Dive Brief:

-

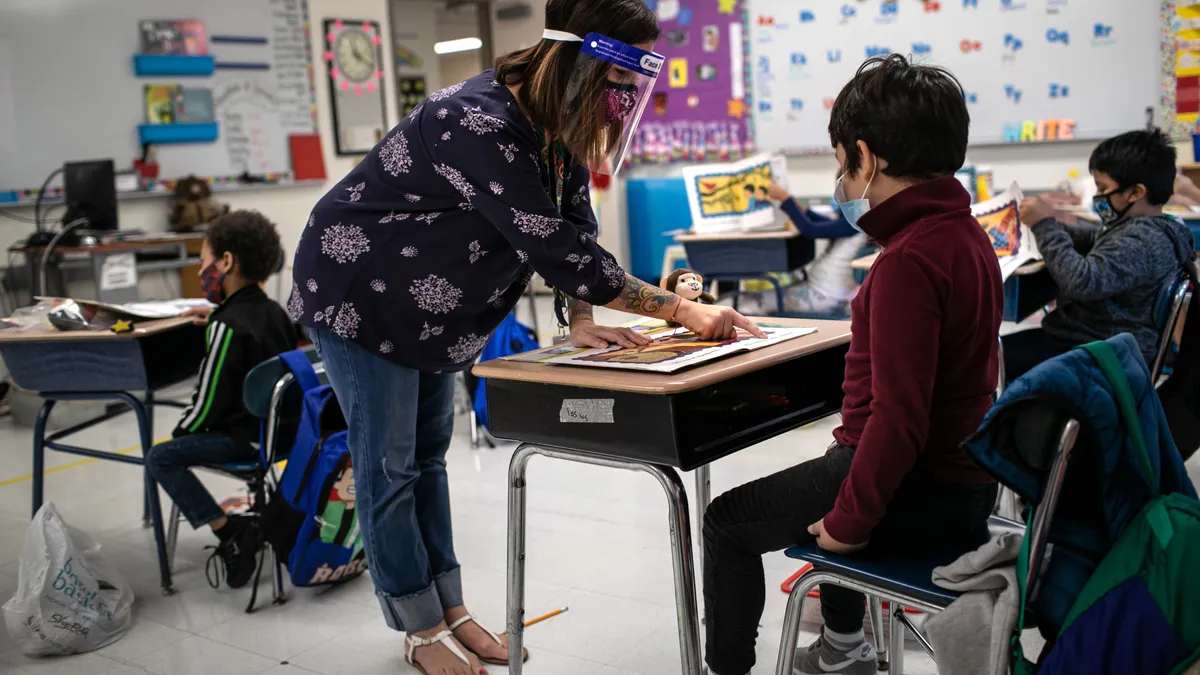

As the pandemic has progressed, so have lags in learning, according to data gathered by NWEA, a research organization that creates K-12 assessments, from over 6 million students in grades 3-8 who took math and reading assessments. Achievement gaps between the highest- and lowest-performing students also widened for the second year in a row.

-

Declines in achievement are steeper for fall 2021 than fall 2020 when compared to fall 2019, the last “normal” measure prior to the pandemic. Scores from fall 2021 were 9 to 11 percentile points lower in math and 3 to 7 percentile points lower in reading when compared to fall 2019, whereas scores from fall 2020 showed a decline of 5 to 10 percentile points in math and relatively typical reading scores when compared to fall 2019 scores.

-

Patterns in declines by subgroup also persist: Black, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native and students in high-poverty schools continue to fare worse than their White, Asian and higher-income counterparts. For example, Black 3rd graders experienced a decline of 10 percentile points in reading between fall 2019 and 2021, while White and Asian 3rd graders experienced drops of only 5 and 3 percentile points respectively.

Dive Insight:

The scores highlight the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student achievement, especially for students from marginalized communities who were already lagging behind their more affluent and White or Asian peers. They also raise questions about the long-term impact of school closures on those subgroups and potential timelines for recovery.

According to a recent report released by McKinsey and Company, a consulting firm that has projected and closely tracked learning lags throughout the pandemic, students in majority-Black schools lag 12 months behind those in majority-White schools. This means the pre-existing achievement gap between Black and White students has increased by about a third.

Inequitable access to academic support could impact recovery times, with higher-income students bouncing back from the pandemic’s effects more quickly than lower-income students, the firm suggests. High-income parents are 21 percentage points more likely to report their child has participated in a program to boost either academic or mental health recovery, including tutoring, summer school, after-school programs, counseling and mentoring.

The report suggests if these disparities continue, students from high-income families could recover unfinished learning by the end of the 2021-22 school year, while historically marginalized students could remain up to a grade level behind.

Lindsay Dworkin, vice president of policy and advocacy at NWEA, confirms recovery times will likely vary across students, schools and districts.

Some kids will be back on track this year, she said.

For example, the highest-achieving students in the top 20th percentile are gaining now, particularly in reading, faster than between 2017 and 2019. Trends are the opposite, however, for the lowest-achieving students.

“It’ll take vastly different amounts of time for different groups of kids to get back on track,” Dworkin said. “For some kids, we’re going to see recovery and then some this year, and for other kids we’re just going to be getting started on what will be a multi-year process of trying to catch up.”

The same goes for districts. “For every single district, the impact is going to look different, which means the road to recovery looks different,” Dworkin said.

For many, learning recovery efforts are just beginning, with districts piloting programs this year and full-scale interventions beginning next year.

Dworkin also emphasized the role of summer programs in keeping students, especially those who experience steep summer slides, on the road to academic recovery.

And while bringing all students back on track will be a multi-year process, with achievement scores often lagging behind intervention investments, other measures like lower chronic absenteeism levels can be good interim indicators that districts are moving in the right direction.

“Don’t despair. We’re just getting started on the whole recovery thing,” Dworkin said. “Hopefully, we’ll see much better progress this year and next year.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards