Dr. Scott Poland is a professor at the College of Psychology and director of the Suicide and Violence Prevention Office at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He is a past president of the National Association of School Psychologists and past prevention division director of the American Association of Suicidology.

Pandemic-related challenges are taking a toll on the nation’s collective mental health, whether through the loss of income, loss of loved ones or loss of community. While no age group is spared, we must pay extra attention to our nation’s teens and young adults, whose mental health needs are the greatest in modern times.

Over the past year, issues of mental health have often fallen by the wayside. Typically when students are physically in schools, teachers can spot signs of self-harm or notice changes in behavior. However, in remote learning, this is often more difficult as students may not be logging online each day, have their cameras off, or not have an opportunity to speak one-on-one with their teacher. Sadly, we’ve seen examples of teen suicide rates increasing since the pandemic, and I fear we may see similar instances in the months and years to come without intervention.

To underscore the direness of the issue, a recent poll from Navigate360 and Zogby Strategies found 55% of 16- and 17-year-olds personally knew someone who had considered self-harm or suicide over the past six months. Additionally, only 37% of students thought their schools were equipped to deal with this problem.

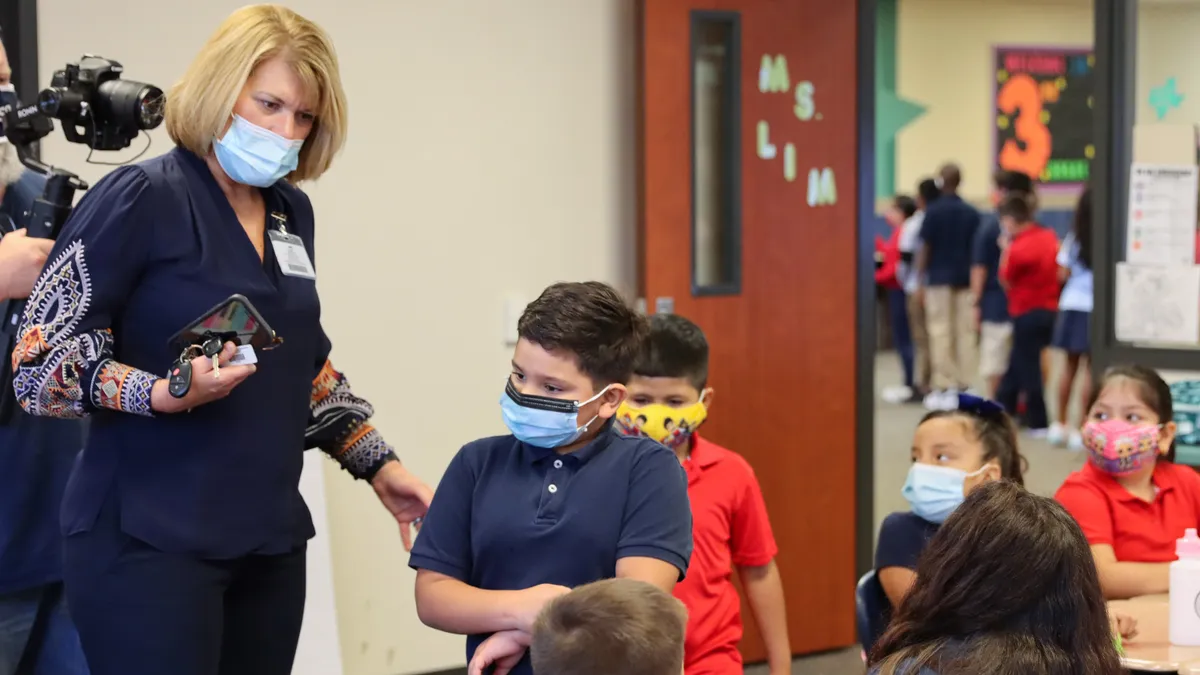

To prevent a “twin-demic” of self-harm and suicide, schools will need to be more proactive in their outreach to students and take steps to improve their students’ mental health and wellbeing. As more schools across the country begin to reopen for in-person learning, it’s critical that schools put equal focus on ensuring students are as mentally healthy as they are physically.

This starts with systemic changes in school culture. Though millions of students may have fallen behind academically, administrators need to refrain from prioritizing academic achievement above all else. Students will need time to process their trauma and experiences of the last year. With more than 500,000 deaths from COVID-19, it’s inevitable students will still be grieving for lost family, friends and neighbors.

A culture of emotional health and safety must be implemented from the top-down and may require superintendents and principals to reorder their priorities. Instead of asking students to solve mathematical equations, homework that centers self-care and emotional wellbeing should take center stage. Writing assignments that allow for student expression can be an incredibly useful way for teachers to get insight into what their students are feeling. Throughout my career, I’ve seen numerous cases where assignments such as these have allowed schools to intervene and prevent students from harming themselves.

Wherever possible, schools should direct some reopening or stimulus funds to hire additional mental health staff. Before the pandemic, school counselors were already a scarce resource. In underserved schools, I’ve heard of instances where the ratio between school counselors and students was 1,000-to-1, more than four times what the American School Counselor Association recommends.

Now, more students than ever will be coping with grief, anxiety, depression, anger, isolation, abuse and homelessness. To ensure students don’t slip through the cracks, schools will need to hire additional counselors so they have time to help address students’ mental health instead of filing paperwork. Even if hiring additional full-time mental health counselors isn’t possible, schools should consider leveraging community resources whenever possible. This could include partnering with community mental health clinics or having some recently retired mental health professionals work part-time.

Lastly, schools must also talk about suicide openly. Many people, including school leadership, teachers, and parents, are uncomfortable with the topic of suicide. I’ve heard from schools and parents who think any mention of suicide or self-harm will give students the idea. However, open conversations around what a student can do to help themselves or help a friend who is considering self-harm or suicide are critical. Mental health professionals must directly ask at-risk students if they are considering suicide. These conversations give a student who has thought about suicide a chance to realize they’re not alone and help is available. By not talking about suicide openly, we are contributing to the stigma and making it harder for students to feel comfortable asking for help.

Despite the slow return to normal enabled by the vaccines, the pandemic’s impact will be long-lasting, especially on teens and young adults who are in a critical phase of their development. As schools reopen, developing a plan to address student mental health and mitigate the risks of suicide and self-harm should be paramount. By placing equal emphasis on physical and mental health, we can ensure schools are safe spaces where students can grow and thrive.