Entering high school can be a challenging experience for many students, but Manny A., a rising junior at Edward M. Kennedy Academy (EMK) for Health Careers in Boston, has never had to navigate the transition alone.

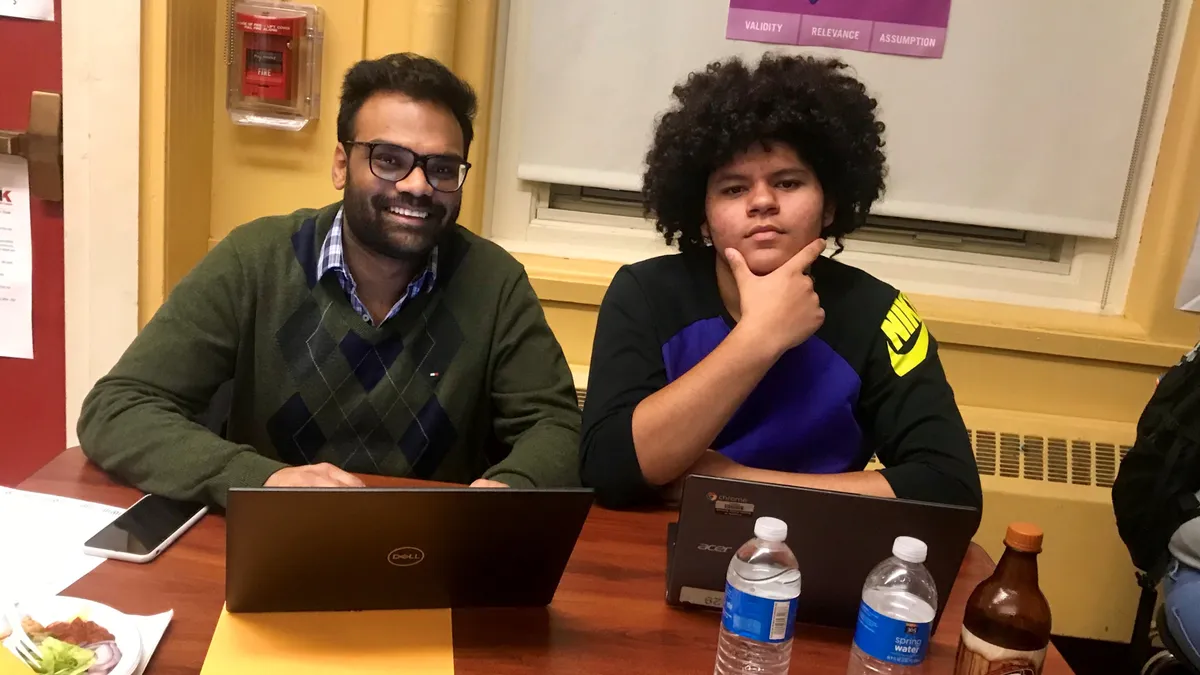

Since he entered the school two years ago, he’s been a part of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Massachusetts Bay’s (BBBSMB) Mentor 2.0 class, which focuses on college and career readiness. And not long after starting 9th grade, he was matched with mentor Bhanu Jain, who provides support — both virtually and in person.

Using the online iMentor model, Jain provides feedback through the Canvas platform when Manny completes classroom lessons, chats with him using a conversation app and meets with him once a month at school where they often play games and discuss Manny’s goals. Jain thinks he and Manny are the “chattiest” pair in the group.

“Those two hours are never enough to cover all the things we want to talk about,” said Jain, a technology specialist at the consulting firm Accenture.

With BBBSMB expanding its Mentor 2.0 program for high school students to a third school this fall — the Community Academy of Science and Health in Dorchester — the organization needs to find 300 college-educated volunteers like Jain to commit to helping low-income and first-generation students headed to college throughout their four years of high school.

The ability to provide a lot of that support virtually is an important recruitment tool.

“This is an opportunity to make a significant impact on a student’s life, within the constraints of the typical busy schedule for urban professionals,” said Cynthia Olson, the managing director for communications at iMentor. “This allows a level of consistency that is critical to building trust in long-term mentoring relationships.”

Extending the commitment

In the 2018-19 school year, 9,009 mentor-mentee pairs used iMentor program, founded 20 years ago by a hedge fund manager and two civil rights attorneys.

BBBSMB isn’t the only site with plans to grow. IMentor expects to expand from 17 to 27 cities through its partnership with BBBSMB by 2022. In addition, iMentor — also available in New York City, Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area and Baltimore in partnership with high schools and other community-based organizations — will expand to two additional regions over the next three years, Olson said.

Mentor 2.0 program coordinators also work in the schools to teach the classes and collaborate with counselors and other educators to align their lessons with the school’s curriculum. They provide “match support” to address any concerns that might arise between mentors and mentees and participate in grade-level meetings when topics such as social-emotional learning are discussed.

The staff at EMK is “really making us feel like an integrated part of the school culture,” said Jaclyn Roache, the coordinator who worked with a 9th grade cohort last school year and will stay with them in 10th grade this fall. She added that the charter school’s headmaster Caren Walker Gregory supports the program by communicating the benefits of mentoring to parents.

While iMentor was originally structured as a one-year mentoring program, the demand to extend it for at least three years came from both mentors and students and allowed the organization to focus more on helping students complete high school and make a successful transition into college.

“When we made the change, many of our partners thought it would be nearly impossible to get volunteers to see a three-year commitment through,” Olson said. “But in fact, about 70% of our mentors see their commitment through.”

Creating ‘personal bonds’

Multiple studies point to the benefits of mentoring for students at risk for dropping out of school. But having a mentor and then losing one because the adult didn’t stick with the program can have a detrimental effect on students who may have already experienced loss and disappointment in their lives.

“Mentors who prematurely end a mentoring relationship may reinforce a youth’s distrust of adults and adult institutions or damage a young person’s self-esteem,” wrote the authors of a brief for the National Center for Mental Health Promotion and Youth Violence Prevention. “Losing mentors, especially experienced mentors, reduces a program’s capacity to serve youth because it requires time and resources to recruit, screen and train new mentors.”

With iMentor, Olson said, the combination of online interaction and in-person sessions creates a more consistent schedule for both mentors and mentees and allows them to form “close, candid personal bonds.”

The fact that mentors know the dates of the face-to-face meetings in advance is another “selling point” for the program, said Kara Hopkins, the associate director of marketing and communications for BBBSMB.

Other youth mentoring programs that involve technology include iCouldBe, Sea Change Mentoring, which focuses on students attending international schools, and CricketTogether, created by education company Cricket Media.

“Accessibility is a key advantage to an online mentoring model,” said Erin Souza-Rezendes, the director of communications for Mentor, The National Mentoring Partnership. “E-mentoring models can combine the best practices of relationship building with new and evolving technology to meet young people where they are.”

As a supplement to its Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring, Mentor is creating a guide on e-mentoring that should be available within the next year, said Souza-Rezendes. But she shared a few tips for school leaders that might be considering mentoring programs with a virtual component.

One is to be “clear and realistic with potential mentors” about mentoring electronically. With Mentor 2.0, for example, mentors and mentees don’t connect on social media. And mentors have to complete at least 90% of the lessons with their mentees to be eligible for the Mentor 2.0 Plus pogram, which allows for additional meetings outside of school, with parent permission, for activities such as college tours, volunteering and job shadowing experiences.

School leaders, Souza-Rezendes said, should also make sure mentors feel supported and that they understand the training and technical support available to them.

‘Spreading the word’

With Mentor 2.0, existing mentors also “play an important role in spreading the word,” said Jain. In 2017, when he was first paired up with Manny, Jain was the only employee at Accenture volunteering with BBBSMB.

Now the company has a team of employees focusing on supporting the organization and hosts field trips for students to give them some exposure to “how the corporate world will look like to them,” Jain said.

The company also holds recruiting events to attract more mentors. Last year, 12 employees participated in Mentor 2.0 and seven served as “bigs” in the traditional community-based mentoring program for children 7 to 12 years old.

Now that Jain and Manny have been connected for two years, they are approved for the “plus” level. Jain has been doing some research on summer job opportunities connected to Manny’s plans to combine his interests in health care and technology.

“He is the best,” Jain said. “He has this energy that is always fascinating to me.”