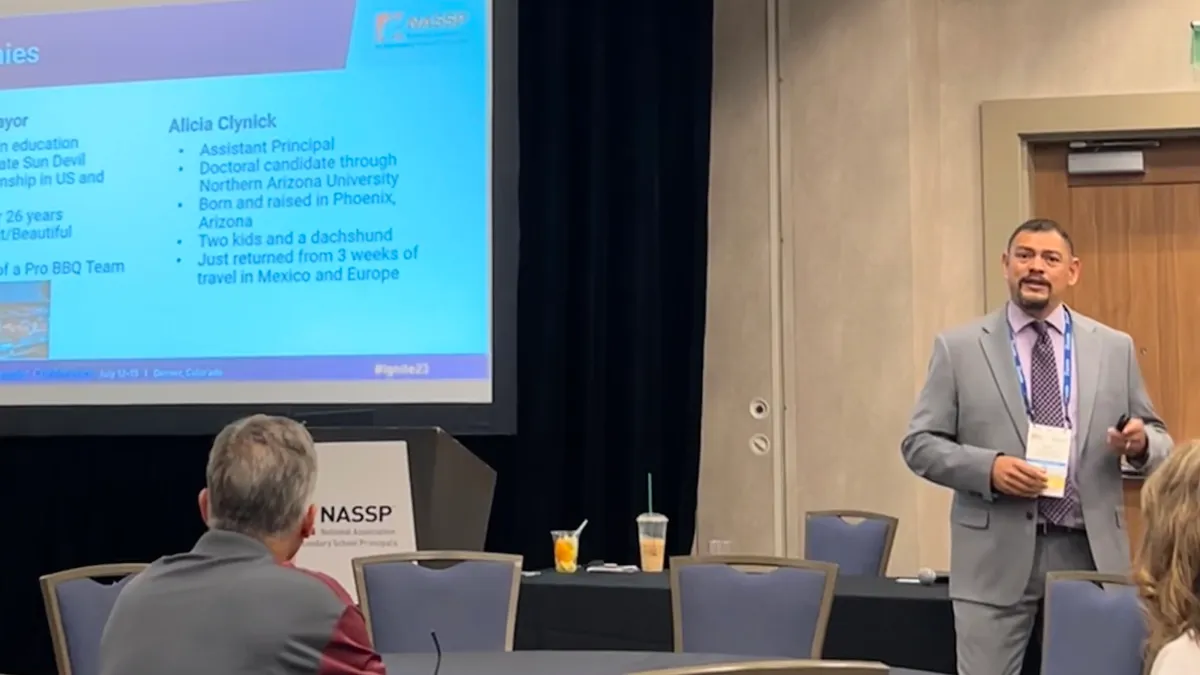

DENVER — Before Kevin Sotomayor and Alicia Clynick began leading Isaac Middle School in Phoenix, Ariz., the Title I school was on the verge of a state takeover.

If the school’s fate fell into the hands of the state, every staff member would have been fired and would have had to reapply for their jobs.

But just as Sotomayor began to take the reins as Isaac Middle School’s principal in the 2019-20 school year, the COVID-19 pandemic struck in March 2020. “If it wasn’t for COVID, the school would have been taken over by the state,” Sotomayor added.

Before Sotomayor stepped in, Isaac Middle School, which has nearly 600 students in grades 6-8, struggled to retain a school principal. Students' math and reading proficiencies were at or below 10%, and teacher retention consistently fell below 50%, said Clynick, the school’s assistant principal.

Administrators also struggled to foster trust with both students and staff as isolation and cliques grew into the school culture. At the same time, students faced high discipline rates involving fights, drug searches and graffiti, Clynick said. Students even tried to set fire to a school field — twice — before Sotomayor and Clynick arrived. Gangs are also prevalent surrounding the school’s community, they said.

There “was a lot of chaos that we were living in, and it was tough,” Sotomayor said, but “amid the chaos, there is also opportunity.”

Three years have passed under their leadership, and now Isaac Middle School has grown from an “F” rating by the state to being just one-point shy of a “B” grade, Clynick said. This all happened amid the pandemic disruption that often left schools in a worse position than before.

The school is continuing to see improvement in reading and math proficiency on benchmark assessments as it creates a pathway toward becoming an arts academy. There are lower discipline rates across all grades, too, Clynick said.

Sotomayor and Clynick outlined several key strategies they implemented to lead Isaac Middle School’s transformation during a Thursday presentation at the National Association for Secondary School Principals’ Ignite 2023 Conference in Denver, Colorado.

Acknowledge what’s wrong

To pull a school out of a failing descent, Sotomayor said school leaders and their staff first have to admit the school is not performing well to begin with.

“You have to acknowledge where you’re at,” Sotomayor said. “First meeting, I acknowledged it to the whole staff. I said, ‘This is what we’re going to do right now, everybody you’re going to repeat after me — we are an F school.’”

There was initial silence in the room, but once they verbally admitted the school was failing, Sotomayor said he could see the staff cringing. Then Sotomayor told them they weren’t going to stop acknowledging this fact until it changes.

After that exercise, Sotomayor said he wanted his staff to set their sights on moving the school forward.

Find your school values

The next step was to establish common values for the school to rally behind. To do that, Sotomayor and Clynick encouraged staff to try an activity where they individually identify their top five personal and professional values.

From there, the school staff collaborated for days to come up with five collective values for the entire school to pursue. Eventually they arrived at: unity, loyalty, perseverance, integrity and dedication. These values are shared everywhere and anywhere throughout the school and students’ classroom lessons, Clynick said, and they grew very familiar with these ideals.

It’s also important to identify how these established values will shape the impact school leaders and staff envision for the school year, she said.

Staff strategically

Once you establish “your what and your why” when rebuilding a school, Sotomayor said principals need the right people to carry out those newly set values.

In Arizona, Sotomayor said there’s less of a teacher shortage issue, and more of a retention problem. “There’s plenty [of teachers], they just don’t want to be in the buildings anymore, because of the culture and everything else,” he said.

So for Sotomayor, he had to get creative with his staffing strategies to ultimately fulfill his school’s new values. That also meant that he didn’t keep any teacher that walked into the building. In fact, Sotomayor said he let go of about 15 teachers when he believed they weren’t the right fit with Isaac Middle School and its values. He made that call even if it meant he had to work as a substitute teacher for several weeks until a new teacher arrived.

“It’s hard, but you have to stick to your beliefs,” he said.

The school also leveraged federal grants, including COVID-19 pandemic aid from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief fund, to get extra hiring help from organizations that align with the school’s mission, including Teach For America, International TeachAlliance, 1 to 1 Tutoring and Catapult Learning.

Establish systems and communication

Overall, Clynick said, it’s important to encourage staff communication and voice. That’s why she has strategically included them on school committees. The school continues to create opportunities for staff to celebrate each other and their students.

But the one key measure of success that sticks out most to Sotomayor is that students now remember and acknowledge him by his name.

Students told Sotomayor when he first arrived that they didn’t want to remember his name because “nobody stays.” But Sotomayor said acting out his school’s value of “loyalty” has clearly made a big difference.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards