April Callen is a communications strategist, cultural critic and advisor on equity who has helped nonprofit organizations and other sectors develop deeper understanding of equity across race, gender and class, and how to best apply it to their work. Jenni Kotting is communications strategist for the Partnership for the Future of Learning and works with school administrator associations on anti-racist messaging and storytelling.

“The insidiousness of white supremacy is that it turns empirical statements into ideological ones.” — Clint Smith

From Oregon to North Carolina, school leaders around the country are stuck in a difficult position between very distinct perspectives about anti-racist teaching, gender and sexual education, masks and vaccination mandates, and more. Who should have the final say over these matters is under heavy debate.

Across all of these issues, school leaders are working through a false narrative that says “divisive” and “controversial” topics can’t be taught in schools, that biological families alone should have those conversations with children, and that topics like race should be taught with a “balanced perspective,” if they are taught at all.

This is a false equivalency. Just because two perspectives are oppositional does not mean they should carry the same weight. The weight we give a perspective should factor in both empirical evidence and morality.

School leaders are within their role and responsibility to ask plainly: What is the “balanced perspective” when it comes to racial equity?

If a “balanced perspective” is saying that racism doesn’t exist or isn’t something we have to worry about these days, that perspective is not based in reality and shouldn’t be given equal weight in the classroom. Denying the racist nature of historic and current events or insinuating that white students are blamed for institutional racism is empirically untrue.

It is factual, honest, and accurate to say racism does exist and is both observable and experienced in historic and current events.

If the “balanced perspective” is promoting racism or allowing it to be exercised freely through words, actions and symbols in schools through arguments like free speech, it presents a major moral dilemma because it is extremely harmful to students to allow racist speech and symbols space in our schools.

“Divisive” and “controversial” concepts are not purely theoretical or political theater. They inherently relate to people’s identity.

A young person whose biological sex differs from the gender they know to be theirs, a Native American teacher, a young person who is Black, a parent who is white, a staff member who is Latinx, a young person whose sexual orientation is a fundamental part of who they are, people of different religions, languages, and abilities — all of these identities have become politicized and been made to be ideological by actors threatened by progress and unity.

Right now, people’s validity as human beings is being determined by others who don’t live their reality. When adults, from school staff to educators to legislators, try to censor these learnings, young people are cut off from conversations that help make sense of the world around them and how their identities fit into that world.

Having strong feelings about these topics is understandable. Encountering new knowledge can bring up strong personal and emotional responses, and that doesn’t always feel objective. But that doesn’t mean anti-racist education isn’t factual, empirical and necessary to include in school curriculum.

Students are having to be unfairly resilient in the face of both institutional and interpersonal racism — from the disparate impacts of punishment on students of color to obscenely racist and homophobic Snapchat and TikTok trends happening in schools all around the country.

School leaders carry a responsibility for students’ education, safety, growth and development, wellbeing and mental health. And to counter the false narrative percolating around anti-racist and culturally responsive education, we need to be clear about what’s happening at schools and in classrooms.

School leaders can do this by communicating with their communities in a way that invites people to understand anti-racism and equity as pragmatic and empirical instead of political and ideological. Many are doing this by infusing messages with hope and promise — that an equitable and anti-racist approach is the right way to take care of each other.

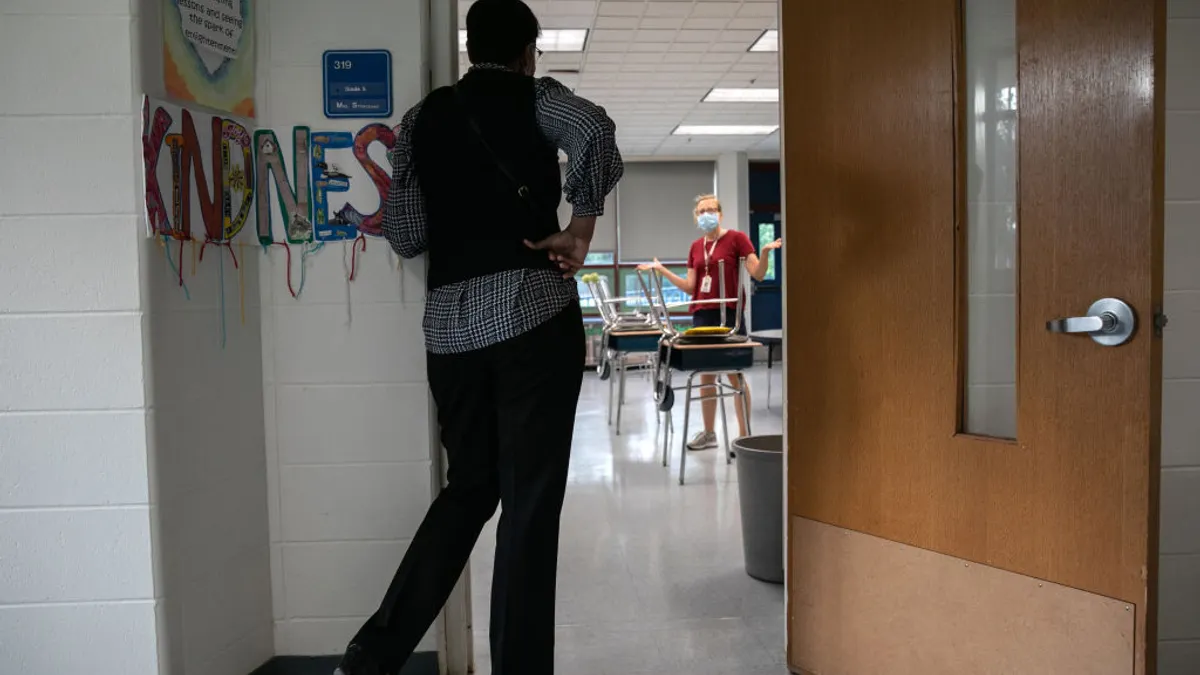

Every school leader we’ve spoken with is taking great lengths to be as transparent as possible about what’s really happening in classrooms to assuage fears that stem from biased national news. Many are having meaningful conversations with parents and community members to reach a point of understanding by being direct and honest about equity values and their district’s plans.

Across the U.S., school leaders want to build trust and strength together. The more school leaders and community members who vocally support honest and real conversations about race, gender and public health, the more successful education will be — to the benefit of the health, well-being, belonging and education of every student.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards