Dallas Independent School District leaders say a bold approach to reforming discipline practices by eliminating most traditional in-school and out-of-school suspensions is showing promising results in its first year of implementation.

As an alternative to suspensions, Reset Centers opened last August at 60 of the district's comprehensive middle and high schools to give students time to de-escalate and discuss their behaviors with trained staff and other students.

During the 2020-21 school year, the 145,000-student district recorded 4,800 out-of-school suspensions and 1,100 in-school suspensions. This school year, the first year of discipline reform, there have been 1,168 referrals to Reset Centers, with about 100 students having a second referral, said Superintendent Michael Hinojosa. Those numbers were as of May 2, about a month before the school year was set to end.

"We didn't just tinker around with the past. We created something completely new," Hinojosa said.

But it wasn't as simple as rethinking suspensions. The district also set goals for strengthening tiered student behavior supports, boosting teacher training for classroom management, and improving data collection for better decision-making about effective, fair and individualized responses to student conduct violations.

For example, where the use of profanity may have triggered a punishment of in-school suspension, now educators have a list of options to consider for first, second or third offenses. Those options include creating a behavior contract, before- or after-school detention, peer meditation and others, according to a district document developed last year.

Higher-level offenses, such as harassment against a fellow student, assault or fighting, could result in assignment to a school's Reset Center for up to three consecutive days.

The district spent $4 million from its Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief allocation for the discipline reforms. Hinojosa said the school system has realized $2 million in cost-savings because fewer students placed in out-of-school suspensions resulted in higher daily average attendance. Texas school districts are funded based on in-person daily average attendance.

'Putting a Band-Aid on cancer'

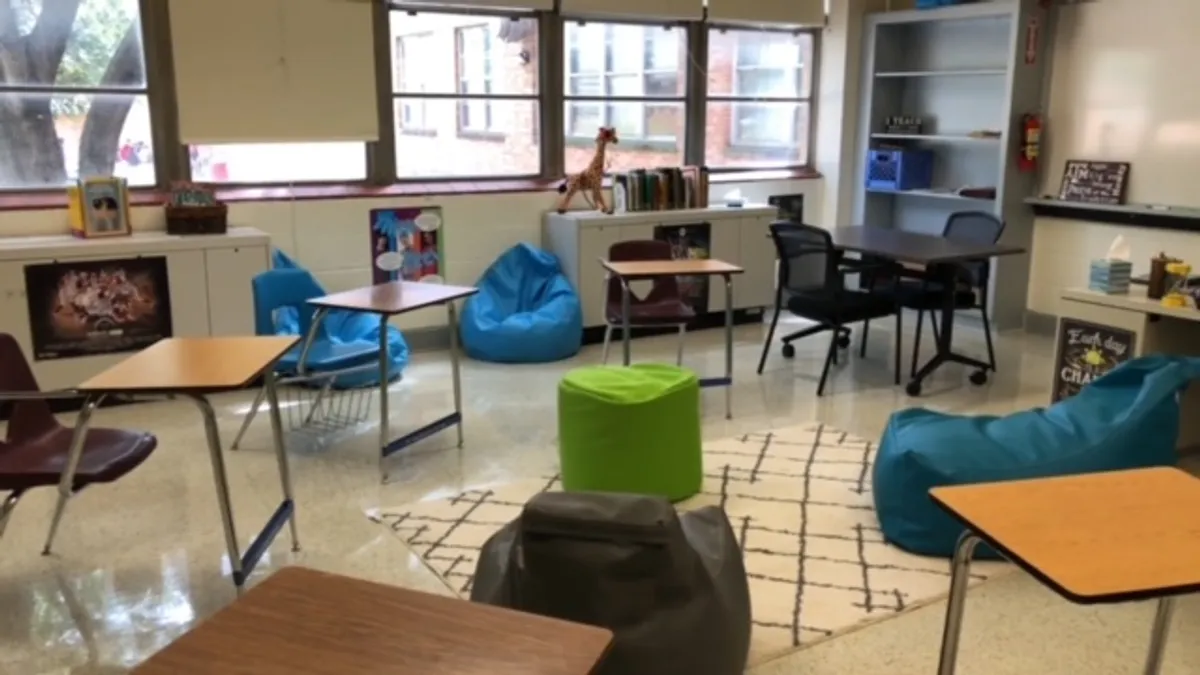

The Reset Centers' dedicated classroom spaces feature seating for restorative circles, calming colors, flexible seating to allow for movement, and stress squeeze balls and fidget tools.

Students who commit an infraction can be in the Reset Centers for less than a few hours or for several days.

In addition to discussing the underlying causes of their behaviors, students are expected to keep up with classwork. The district's Department of Teaching and Learning has been helpful in organizing asynchronous lessons to students at Reset Centers, Hinojosa said.

Pierre Fleurinor, a Reset Center coordinator at the 1,100-student L.V. Stockard Middle School, said he's seen positive differences in student behavior under the new approach as he and other teachers take time to build relationships with students.

Fleurinor, known at the school as Coach Flo, was an in-school suspension teacher before this school year. "I feel like Reset has made it easier for kids to realize that we're not just here for a paycheck. We're actually here for them," he said.

As a Reset Center coordinator, Fleurinor said he's received professional development in mindfulness, social-emotional learning, behavior management and positive relationships.

Fleurinor not only works with students assigned to the Reset Center but also with the school's other teachers on classroom and individual student behavior solutions. The emphasis on positive behaviors has helped adults at the school reduce student conflicts before they escalate, he said.

"Before, I felt like ISS [in-school suspensions] was like putting a Band-Aid on cancer. We were never addressing the real issue," Fleurinor said.

Hinojosa said the new approach emerged from a desire to eliminate disproportionate suspension rates in the district. Before the pandemic, African American males made up 13% of the student population but 51% of out-of-school suspensions, he said.

"And so during the pandemic, I just asked a rhetorical question: Why would I ever suspend a student again?" Hinojosa said.

In researching its discipline practices, the district discovered 80% of suspensions were discretionary, meaning the punishment for student conduct violations was based on subjective determinations. The other 20% of suspensions were mandatory based on the violation. The district still carries out mandatory suspensions for specific high-level offenses, HInojosa said.

After district staff suggested the discipline reforms, it took three months of planning, listening sessions, hiring and training before the centers opened.

Making modifications

Hinojosa said he's visited most of the Reset Centers. "Everything I've seen is great. Everything I hear is not," he said.

He explained that during his visits, he sees Reset Centers staffed by professionals with training in behavioral supports and students voluntarily coming by to talk with Reset Center coordinators.

But, Hinojosa added, a handful of campuses have been reluctant to eliminate suspensions. Extra resources have been invested at those schools to help make the change, he said.

"There are a few people that are frustrated with such a drastic change overnight," Hinojosa said.

"I believe that perfect is the enemy of great, and I think we're onto something great here. And we need to keep fixing what's not working, and we have to be humble and gracious enough to listen to people when they talk to us about the issues that are still out there."

.@DallasSchools used #ARP funds to support a new approach to school discipline by eliminating discretionary out-of-school suspensions and setting up Reset Centers at middle and high schools. Staff help kids reset behavior, while they stay engaged in schoolwork. #ARPStars @usedgov pic.twitter.com/kysfjT1bGb

— Chiefs for Change (@chiefsforchange) March 11, 2022

Fleurinor, meanwhile, said at first some students did not want to discuss their emotions or own their behavior, but as the school year progressed, he has seen more buy-in.

"I think persistence has shown that what we're doing is working," Fleurinor said.

In preparing for the change, district leaders held meetings and requested feedback from teachers, students, school administrators and parents about discipline approaches. Students said some of the "dumb" reasons for in-school suspensions included dress code violations, sleeping during class and being late to class, according to the district's document.

During the district's listening sessions, students suggested different approaches to in-school and out-of-school suspensions such as making sure they get the right help and encouraging teachers to get involved with students by attending sporting events and other activities.

As the district looks toward next year, it is planning to keep its discipline reforms in place, including the Reset Centers. District leaders will review end-of-year data — including discipline rates, disparities in discipline, academic progress and more — and make modifications where needed, said Hinojosa, who is retiring at the end of this school year.

His reforms could have legs beyond Dallas, though. Hinojosa said the district is getting inquiries from other school systems interested in similar approaches.

"We're very fortunate it's gone very well at most schools, but you got to listen to your people on the ground once you start implementing," he said.

Fleurinor predicts the changes to discipline practices this school year will have positive long-term effects.

"School is tough enough on its own for some kids to just wake up and come to and focus and work. When they know someone cares about them, that deposit right there, it gives us an opportunity to make a withdrawal in the classroom," he said. "And every time we do that, I feel good about what we're doing."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards