In Denver Public Schools, supporting the “whole child” includes supporting children’s parents.

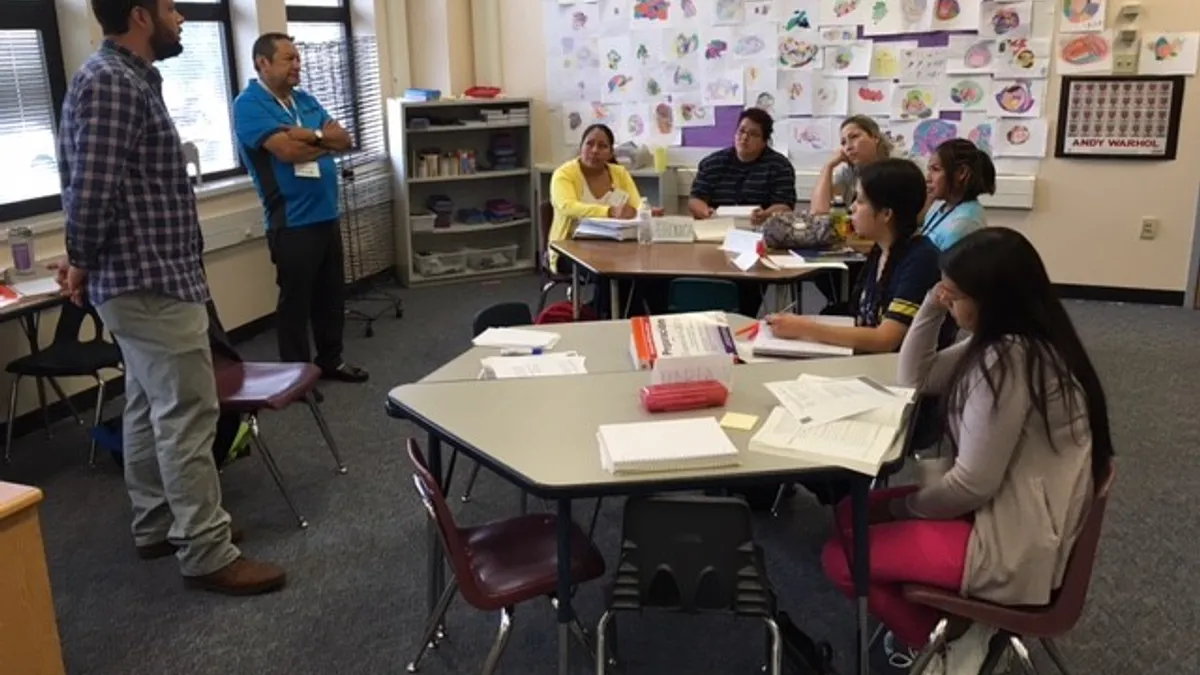

The district’s Center for Family Opportunity, funded through a collaboration with the Mile High United Way and run with a variety of local partners, offers parents financial coaching, career development services, English classes, paraprofessional training, citizenship classes, GED classes, and early learning and language literacy supports for parents with children younger than 3.

Lindsay McNicholas, director of adult and youth services at Denver Public Schools’ Office of Family and Community Engagement, oversees the Center for Family Opportunity, which is based at College View Elementary School on the city’s southwest side. This area of Denver is primarily low-income and a key source of participants for the center’s programming — 65% of them, in fact — but anyone over the age of 18 in the entire Denver metro area is eligible for the free classes, and people come as far as the far northeast side.

McNicholas says the commitment to improving family stability has a direct impact on students in the public schools.

“That instability trickles down to kids,” McNicholas said. If parents are stressed out about housing, money, immigration status or work, it impairs their children’s ability to succeed in the classroom.

That’s the logic behind the Center for Family Opportunity. By focusing on the family unit as a whole, Denver Public Schools leaders and their partners hope to address intergenerational poverty. Connecting parents with stable employment, stable housing and continuing education opportunities is expected to give kids room to thrive in and out of school.

“That’s the key,” McNicholas said. “We need parents to be stable so they can help support their kiddos through their education and alongside the school administration.”

The “community schools” model has become increasingly popular as policymakers and education officials recognize the limits of a school’s sphere of influence. Schools can’t overcome all the barriers presented by family and neighborhood poverty and violence. They can, however, be a home base for broad-based initiatives that cluster supports for entire families and aim to break cycles of poverty.

This work is more important than ever. At a time when family income is becoming even more predictive of student achievement, educational attainment is arguably most influential for social mobility. And it tends to fall to schools to help students overcome their odds.

Some communities have tried to cluster services to make it easier for families to improve their lots, but in Denver, McNicholas said basing the effort at a school has been a high priority. As the district looks to expand the Center for Family Opportunity, it is only looking for additional locations in schools. There students can see their parents setting goals and accomplishing them, parents can be involved more directly with their children’s academic work, and families can build community among each other.

Already attendance is up at College View Elementary School where, if parents are going to class, kids are, too. And the school, as a whole, has also gone from the lowest of five levels in the district’s rating system to the second, which means it is now meeting expectations.

Programs are held every day, both during school and in the evening. Childcare is always offered so parents with young children can still attend. And staff members encourage bundling services. If parents come into the center seeking English classes, they are encouraged to consider career development or parenting classes, too.

And the career development focus has benefited both parents as well as the district. New pipelines have been built up between the center and Human Resources, especially in departments that hire large numbers of people every year like transportation, facilities management, and food and nutrition services.

Nestora Duran is one beneficiary of the hiring pipeline. After taking classes at the Center for Family Opportunity, she got hired to work in the kitchen at the Bruce Randolph School in Denver Public Schools.

“Thanks to the CFO we are more financially stable now,” Duran said. “I am less stressed and I’m happier. We are at a higher economic level.”

The district has also been able to hire paraprofessionals from the parent pool, benefiting from their knowledge of multiple languages.

So far about 950 people have been served in three years of operations and 460 of them were served this year. As the center expands its outreach efforts and word-of-mouth increases demand, McNicholas and her team are looking ahead to a possible second location. Like most initiatives, expansion will depend on finding the funding to support it.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards