At Kearsarge Regional Middle School in North Sutton, New Hampshire, Principal Stephen Paterson admits there is a growing fear among teachers around contacting students’ parents.

Some staff members who have taught for decades have particularly noticed less support for public education from parents, Paterson said, and it’s discouraging. When the school needs a family’s support to help a student, parents sometimes accuse the school of causing problems, he said.

“We get blamed, and it can be very challenging for us,” Paterson said. “The politics of the day are that schools are bad.”

In fact, an October Ipsos survey found American public trust in teachers has declined by 6 percentage points since 2019. Overall, teachers are the fourth most trusted profession in the U.S., but public trust in teachers has dipped from 63% in 2019 to 57% in 2021.

The 2021 survey data also reveals Republicans trust teachers less than Democrats, at 56% to 71%.

American public trust in teachers generally dips amid pandemic

Two key factors have led to the decline in the public’s trust in teachers, said Chris Jackson, senior vice president and head of polling at Ipsos.

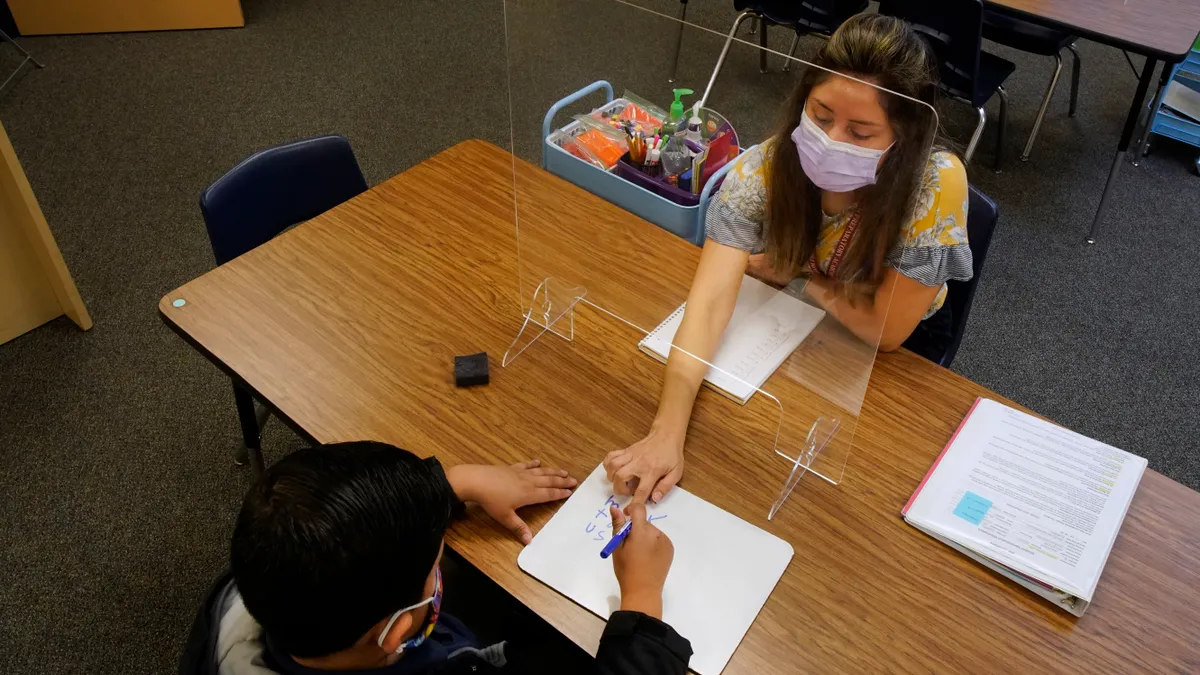

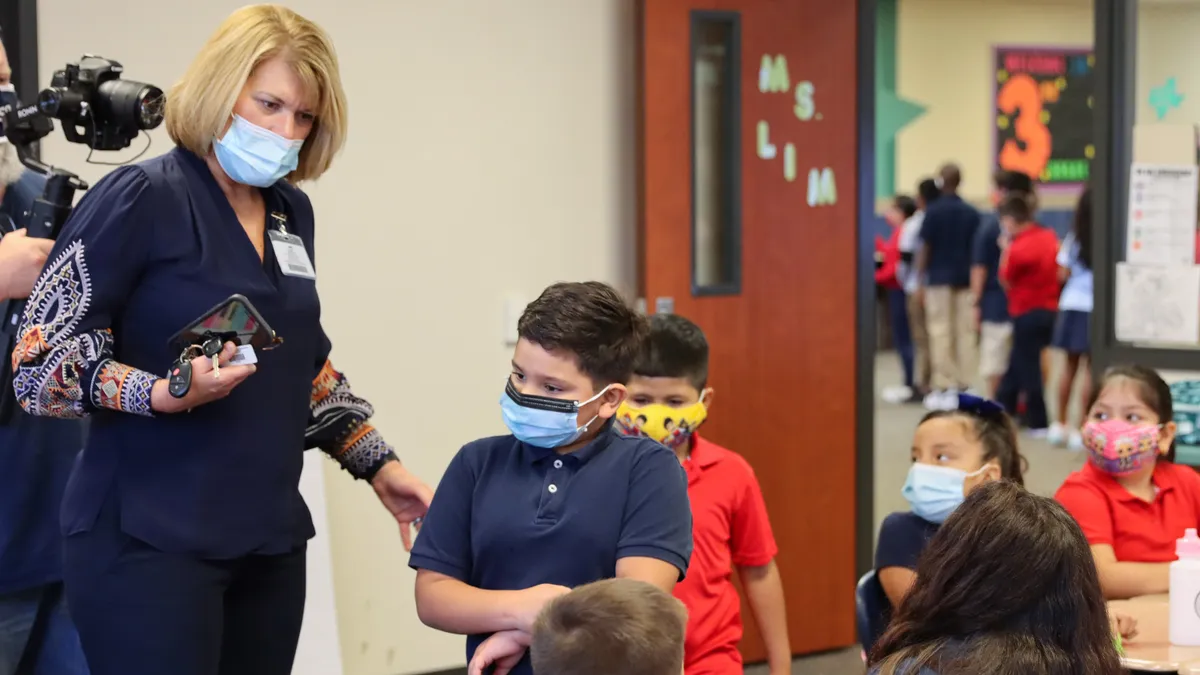

The first is that COVID-19 pandemic protocols in schools surrounding mask and vaccine requirements have turned into a “culture war flashpoint,” he said. And second, political conversations about critical race theory in the classroom have also contributed to growing distrust in teachers.

Jackson noted how Republican activist Christopher Rufo publicly aired his concerns in 2020 about the influence of critical race theory — a university-level academic framework developed in the 1970s that posits America has a history of institutionalized racism and persistent racial inequality — as a way to develop a wedge issue in education and politics.

The term was then picked up in the media and eventually made its way into divisive school board meetings, he said.

“When you get that into the classroom, teachers end up bearing the brunt of it because they’re on the frontlines,” Jackson said.

When a profession is politicized, public trust in the people who work in that sector often declines, Jackson said. “What we’re primarily seeing is a facet of how politics and partisanship has been infiltrated into the classroom. When that happens, basically everybody loses.”

Policies micromanaging teachers emerge

Principals, superintendents and policymakers in some cases react to this growing distrust by micromanaging teachers and implementing more rules and guidelines, Jackson said. While instituting restrictive policies can limit the damage of controversies, it could also restrain innovation and teachers’ freedom in the classroom.

Between January and September of this year, nine “gag order” bills were passed in eight states limiting discussions on gender, race or divisive topics in K-12 schools, sparked by critical race theory debates, according to a report by PEN America, a nonprofit advocating for free expression. Those states include Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

Status of state bills limiting classroom discussions on gender, race or divisive topics, as of Oct. 1

The topic even took center stage during the recent election cycle, with Virginia’s now Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, heavily campaigning that he would combat critical race theory in schools. The Virginia Department of Education has said the academic framework is not included in the commonwealth’s standards of learning, according to WDBJ.

On Nov. 17, Youngkin told the Republican Governors Association annual meeting that his victory in a Democratic-leaning state shows a victory path for Republicans who address education, the Associated Press reported.

On the campaign trail, Youngkin also highlighted a need for increased parental rights over children’s education.

This call for more parental control in education tied to concerns about critical race theory in schools has now reached a national policy level. On Nov. 16, Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri introduced the Parents’ Bill of Rights Act. The bill would give parents the right to sue federally funded schools that do not disclose what their child is being taught.

Schools that consistently violate parental rights outlined by the bill would face “major reductions” in funding, Hawley said in a statement.

As some teachers face mounting policies looking to monitor what they teach, they are also balancing burnout from teaching remote and hybrid classes throughout the pandemic. On top of that, the ongoing teacher shortage is adding additional pressure.

K-12 employees are more likely to report burnout than any other government employee, according to a MissionSquare Research Institute survey of 1,203 state and local government employees conducted in May.

Districts must “lean into this problem”

Schools can’t solve the growing public distrust in teachers by ignoring it, said Rebecca Winthrop, a senior fellow and co-director of the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution.

The debates about reopening schools have likely contributed to the decline in public trust, Winthrop said. A key to addressing that is through establishing valued connections between schools and families.

Educators should not be managing and navigating family engagement on their own, Winthrop added. Teachers carry the bulk of these family relationships, she said, but it’s up to school leadership to allow them the space and time to develop these connections.

In September, Winthrop co-authored a Brookings Institution report outlining a playbook for family-school engagement. The report notes schools with successful family engagement are 10 times more likely to improve student outcomes.

Winthrop has also found districts that spend time building meaningful relationships with their families and communities are less likely to struggle with public distrust. Where there’s already trust and ongoing dialogue, Winthrop said, that can help smooth over the bumps like school mask requirements and other reopening protocols.

“If you don’t have that sort of deep relationship with your families and communities, you will get people who get upset. Certain specific things don’t get heard,” she said.

When schools interact with families, there’s a key difference between involvement and engagement, Winthrop said. Involvement is less effective and typically means a school leads with its mouth but does not listen.

An example of involvement would be a school sending newsletters, sharing information and inviting people into the building to listen. But engaging parents means schools are leading with their ears and inviting parents to the table for an open dialogue with a diverse group of people who reflect the school community, she said.

“The engagement approach is where you really can build these relationships and be in enough of a dialogue and safe space where you can have debates,” Winthrop said.

There’s no quick fix to developing family engagement, but now is an optimal time to begin working on building relationships, Winthrop said.

“You have to lean into this problem. This is not going to go away by raising up higher walls around schools. That’s just going to make people madder,” Winthrop said. “As difficult and trying as it is, … [districts] need to really take stock and think about a bunch of different strategies that they could use.”

Learning from educators who feel trusted

While some schools struggle with family engagement, other teachers are thriving in their community relationships. The key to two teachers’ success echoes Winthrop’s message about building valuable connections with families and students.

In fact, this growing public distrust in teachers does not reflect the reality of Ross Hamilton, a 12th-grade government and civics teacher at Building 21 High School in Philadelphia.

Hamilton credits relationship-building with his students and community for contributing to a strong sense of trust. Daily advisory meetings with students embedded in the framework of his school have helped build those relationships, he said.

“We establish that trust, and once it’s there, it carries on throughout your journey in the school and in the class,” Hamilton said.

Part of the relationship-building in his school also means considering the issues in the local community and beyond that impact his students. Among them, Hamilton said, are students facing gun violence in Philadelphia.

“It has been getting really, really bad out here. And so this is coming in, impacting our community, and it also brings in some trauma that our students are encountering,” Hamilton said.

As a project-based school, Hamilton said he and his colleagues shifted into “change-making mode” to address how students handle these community and national issues.

Over the next couple of months, Hamilton has asked his 12th-grade students to identify a marginalized group on a local, national or global scale. They must then research the issues that have caused these groups to be marginalized and understand how organizations are already working to address these issues.

At the end of the school year, students will create and present action plans to help the marginalized community they studied, Hamilton said.

“This activity is meant to create the next generation of leaders,” Hamilton said. “Also, as they’re working through that, that relationship building is occurring. That trust is occurring because we’re walking them through the process.”

Hamilton said his school leadership has also been supportive of teachers.

Two years ago, the leadership at Building 21 High School also established a committee to address trauma-informed care, restorative practices and cultural competency. Hamilton serves on the committee and said he speaks to staff as issues arise and attends conferences to better understand how to bring the three practices to life within his school.

To build community trust, it’s also important to engage in active citizenship and invite local and state political leaders into classrooms, Hamilton said. So far he has brought in a city council member and a state representative to speak with staff and students.

This is another great way for political leaders to better understand the needs of teachers and schools, including the issues they are facing, he said, which in turn creates an opportunity to find solutions to these problems.

Bringing in culturally responsive teaching

Angela Burley also has solid relationships with her 6th-grade students and their families at Sarah Zumwalt Middle School in Dallas, Texas. Burley cited strong relationships that exist between staff and said she’s connected with parents as well and gives them weekly updates.

Despite the recent overall decline in the public’s trust in educators, Burley emphasized that as a Black teacher instructing in a predominantly Black community, she does not face issues with trust and building relationships because of the cultural understanding she shares with students and parents.

If a teacher can develop a relationship with a parent, then trust will follow, Burley said.

Culturally responsive teaching is a great pathway for teachers to develop relationships with students and parents, and that doesn’t apply to just communities of color, Burley said. Part of culturally responsive teaching is understanding the community’s belief system and behaviors, she said.

“You use that to have open dialogue,” Burley said.

Burley, meanwhile,teaches world cultures in a state where a law took effect Dec. 2 prohibiting teaching certain concepts about race.

The law also prohibits instructional discussions surrounding any “widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.” If teachers do discuss current events, they must do so without political bias, the law states.

Burley believes this law and other policies born out of fears around critical race theory in schools won’t impact her or other teachers in the state. She added that critical race theory isn’t taught in her classroom.

But Burley said she feels 100% safe to hold conversations about race in her school.

“When I teach what I do, I just focus on culturally responsive teaching,” Burley said. “Overt discussions about race where you are purposely addressing issues of race can help bridge gaps we didn’t even know were there."