Though school districts had to increase recruitment and retention efforts to address bus driver shortages long before COVID, pandemic-related challenges have led to unprecedented transportation headaches for many nationwide.

In a joint survey from the National Association for Pupil Transportation, the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services, and the National School Transportation Association, about two-thirds of all respondents (65%) said the bus driver shortage is their No. 1 problem or concern.

“We have not witnessed a shortage like this in over 100 years of our operations,” said Anna Lam, a communications specialist at National Express, LLC, an Illinois-based transportation firm. “The shortage has varied from region to region.”

The regional differences were also highlighted by survey respondents: 79% in the Northeast said they have altered service, compared with 77% in the Midwest, 66% in the South and 80% in the West.

Financial incentives can help bring in new workers, but as the “Great Resignation” sweeps across all industries, increased compensation isn’t necessarily a cure-all.

“We have seen varying degrees of success with sign-on bonuses at our locations,” added Lam. “We have also adjusted our starting wages to be above averages in most local markets and have seen some increased interest.”

In addition to pay boosts and joint recruiting efforts with contracted transportation providers, school systems are adopting a variety of additional strategies to lessen the pressure of driver shortages.

Changing routes

In Montana, Helena Public Schools trimmed 15 routes off its traditional 68. The school contracts with First Student, a charter bus rental company that specializes in school transportation, to manage the hiring, training and management of drivers. In the past, recruitment efforts outside the immediate community, even out of state, have yielded success. But given the massive shortages in all transportation industries, that is not an option.

“It is really tough right now. We have other school districts around the state just cancel routes if they don’t have drivers. Instead, we’ve been rearranging routes to make changes,” said Drew VanFossen, transportation operations manager for the Helena Public Schools. “We are strategizing and slowly revealing that we’re going to reimburse parents for routes that do not run.”

Instead of an all-out shift to no transportation, the Helena schools are providing a rotating schedule. That means students could catch the bus for three weeks and on the fourth week use alternative methods for getting to school. The school would help families offset the cost of transporting kids the week their route doesn’t run.

“Looking at ways to improve efficiencies by identifying opportunities to decrease routes can be part of a workable strategy while working to attract new drivers,” VanFossen said. “It’s also critical to be consistent with the message to parents in terms of the routing you’re doing.”

Adjusting bell schedules

Most buses ran on two-hour delays at the Rochester City School District in New York the first two weeks of the school year. The district is short 125 bus drivers, according to Chief of Operations Michael Schmidt.

Instead of a two-tier bell schedule, a third tier has been added to the traditional 7:30 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. start times. Reviewing the route combinations and maximizing each driver’s routes have eliminated the delays. Buses have been suspended for most students living within 1.5 miles of school, with exceptions made on a case-by-case basis.

“It’s not good. We have not solved this thing, but we have stabilized our situation, and it is much improved since the first couple of days of school,” Schmidt said. “Any time you deliver news that is not favorable to families, the conversations can become difficult. Be completely transparent. We explained all variables to the situation we were in, and the parents have been great.”

In September, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul announced the option to activate the National Guard to take the wheel and help transport kids to and from school. Utica City School District is among those that have requested the solution.

“We’ve certainly had conversations about using the National Guard. I think if what we experienced the first few days had continued, it would have been more likely as an option,” Schmidt said. “In part, there is the question of how long that is sustainable. Eventually, those services would come back in-house. For that reason, we’re trying to do with our own relationships and resources first to solve as many problems as we can.”

Partnering with public transit

Granite City Community Unit School District #9 in Illinois is 28 drivers short. The district transitioned from a two-tier system — running three groups of buses on two school routes — to a three-tier system where two groups of buses are running three school routes. But even that wasn’t enough.

The district contracts with Illinois Central School Bus rather than owning a fleet. This year, the district is partnering with ICSB to amplify recruiting efforts.

“Unfortunately, we had to cancel all buses for 5th through 12th grade,” said Chris Mitchell, manager of district communications.

“We have partnered with Madison County Transit to provide free transportation for students whose bus routes are still inactive,” he said. “We are currently in the process of bringing those back and have brought back eight of 15 routes as of Oct. 20, 2021.”

Understanding staff needs and concerns

When the pandemic first hit Clayton County Public Schools in Georgia, bus drivers delivered meals to the community across 227 routes, said Denise Hall, director of transportation for Clayton County Public Schools.

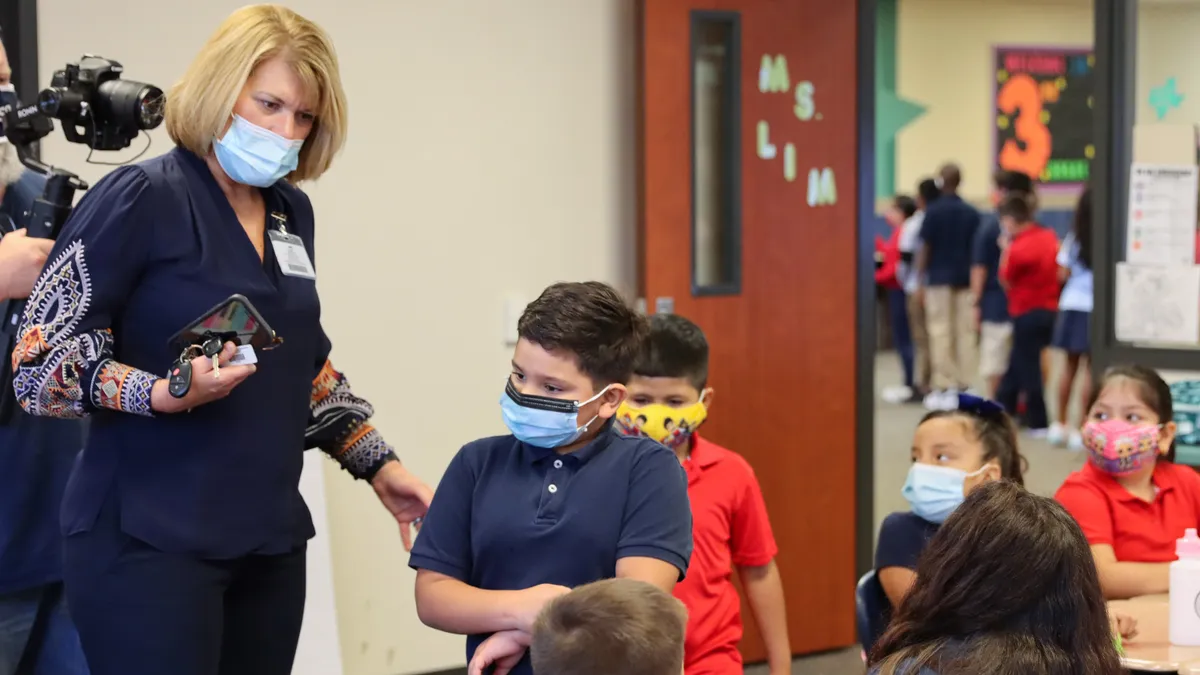

“We had enough staff to perform these duties. When the district returned to in-person learning, we started receiving resignations from our staff. The resignations increased as staff struggled with driving large populations of students who did not wear masks,” Hall said.

In addition to raising salaries and offering incentives, masks were made a requirement on school buses.

“Drivers and monitors want to be valued and protected while transporting students in the midst of this pandemic,” said Hall. “As leaders, we must understand the important role they play within the organization. It is our responsibility to give them the necessary tools to be successful and work in a positive environment.”

Utilizing rideshares

Ridesharing is a relatively new solution to solving personal transportation needs, and the model offers an alternative approach for alleviating student transportation challenges amid bus driver shortages.

One advantage, according to Joanna McFarland, CEO & co-founder of student-centered rideshare service HopSkipDrive, is that technology is built into the entire process. The team monitors the ride, and parents and caregivers can use mapping to see exactly where the student is.

“School districts have not had easy access to that, and there is always the question, ‘Where is the bus? Is my bus late?’ With this, everybody knows where kids are on the entire way to and from school,” McFarland said. “We had 100 new contracts with schools come in during the pandemic.”

The "care drivers" at HopSkipDrive are independent contractors who are rigorously vetted and fingerprinted and must have five years of caregiving experience. They are also people who live in the community.

Meanwhile in Chicago, mass driver resignations left families in Chicago Public Schools with no way to get their kids to school. Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s office is in talks with rideshare companies, according to the Chicago Sun-Times. While conversations with Uber and Lyft are ongoing, and parents are receiving stipends to cover travel until regular services resume.

Are self-driving buses an option?

While the Hanna-Barbera animated comedy “The Jetsons” relied on robots to alleviate life’s pain points, autonomous vehicles won’t likely be a solution to the bus driver shortage in the immediate future.

French transportation company Transdev was part of a short-lived pilot program in 2018 to transport students to Babcock Neighborhood School in Florida. The federal government quickly stepped in and suspended the project over safety concerns outlined by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

There is still a long road ahead, but every crisis brings an opportunity, according to Rochester’s Schmidt. The bright side to this situation is a significant mindset shift to recognizing the value of the work people perform behind the scenes.

“I’ve worked in operations for a number of years with food providers, bus, custodians, support personnel and security, and I am seeing a lot more thank-yous and recognition of the efforts people are putting in,” he said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards