Testing's disruption is inevitable and the space is ripe for it, Andreas Oranje, principal research director at the Educational Testing Service (ETS) told a crowd gathered at SXSWedu 2018 this week. He predicated that, in the next 10 years, assessments and testing would be "inseparably connected" to optimal learning, that having the right data would matter more than ever, and that at least 95% of current ed tech offerings would be gone or obsolete because they don't really provide value as tools.

Perhaps most notably, he pointed out that assessments are approximations, but that the closer they get to the real thing being measured, the less inferential distance there is between a student's abilities and evidence of those abilities.

Essentially: There's more of a direct measurement of a student's ability to perform a given task the more an assessment actually involves that actual activity.

That's where performance assessment comes in.

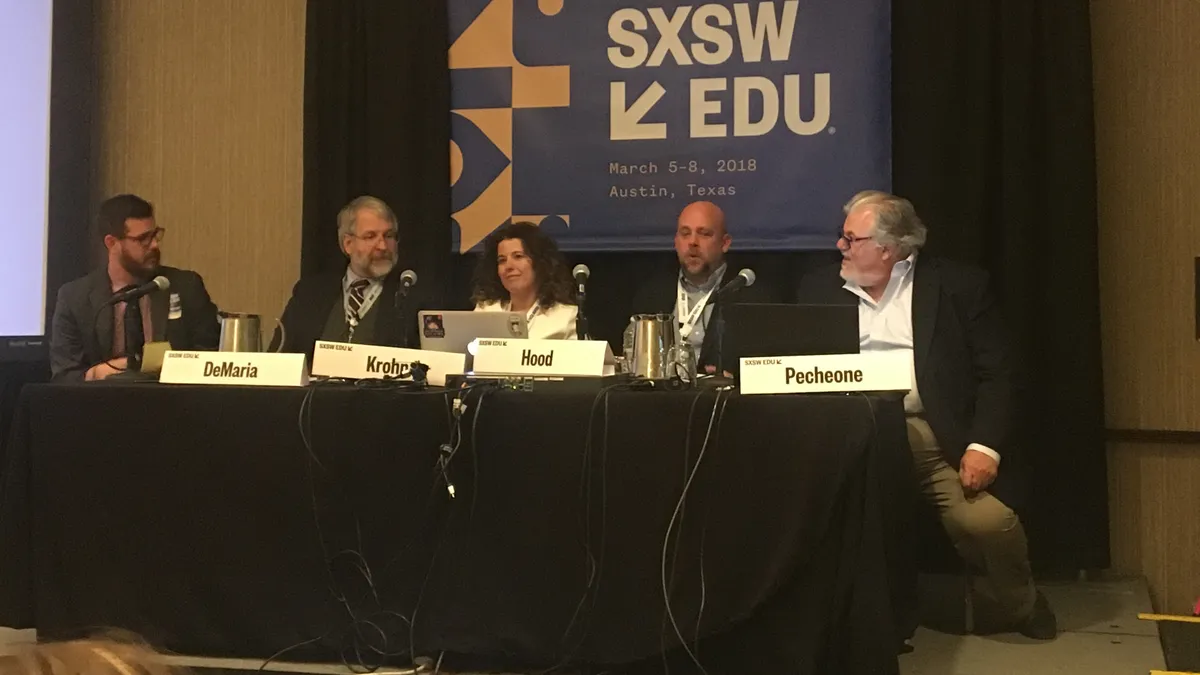

On Wednesday afternoon assessment experts and administrators from Ohio and Texas discussed the approaches they are taking on that front.

The Fortune 500 Most Valued Skills were, in 2010, topped by teamwork, problem-solving, interpersonal skills, oral communication and listening skills, said Ray Pecheone, executive director of the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning & Equity (SCALE). Additionally, deeper learning competencies put forward by the Hewlett Foundation include mastering core academic content, thinking critically and solving complex problems, working collaboratively, communicating effectively, learning how to learn, and developing academic mindsets.

Current standardized testing and curriculum models are not solving this problem. Pecheone cited educator John Dewey's desire for his own children to foster a joy of learning, equipped with the skills and competencies to pursue their own learning, saying that this is at the heart of testing differently.

Barriers to practice in assessing these 21st century skills continue to persist, however, because paced and scripted curriculum that is test-based continue to essentially serve as test prep for high-stakes state assessments. Master schedules are also overloaded, suppressing peer and teacher collaboration. People need time to talk, Pecheone said, adding that the international community knows these things well.

What is performance assessment?

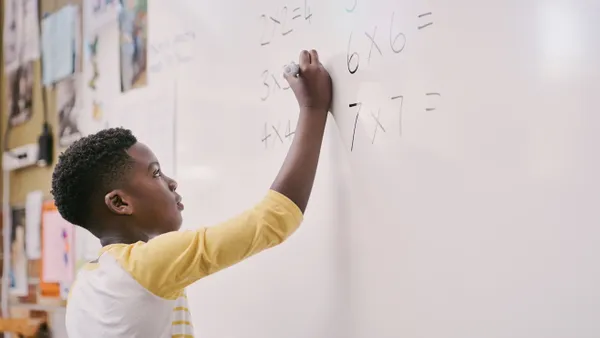

Performance assessment, the panelists explained, is delivered in a range of "grain sizes." The smallest grain sizes are tasks that can be performed in one class period, performed by students on an individual basis, while the largest are essentially projects embedded in curriculum and can take a few weeks to complete. The questions must also be open, providing room for students to find their way to the solution in the ways that work best for them. But the most important aspect, perhaps, is that they make a task authentic for students, providing real-world relevance and context.

Sean Hood, a secondary literacy and language arts administrator for the Lewisville (TX) Independent School District, reiterated this, saying that the tasks must contextualize skills for students as to why they’re important. The study of Shakespearean plays, for example, can strengthen critical thinking around rhetorical messages. It’s about answering the questions of why you need to know this so you can apply it in ways that matter in your life.

“When we sit at the state level, our ultimate goal is two-fold,” said Ohio Superintendent of Public Instruction Paolo DeMaria, adding that leaders have to make the state assessment system make sense.

At the state level, he added, it’s increasingly apparent that, partially due to federal policy, standardized assessments have been put in place as the gauge for how well schools and districts are doing, and as the main tool to measure what students know. But it’s becoming apparent that there are multiple ways for students to demonstrate what they know and can do.

“What we also want to do is create an assessment system that interfaces with good instructional practice,” DeMaria said, adding that he never wants to hear students say that what they think they can do after they learn something, like how to read, is “do well on the test.”

How are states doing it?

The movements toward performance assessment in Ohio, Texas and other states are largely grass-roots.

In Ohio, Christa Krohn, a K-8 instructional math coach, said the Orange City School District, is in the third year of working on performance assessment. They started out with a personalized learning grant from the Ohio Department of Education. First, they had to learn what a performance assessment was, why they needed it, and the “grain sizes” of the assessments. They also had to learn how to author performance assessments.

In the second year, they started looking at the blueprints for standardized tests. They added people to their cohort, which currently includes has six districts in the state. They are field-testing right now, focusing on Algebra I, math in 6th grade, science and American history. To build capacity, they just received money from the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) to train more districts in the state.

Texas' experience has been similar, Hood said, noting that "the want to do it is there" among teachers. Those experimenting want something new, but administrators have to figure out what that means and how to prepare them for this while ensuring reliability in what teachers are seeing.

“Addressing the adult needs in this work is huge,” said Eric Simpson, the director of learning and leadership services for the Texas Association of School Administrators. He noted that a lot of professional learning is needed. The teaching profession is about observing and giving feedback and finding what’s causing the results, and it has to move toward teachers becoming assessors rather than just receiving assessment data.

Asserting that performance assessment, then, should lead students to a deeper level of learning and thinking, having them tackle complex problems in unique and creative ways, the panelists played a video showing examples of performance assessment for math and science. Ohio students at several grade levels were seen collaborating in a peer-learning environment to solve problems around multiplication, volume, and physics.

To provide further elaboration on what these approaches look like structurally, SCALE has developed a convenient resource bank for educators.

The technical realities of being able to flip a switch and use performance-based assessment are still complex, though, because of things like federal requirements. So policy change remains a necessity in the long run. The more states get onboard with these efforts and demonstrate reliable results, the more likely that will become.

“It’s going to be an interesting time to watch how this develops,” DeMaria said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards