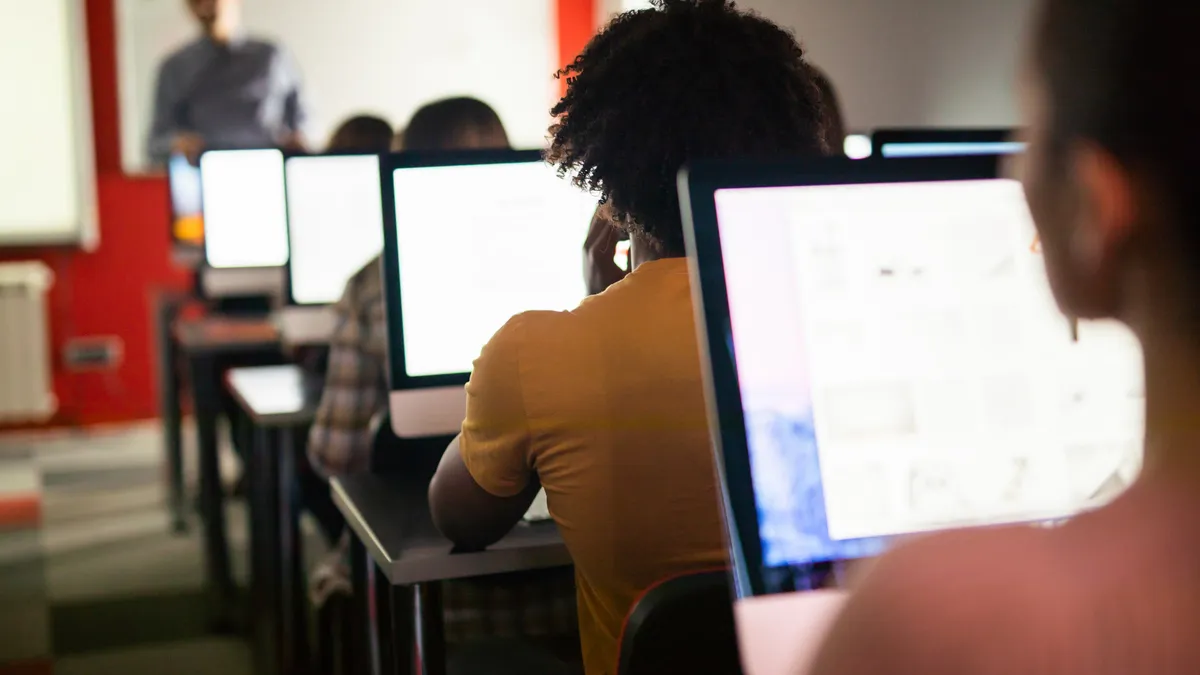

Giving students more voice and choice in their learning has grown in focus alongside a push to transition from an industrial-era assembly line model of public education to one more aligned with modern needs. Today’s students are more likely to need skills in areas like agency, time management and creativity, necessitating less directed instruction and hard boundaries.

This, however, is easier said than done.

In her new book “Teach More, Hover Less,” Miriam Plotinsky, an instructional specialist at Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland, identifies strategies gleaned from over two decades teaching and leading in her district. We recently caught up with her to learn more about how educators can engage students with more voice and choice in their learning across curricula — yes, even in math.

K-12 DIVE: How would you define hover-free teaching?

MIRIAM PLOTINSKY: Hover-free teaching is something I started developing through the years because — and this is something that I see consistently, and even more so now — teachers work too hard. And the thing about working hard is that if you're working really hard, you want to get a return for that. You want students to benefit, and you want to have a classroom that shows the fruits of that labor.

But I found it to be kind of the opposite — that the more we were controlling our instruction, the less students really seemed to be interested or engaged in what was happening.

There’s this metaphorical thing that happens where we're holding onto students with both hands, and then we gradually take one hand away and then the other, and the question was, “How much do we really trust students to learn on their own without us forcing the process at all times?”

That's really what hover-free teaching is. It means that we have the belief not just that students can learn, but that students will take responsibility for their learning if we create the conditions that make it possible for them to do so. And I know that sounds very idealistic, and that's why I wrote “Teach More, Hover Less” as a guide with specific strategies. The book is full of very specific tools you can implement to try or adapt based on your own practice and what you teach.

The overall trend in education over the last, at least, decade has really been in that direction, where it's more about giving students voice and agency in their learning as opposed to just talking at them. What are some of the best ways you've found to put that into practice as an educator?

PLOTINSKY: One of the stages is about building deeper relationships. I know we talk a lot in education about building rapport with students, but that's not really what my book is talking about. It's about actually building this sort of relationship where students can take academic risks in the classroom and not feel as though they're being put on the spot or devalued.

For example, I might offer some strategies for when a child raises a hand and offers an opinion for the class or offers a contribution. As teachers, either consciously or unconsciously, there's an agenda we have. There’s an answer we're expecting. And if we respond the wrong way, even if it's a nice response, we could shut the student down accidentally and not make it that kind of deeper academic-based relationship. So that's one area I move along in the book in ways to really validate what students think.

When we think about how we plan for student engagement, we tend to plan in bubbles a lot. We guess what students might want. We hypothesize when really we could be asking them more. When I teach my classes, I ask what's working, what's not, what do you want to see more of. Based on what students tell me, I make changes. And I bring it back to them and say, “OK, here's what we're gonna do today. Let's see if it works.”

That way, they're seeing the real-time implementation of what they said they wanted to do. That's one way to build that trust that they're actually managing more, and I'm not trying to figure out what they want, because they're telling me.

Another thing I talk about a lot is choice. When I wake up in the morning, I might have five things on my to-do list I have to accomplish by the end of the day. For example, I write every day, because I'm a writer. And I know that I do that best first thing in the morning.

But students are in this position where they can't pick what they do. So they come to school, and they're supposed to perform on demand. And while a lot of people have, in the past, praised that as a skill set, they should be able to focus and get the work done.

What I propose in my book is that at certain days or certain times we should be giving them some choices that still fall in with our instructional priorities and that they can also self-select. So we meet in the middle.

There are some subject areas where it might be easier to take this approach more immediately. But even in subject areas like math, for example, that feel more direction-based, are there ways to give students more agency that are often overlooked because the focus is more on the specific problem or formula and not applications of where you actually see it used in the world?

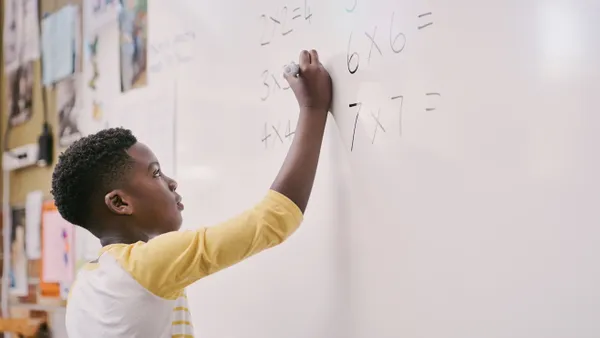

PLOTINSKY: There's actually, in the book, a tale of two classrooms, where it moves through a math hallway and teachers are teaching the same thing, but one of them's doing it in a more teacher-directed way and one of them's doing it in a more student-centered way, so there's a tangible difference readers can see between those two.

I learned a lot about something called illustrative mathematics. That's where instead of a teacher getting up in front of the class — as is very traditional in certain math courses — and showing a problem and then having students do a problem, there's a picture, for example, and students look at it and develop questions about it. Maybe they're looking at a graph, or maybe they're looking at something else or a problem.

First, they develop all these inductive questions. And what that does is open up, first of all, more language production. There's more discourse, they're having conversations. And then if they share their conversation with a larger group, it's something they develop together. And the teacher uses strategies.

For example, they might pick one I write about called “my favorite mistake,” where you actually learn to celebrate wrong answers because they lead us to learning. So even in the more concrete content areas where you have yeses and noes, when it comes to answers in a much more tangible way, you can still use some of these strategies to help students feel as though no matter what they know or don't know, they all know something that can help them learn, and that it's OK to move together toward something with that more inductive approach.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards