Officials in St. Louis Public Schools were prepared for emergency, worst-case scenarios. They had protocols and procedures to protect staff and students against threats. Their safety and security officers had just conducted intruder drills.

But then the worst case happened. On Oct. 24, a 19-year-old former student with an AR-15 rifle and 600 rounds of ammunition killed a student and a teacher at the district's Central Visual and Performing Arts High School. Four other students were shot and survived, and three additional people were injured while leaving the building. The shooter also died, according to police and the school district.

"My years of experience tell me that you really can't be prepared for something like this," said Lori Willis, the district's deputy superintendent for institutional advancement. "I mean, after all, it is probably the most unimaginable thing there is. You read about it, but until it happens in your district, you just don't know what it's going to take to move through the day."

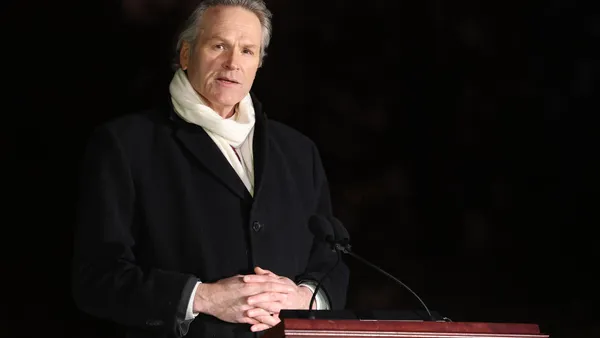

As St. Louis Public Schools officials worked through that day and the days following to help their community recover, they were guided by John McDonald, an expert on post-tragedy school management.

McDonald and his team helped the St. Louis district think through and act on initiatives directly following the shooting, including communicating with the affected school community, as well as with staff, students and families of an attached school and a third school that served as a reunification site for students and parents after the shooting, Willis said.

"They have been able to guide us and to just be a sounding board for some of the things that we weren't quite sure how to move on," Willis said.

McDonald, along with a team of safety and recovery experts, last week launched The Council for School Safety Leadership, a nonprofit organization to help K-12 school administrators lead through crises. CSSL will provide crisis management training and response services focused on the safety of students and staff at public and private K-12 school systems and higher education institutions.

"I mean, after all, it is probably the most unimaginable thing there is. You read about it, but until it happens in your district, you just don't know what it's going to take to move through the day."

Lori Willis

Deputy superintendent for institutional advancement for St. Louis Public Schools

McDonald, co-founder and chief operating officer of the group, said responding to a tragic event — be it a school shooting, a natural disaster or a student death — can be paralyzing for school system leaders as concerns emerge about vulnerability, loss of trust, and potential litigation and legislation . But, he said, these moments should be empowering instead.

"Very few in the school safety space are willing to have the conversation about the uncomfortable truths of tragedy," said McDonald, who worked for 14 years as executive director of school safety for Colorado's Jeffco Public Schools, home to Columbine High School, the site of a 1999 deadly school shooting. "I think we owe it to our parents and our kids and our educators and to ourselves, as school leaders, to have those conversations and be open, honest, and direct and transparent."

Understanding the emotional toll

CSSL, which says it's the only organization dedicated to helping school governance teams prepare for and react to significant school crises, was founded in connection with Missouri School Boards' Association, which operates the Missouri Center for Education Safety.

One of the most important aspects of recovering from a school tragedy is addressing the emotional toll on the community, McDonald said. That includes the often overlooked despair school and district leaders face as they work to address others' needs.

"Tragedy can take an incredible amount of energy and time, and it wears people out and then we see turnover in the aftermath of a tragedy at all levels," McDonald said. "A lot of times our leaders, superintendents, cabinets are really struggling in the aftermath, because not only do they have all the other work with all the other schools, but they have this one school that needs an incredible amount of attention."

He said CSSL's efforts are focused on assisting districts to recover, refocus, and return to their core mission.

"I think we owe it to our parents and our kids and our educators and to ourselves, as school leaders, to have those conversations and be open, honest, and direct and transparent."

John McDonald

Co-founder and chief operating officer of The Council for School Safety Leadership

The response a district makes in the first 10 days after a tragic event can impact — for good or bad — the next five years. That's because if a district is not communicating about its decisions and is not empathic to individuals' needs, distrust and resentment can follow, McDonald said.

"People want to know the why, and they don't want to hear you say, 'No comment,'" he said. "They don't want to hear you say, 'Our prayers and thoughts are with the families.' They want to hear what you're doing, and they want to hear what happened and what you're going to do to protect their kids in the future."

Some of the CSSL services include crisis management support, communications support, expert witnesses and investigative services.

While the immediate response from a traumatic event is crucial, McDonald said, recovery can take years and even decades. As a case in point, he and others continue to work with former Columbine students and families affected by that shooting 24 years later.

Healing through song and dance

In St. Louis, school and district leaders helped students process the tragedy by asking them how they wanted to honor those who died and those who were grieving. The students asked to coordinate a community concert.

The student-led event was held on Nov. 6, just two weeks after the school shooting. Students have also made trips to the state capital to speak with lawmakers about stricter gun laws.

"We continue to be very receptive to anything they want to share with us on how they and their families are handling the crisis nearly six months out," Willis said.

District leaders are also still processing and reacting to the tragedy. They are currently considering applying for a grant for schools that have experienced shootings. Administrators are already discussing how to support students emotionally when the first anniversary of the shooting occurs this fall.

The district continues to lean on McDonald and others for guidance.

"They teach us resiliency by just telling us of their experiences," Willis said. "It's a day-to-day struggle and will be for quite some time. But we're hoping that with the help of McDonald's team and with our own resources that we're providing a framework for our students and our teachers to build on as we move forward.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards