School districts have just over eight months to spend down a collective $122 billion from the K-12 portion of the American Rescue Plan funds directed to pandemic recovery.

The historic one-time allocation is the third and last infusion of monies known as the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief fund, or ESSER I, II and III. While the total $189.5 billion in ESSER has supported an array of COVID-19 recovery efforts such as school safety supplies, high dosage tutoring and additional reading instructors, many localities may face a fiscal cliff when the funds expire on Sept. 30.

In guidance issued last week by the U.S. Department of Education, the department reiterated that districts and states have a path to extend ARP spending for 18 months past the Sept. 30 obligation deadline. It is recommended those requests be made before Dec. 31 of this year and, if granted, spending for ARP funds could extend through March 28, 2026.

And though some districts are still assessing their needs and getting state agency approval for remaining monies, here are three school systems that have dedicated every dime they were given — all while, their leaders say, averting what could be harmful consequences of funding cliffs.

White Plains Public Schools, White Plains, New York

Of the $9.8 million in ARP funds received by the 6,700-student district, all but a portion reserved for capital construction projects has been spent. It's expected that the rest will be used by the spring when new ventilation and filtration systems have been tested, said Ann Vaccaro-Teich, assistant superintendent for business and operations.

About 70% of the money went to replacing HVAC units in a majority of the district's schools. The district also used some of its ESSER II money for this project. Using some other district funds, this effort means all the schools now have central air conditioning for the first time.

With the upgrades, multiple schools can now open for summer programming, and buildings can keep windows closed when it's hot outside or if there's wildfire smoke in the community, she said.

The district was able to move quickly to spend the one-time funds because the community had already identified the HVAC work as a need prior to the pandemic, Vaccaro-Teich said.

In fact, district staff were preparing to present a phased-in HVAC upgrade approach to the school board right before March 2020, she said. That was put on hold as White Plains — and other districts nationwide — transitioned to virtual settings and then back to in-person learning.

But when Congress approved the ARP funding in 2021, it was "a no-brainer," Vaccaro-Teich said.

In addition, the district had a full-time grant writer who helped the school system in tapping into COVID public assistance funds through the Federal Emergency Management Agency. And another benefit was a dedicated state-level employee available to answer the district's questions about ESSER spending, Vaccaro-Teich said.

The district still has a portion of $2 million it had dedicated for addressing learning loss that it plans to spend by the end of this summer. That money will be targeted toward summer programming, extended learning and professional development, Vaccaro-Teich said.

White Plains doesn't anticipate a fiscal cliff after this year, because it did not use any ESSER monies to create new positions.

"It's one-time-only funding and that's the way you have to look at these things," said Vaccaro-Teich. "You never want to build something into a grant that's not a recurring grant, because it can go away."

Williamsfield Schools, Williamsfield, Illinois

When the pandemic hit this rural, one-school district, the immediate priority was to get all 300 pre-K-12 students back to in-person learning as soon as possible.

As those efforts began, staff noticed many students were being identified as physically close contacts from riding the school bus, according to Superintendent Tim Farquer. That meant they had to stay home when another student came down with COVID, increasing educators' concerns that the absences would lead to learning gaps for these students.

So as ESSER money became available, the district combined some of that with funds from the Environmental Protection Agency's Clean School Bus rebate program to replace all seven diesel buses with electric ones. This allowed students to both be more spaced out on buses and to spend a shorter time on bus trips.

Of the district's $462,531 ESSER III funding, about 85% went to pupil transportation services, according to the Illinois ESSER Spending Dashboard. The district also invested in creating a STEM lab and renovating its chemistry classroom, among other initiatives, Farquer said.

Because finding skilled personnel is difficult and would be hard to maintain after the one-time federal funding, the district avoided spending on staffing, he said.

Farquer said investing in electric buses will save the district money on fuel. It is also having a positive impact on attendance. Prior to the pandemic, the district had noted an increase in student asthma cases. The electric buses keep students and drivers from breathing fuel emissions, he said.

The district's ability to use the funds to decrease school absences "was a really strategic investment," Farquer said.

According to the state spending dashboard and Farquer, the district has spent 100% of its ESSER III allocation.

"We did not want to sit on money that could have a positive impact on our kids and community," he said. "We wanted to put that money to work."

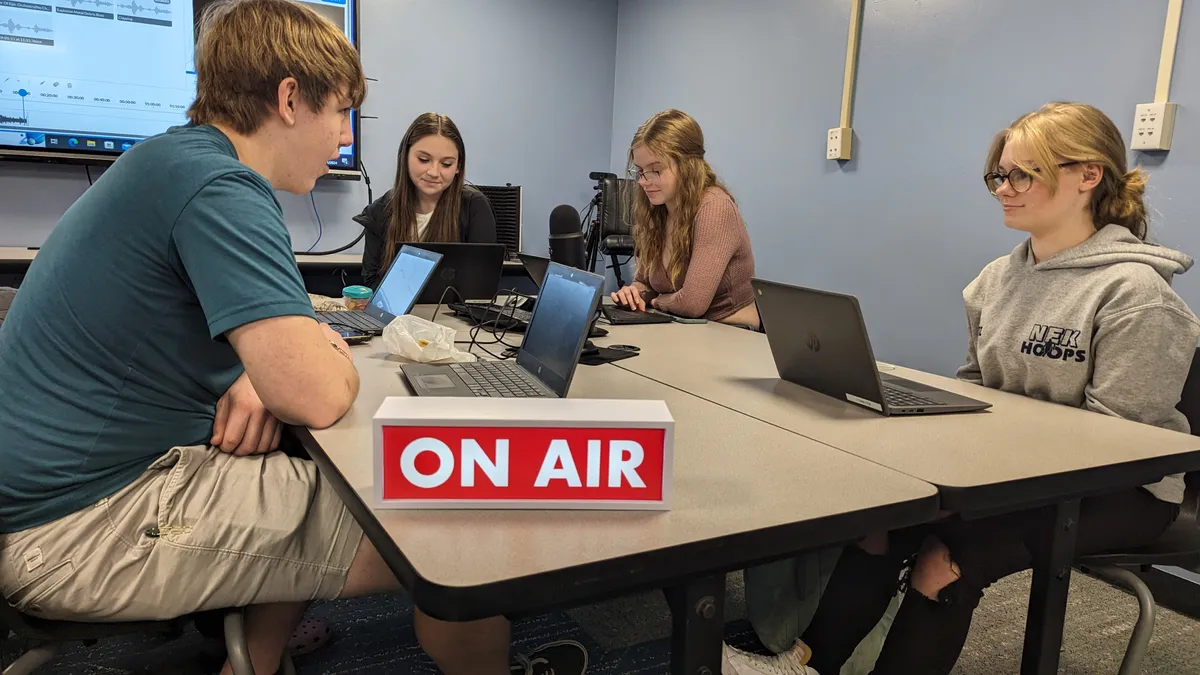

North Country Union High School, Newport, Vermont

Principal Christopher Young said he was fortunate that, as a school leader, he had autonomy to dedicate ESSER funds in the way that was best for his 700-student grade 9-12 school. For North Country Union High School, that meant adding staff in various positions.

A social worker and counselor joined the school's alternative education program. The school also added a physical education and health position, as well as interventionists in about four subject areas to help chronically absent students catch up.

Most of the school's $2.1 million allocation went toward the additional personnel to support students, Young said.

All of that money is committed through the end of ESSER, but Young said he's not worried about a fiscal cliff. A change to the state's education funding formula is providing low-income areas, such as Newport, with more per-student funding. "We've benefited tremendously, and so there was no cliff for us between the end of ESSER and the beginning of the new weighting system."

Additionally, after the ESSER-supported staff came on board, several positions opened up, and the new hires were able to transition into the open positions, which were funded through the school's general budget, he said.

Young noted that many of the new staff members did not come from traditional teacher prep programs, which he said was "eye opening" for him. As a result, the school has implemented new teacher supports and professional development.

For veteran teachers, the school developed "an action research model" to allow veteran teachers to explore areas of interest in their fields. For example, the school's band teacher is studying whether including nonstudent community members in school performances would benefit students.

"My big takeaway [from ESSER] was around how we approach teacher induction and retention," Young said.