Dive Brief:

- Massachusetts teachers with emergency licenses performed just as effectively as other newly hired teachers in the state during the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent study by Boston University’s Wheelock Educational Policy Center suggests.

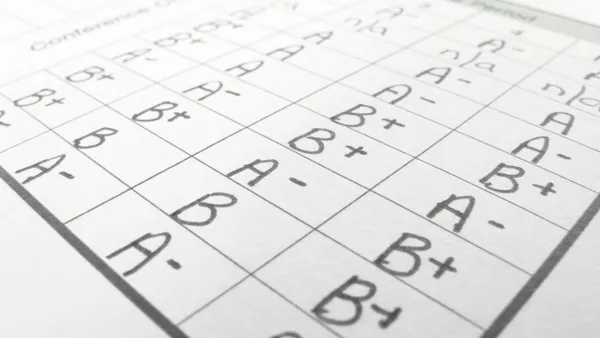

- The policy, adopted to help fill teacher vacancies, did not put students taught by emergency licensed teachers at a disadvantage, according to the findings, which were based on a hiring principal survey, teacher performance ratings and Massachusetts standardized assessment results. The study, however, notes that these findings are “of limited conclusiveness” because the sample sizes are small.

- The majority — 91% — of 1,327 emergency licensed teachers surveyed during the 2022-23 school year said they’d like to continue teaching in Massachusetts public schools the following year. However, the study calls for more licensure flexibility and supports for emergency licensed teachers to sustain staffing needs throughout the state.

Dive Insight:

More research and data are necessary for conclusive evidence on emergency licensed teacher performance, said Olivia Chi, one of the study’s co-authors and an assistant professor at Boston University. But this study does suggest that temporarily loosening teaching requirements did not harm Massachusetts students during the pandemic, Chi said.

“In some ways, I think it is very hopeful,” Chi said. “Given the circumstances, I think students were served as well as we think that they could have been.”

Massachusetts began to authorize emergency teaching licenses in June 2020 to avoid a pandemic-induced teacher shortage. Additionally, COVID significantly disrupted entry into the profession, when licensure testing centers closed and when teacher candidates could no longer student teach in schools.

To qualify for a Massachusetts emergency teaching license, individuals must have a bachelor’s degree, and they must complete traditional certification requirements once the emergency license ends.

The state stopped offering new emergency licenses as of Nov. 8, but those who currently hold emergency licenses may temporarily extend them for one more year or so depending on their teaching subject and when they first obtained their licensure.

Massachusetts’ emergency licensed teachers came from a variety of pathways, said Ariel Tichnor-Wagner, co-author of the study and program director of educational policy studies at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development.

Paraprofessionals made up a notable portion of the state’s emergency licensed teachers, in addition to former private school teachers, out-of-state licensed teachers who recently moved to Massachusetts and career-switchers, Tichnor-Wagner said.

As of June 2023, the study found just over a third of the first cohort of Massachusetts' emergency licensed teachers earned an initial or provisional license, while less than a quarter of emergency licensed teachers from the second cohort did the same.

Based on the study’s findings, Tichnor-Wagner said one of the biggest barriers for those with emergency licenses to obtain a provisional or initial license is finding the time to complete the necessary requirements.

Since 2021, there are an estimated 270,000 underqualified teachers nationwide who have not met their state’s requirements to instruct in their current position, according to a multi-institutional research project on teacher shortages that included experts from schools including Kansas State University and the University of Pittsburgh.

While Chi doesn’t believe all barriers to licensure should be removed, she said there should be some room for flexibility — especially considering the Boston University study’s finding that Massachusetts’ pandemic-era emergency licensed teachers performed well.

There are unanswered questions “about the barriers to entry into the teacher labor market,” Chi said. “This suggests to me, at least, that it may be time to think more about flexibility … in terms of having teacher candidates meet the requirements to become licensed teachers.”

Emergency licensed teachers also responded in surveys and focus groups that they often didn’t know the next steps to obtaining initial or provisional licensure, Tichnor-Wagner said. For instance, some weren’t aware of existing resources to help these teachers offset costs for state tests and study materials.

“I’m hopeful in the sense that this study has opened up, one, what supports teachers might need. We know that there’s a need and we know that there are some resources out there,” Tichnor-Wagner said. “How can local education agencies help match teachers with some of the resources that are there? And then, how can the state provide additional resources to really support these educators?”

The Boston University study was conducted in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.