connect and for students to meet with counselors.

Additionally, some asynchronous learning approaches can free up time during the school day for discussions, collaborative work and relationship-building. -

Don't make SEL compete with other efforts. The panel noted other education initiatives, such as positive behavior interventions and anti-bullying efforts, that may seem in competition with SEL as distinct concepts but are really parts of an overarching goal for mental wellness.

Schools should take a holistic approach with these different but aligned efforts rather than other goals. Conversations about these connections could also prevent the politicization of SEL and the narrative that SEL programs take focus off of academics. -

Build and integrate data systems. Fragmented or incomplete data systems on youth well-being can contribute to less efficiencies in response to concerns and making connections with factors influencing students' mental health.

In making changes to data systems, school and community leaders can ask, “Who is best positioned to design and manage a community-wide data system for youth well-being and development?” Other questions to ask include: What measures need to be tracked, and what barriers need to be overcome to enable policymakers to develop and administer these measures?