SAN DIEGO — Speaking to district leaders at last week’s National Conference on Education, Stanford University education scholar Linda Darling-Hammond laid out a “personalization agenda” to address the achievement gap. And it didn’t include 1-to-1 technology.

Listing models such as student advisory programs, smaller schools, block scheduling and looping to the next grade with students, she emphasized the role of relationships in supporting learning and reversing some of the effects of trauma linked to poverty.

Learning is “catalyzed and shaped by human relationships,” she said, showing a video of a teacher giving a special handshake or fist bump to each child as he or she enters the classroom and another of her adult daughter having a “conversation” with her infant.

Community schools with integrated services for students and having schools with longer grade bands were also on her list. “The fewer times you change schools, the higher the achievement,” she said.

Darling-Hammond, also president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute, began her comments during Friday’s general session by saying she was surprised when the personalized learning movement began to mean “what happens when you sit kids in front of a computer with an [artificial intelligence] program that leads them through a program of instructional sequence.”

But she followed up by saying the “right blend of teachers, peers and tech” benefits students if they are using technology to create, explore, collaborate, play games and conduct research on topics of interest.

In keeping with Thursday’s discussion on how school rules and policies can sometimes trigger negative reactions in students, she described a high school her daughter once attended that locked the doors after the bell rang in the morning and told students to go home if they were late. Those who rode the bus longer distances tended to be black and Hispanic and were often the ones sent home for being tardy.

She also talked about “multi-tiered systems of support” — a term for moving from universal instruction and support for all students to more targeted, one-on-one services depending on students’ needs. A series of research briefs on California’s special education system released Tuesday suggested the state’s school leaders and teachers need more training in how to implement such a model.

The special education process, she added, is full of “bureaucracies,” such as Individualized Education Programs that can delay a student receiving services by months or longer.

“We’ve got figure out how to reduce that impediment so we can figure out how to get kids what they need when they need it,” she said. “Educators care, but we’re stuck in structures where it’s hard for us to care effectively.”

Leaders discuss move toward personalization

In a later session, the role of technology in personalizing learning was more prominent as Tom Vander Ark, CEO of Getting Smart, “a learning design firm,” led district leaders through a discussion of what personalization — the overall theme of the AASA conference — looks like in their schools.

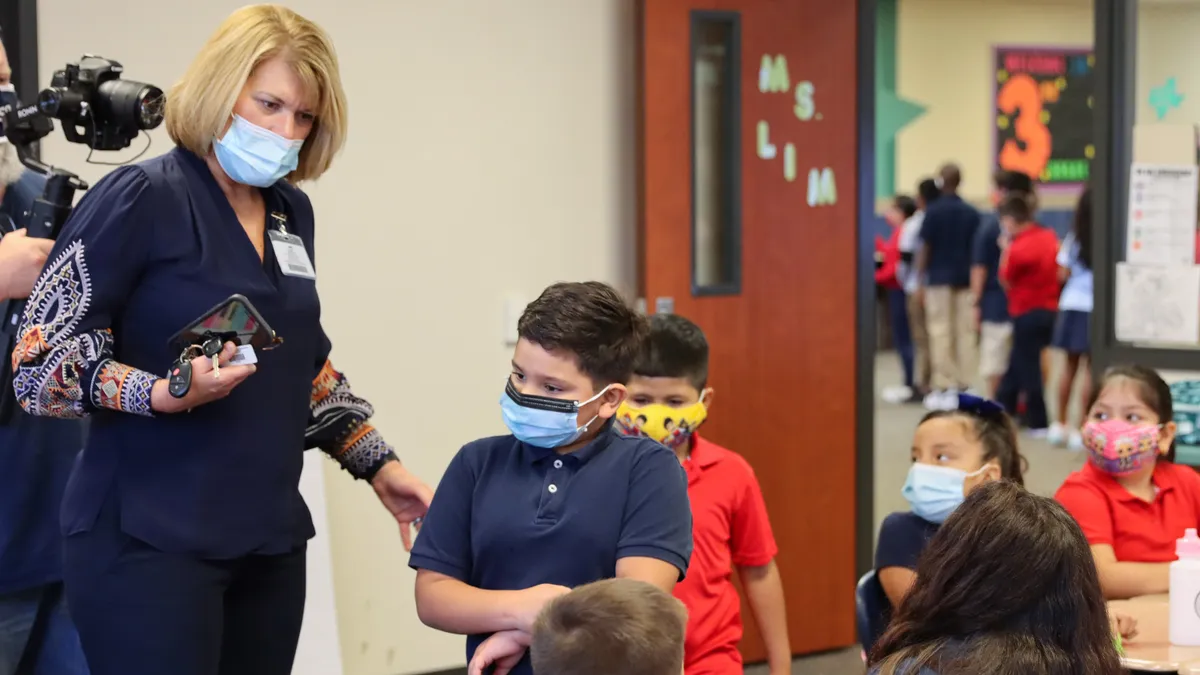

In the Dallas Independent School District in Texas, technology and new classroom designs are a large part of allowing district schools to stand out in an increasingly competitive environment.

“Charter schools are hemorrhaging our enrollment, so we decided we have to compete with them,” Superintendent Michael Hinojosa told attendees. Personalized learning models are incorporated into the district’s Transformation and Innovation Schools, which are similar to magnet schools and admit students through a lottery. The district also offers a technology integration “toolkit” that describes the various tools DISD teachers and students are using and the purposes they serve.

In the Meriden Public Schools in Connecticut, Superintendent Mark D. Benigni began leading a bring-your-own-device initiative about 10 years ago and hired technology integration specialists to work with teachers on embedding digital content into their teaching.

“We’re not saying tech is replacing you,” he said he told the teachers, explaining that with some instruction provided online, teachers would have more time for working with individual students or small groups.

Changes include a no-zero policy. “If the work matters and we’re assigning it,” Benigni said, “we’re going to find creative ways for students to achieve it.” And partnerships include “Web Wednesday” events in which high school students help senior citizens learn tech skills.

Mark Bedell, superintendent of the Kansas City Public Schools in Missouri, explained the pitfalls of assigning laptops to students without first addressing a range of IT infrastructure issues. The network was 15-years-old, firewalls needed replacing, there was no ability to monitor what students were doing online and many devices couldn’t hold a charge.

“We just rolled it out, and it became a glorified textbook,” he said.

Students were also allowed to take devices home, but leaders quickly discovered the majority of students didn’t have internet access at home. He once found a student sitting outside a school at dawn so he could get WiFi to complete his homework before school. Now in a partnership with Sprint, the district provides high school students hotspots to use at home as long as they are enrolled.

“We had created more inequities while we were in the process of trying to give our kids a much richer experience,” Bedell said.

The panel also included Lydia Dobyns, president and CEO of the New Tech Network, which now includes 200 schools using a project-based learning format, of which 1-to-1 technology is a large part.

The project-based approach, she said, is often misunderstood and is not the same as doing a project at the end of a unit. Vander Ark, who wrote a book with Dobyns on school networks, said he likes that New Tech schools use team teaching and provide instruction in integrated blocks.

But the model is also a significant “lift” for teachers, Dobyns said. “The easy part is starting, and the hard part is persisting over time,” she said, adding she hopes more school board members will support these types of models but also understand they take time to implement. “Every district we meet with wants it fast and cheap.”

Another network is the 400 schools using the Summit Learning platform, which also involves project-based learning and elective opportunities for students to study what interests them. But Katrina Stevens, the director of learning science for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which has provided funding for Summit, said students need “scaffolding” to become more self-directed. Students, she said, “are so used to doing what we tell them to do.”

Apprenticeships that give students ‘an edge’

M. Ann Levett, superintendent of the Savannah-Chatham County Public School System in Georgia, often tells students when they finish high school, she wants to see them enlisted, enrolled or employed.

And now with a wide array of youth apprenticeship opportunities in industries such as aerospace, health care, and travel and tourism, students will be better-prepared to “sustain themselves and their families,” Levett said during a Friday session on implementing youth apprenticeship programs — another form of personalizing education.

Even if students pursue college, many will still need a job while they are earning a degree. And if they go straight into the workforce, an apprenticeship program can give them “an edge,” she said.

“We want them to be prepared for the future that we don’t know very much about,” she said. “I want them to be prepared to live and work wherever they want in this world.”

The Cherry Creek School District in Colorado now has 50 apprenticeship programs along with a $64 million Innovation Campus where students can pursue workplace learning opportunities within nine different pathways. Voters approved a bond issue in 2015 to fund construction of the facility.

“We really looked at what jobs are available today that students can go into,” Superintendent Scott Siegfried told attendees, adding the district changed its thinking from “college for all” to “college and career preparedness for all students.”

“Nobody tells me their goal is that their kid goes to college,” Siegfried said. “Their goal is that their kid has a great life. For some kids, the pathway is an apprenticeship.”