While weighing concerns about testing during what is expected to be a stressful time, a number of organizations and agencies say assessments should continue for the 2020-21 school year. Assessing students early, they say, will provide school leaders and teachers with the data they need to help students make up lost ground and move ahead with new material.

Despite pushes in some states for assessment waivers, Jim Blew, an assistant secretary for planning, evaluation and policy development at the U.S. Department of Education, suggested in July states should have no such expectation for this school year.

The National Assessment Governing Board (NAGB) also announced in late July it will continue preparation to administer the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a nationally representative assessment of student progress in reading, math, science and writing for grades 4 and 8.

While the NAGB is still determining how feasible it is to administer the test this school year, Haley Barbour, the chairman of the organization and former governor of Mississippi, said the data from the large-scale assessment would provide "invaluable" information on student achievement that can inform policy, research and resource allocation.

But many educators and others question whether the test should take place this year, preferring diagnostic assessments that are low-stakes and can inform curriculum planning.

What should assessments include?

“The decision to go forward with NAEP has to be taken into context of [the Trump] administration that is pushing hard for schools to be in-person," said Scott Marion, executive director of the Center for Assessment. He instead suggests assessments this year should be "close to the curriculum," or tied to the first few units students will encounter in the fall.

Curriculum experts, including Marion, recommend schools implement targeted diagnostic assessments with a narrow purpose: to get a better understanding of where students are in their learning and what interventions might be necessary to accelerate their pace.

"The value in having data that are curriculum agnostic [is that it] allows us to say, 'Where are the places that we need to spend more time? Where are the kids that need more supports than others?'" said Nate Jensen, director of the Center for School and Student Progress at NWEA.

Jensen hopes districts will disentangle assessments this year from the secondary or tertiary purposes of the data, like informing teacher evaluations, to lessen the stakes of the results.

When should assessments be given?

With districts focusing on rebuilding relationships and providing access to online learning, a first round of assessments will likely be given a few weeks into the school year. Marion, though, strongly urges refraining from assessing students for at least the first two weeks.

Jacquelyn Johnson, director of research, evaluation, assessment and accountability for Clayton County Public Schools, said her district pushed its assessment window and extended it and won't be administering student assessments until after Labor Day. The Georgia district began its school year this week.

And while fall assessments should determine how kids were impacted by closures and give an idea of their baseline, as well as identify their most immediate academic needs, Jensen said winter and spring follow-up assessments should be given to determine if the interventions are improving achievement and growth.

How will curriculum planning be impacted?

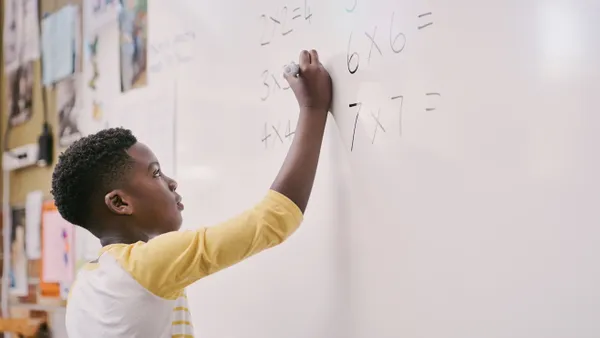

Curriculum experts agree assessments this school year should be used to identify and fill gaps in student learning. When students' gaps are identified, they say, it's important to accelerate their learning rather than to try to gain all the ground lost during closures.

"We need to expose them to grade-level content and curriculum and keep them moving," said Johnson. "If you lower the expectation and remediate a full year because you think they're that behind, there are ways to work smarter than that."

Marion said one way is to pair assessment data with "opportunity to learn data," which includes information gathered from surveys and questionnaires around access, engagement and attendance during closures. “It’s the only way you’ll be able to make sense of the [diagnostic] results," Marion said.

However, there still exists a divide among experts on how to approach the assessment process overall — should instructors enter the school year planning for gaps and allow assessment results to confirm their hunches, or should teachers hope for the best and then let assessments guide curriculum planning?

Marion leans toward the former. "You have to start teaching right away and then worry about the assessment," he said, adding assessments should be used to confirm expected gaps.

Johnson, however, said that attitude could "create angst" for students and teachers. While she acknowledges the research around "COVID slide," Johnson said she doesn't "want our students [and teachers] to feel defeated before they even start."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards