The U.S. Department of Education this week released state plans to spend historical levels of federal aid funding provided by the American Rescue Plan — the last third of which the department withheld and are now on the horizon.

The approved 28 of 51 plans submitted from states and the District of Columbia include permutations of the expected: strategies for academic recovery like high-dosage tutoring and enrichment programs, social-emotional support for students, training for school staff and other ways to ease students back into the classroom.

Some priorities are short-term, like continuing COVID-19 mitigation strategies, providing teacher bonuses and expanding access to vaccines.

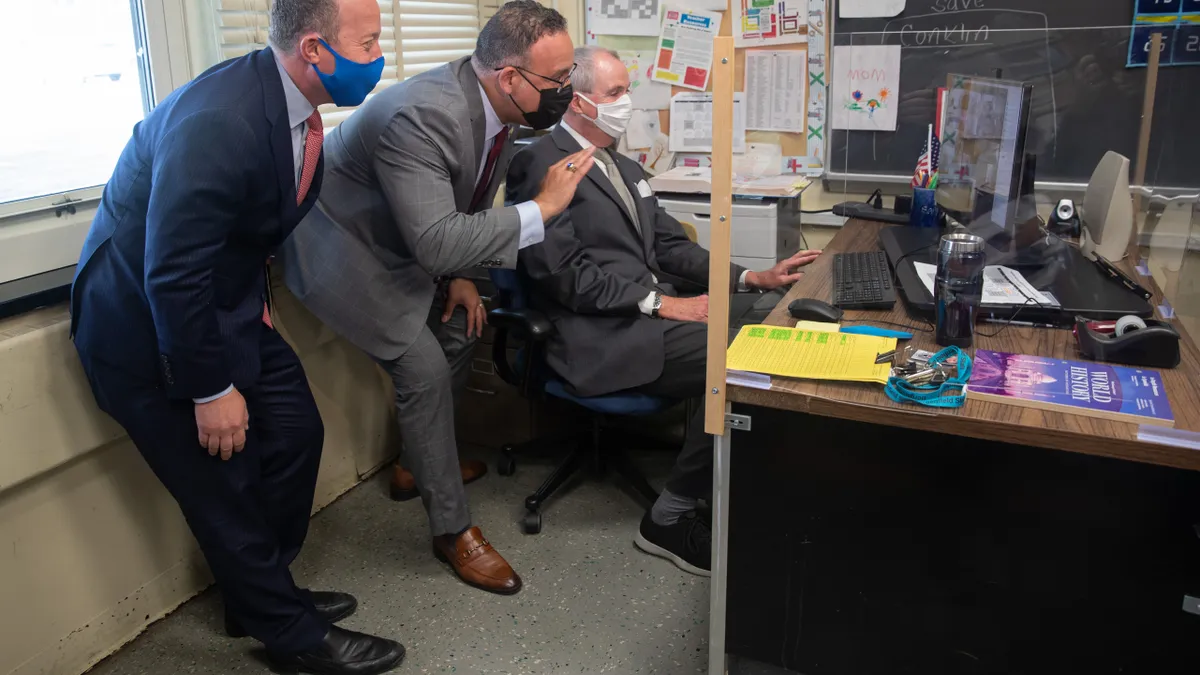

"What I did want to see — I saw — were social-emotional mental health supports, a focus on equity, and an engagement of different stakeholders to make sure we are listening to those impacted most by the pandemic," said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona.

State plan delays signal difficulties in short-term planning

However, due to legislature and state board review delays, nearly half — or 23 states — haven't yet filed their plans, the last of which will be submitted in late August, according to an Education Department spokesperson. And most states that submitted their plans didn't quantify their spending proposals for Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund III, or the third pot of ESSER money provided by the federal government through ARP.

"We want to make sure that the money is getting to the classrooms as soon as possible and we are working with states where it's been communicated that that's a little bit of a delay," Cardona said, adding $81 billion of the ARP funds have already been released. "If there is any district that doesn't have access to funding, we need to be in conversation with them."

Sasha Pudelski, assistant director of policy analysis and advocacy for AASA, The School Superintendents Association, said the delays in state plans are a telltale of the difficulties both state and local leaders are facing while planning for and managing oversight of a sizable expenditure in a short period of time.

"Districts aren't waiting to see what are in state plans to come up with their own plans," Pudelski added. "They are forging ahead with what they are hopeful the allocations will be."

As fiscal cliff approaches, eyes turn toward sustainability

According to the Edunomics Lab, a non-partisan education finance research center tracking ARP plans and spending, states that submitted their plans most commonly mentioned distributing their portion of the ARP ESSER funds to districts and vendors or organizations like museums, zoos, historical sites, state parks and the state fair

for student admission.

Meanwhile, districts have discussed prioritizing students facing disadvantages, such as students experiencing homelessness and poverty, students of color, students with disabilities, and multilingual students, all of whom have been disproportionately impacted by school closures.

"I'm tired of seeing data disaggregated by race and place be a better determinant of their success than their aptitude," Cardona said. "I expect there to be transformational change around issues of inequities that have plagued our education system since we've been collecting data, and I'm confident with great resources and great leadership, we're going to get it done."

Though as a funding cliff approaches and districts plan to spend their allocations, both superintendents and education finance experts are calling viability into question, as ARP funds may not be enough to sustain the programs and staff necessary to support those students' academic and social-emotional recovery. In fact, state plans specifically pointed to a dearth of special educators and paraprofessionals, school psychologists and counselors, and bilingual and English Second Language teachers. "That's been a documented pipeline issue," Pudelski said.

And because ARP funds are only expected to last for a handful of years as districts claw their way forward from COVID-19 setbacks, some superintendents are hesitating to invest in such long-term programs and staff. Others are making the leap, crossing their fingers for states to step in when the aid runs dry.

According to Jess Gartner, founder and CEO of Allovue, a firm that specializes in financial solutions and services for school districts, the lump sum of all three ESSER funds amounts to just under $4,000 per pupil to be spent over six fiscal years. That's approximately $650 per pupil on average annually, or about a 5-6% supplement for K-12 spending, Gartner said. "I would not that consider that a windfall of transformative money."

Cardona says 'sustained effort' possible

However, the education secretary remains hopeful. "We finally realize how, after this pandemic, we cannot go back to how it was before," Cardona said, "so I'm hoping to see a sustained effort not only with the American Rescue Plan funds, but also with the president's budget that's put forward, and hopefully the economic growth that our country's going to experience."

A sustained effort is what superintendents have called for since the passage of the federal relief package in March. "It would be good to know ahead of time that this funding is going to be recurring at least to a certain point so that we know how to spend and plan to make this happen," Elie Bracy, superintendent of Portsmouth Public Schools in Virginia, said when ARP first passed.

At the time, Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Virginia), who serves as chairman of the House Committee on Education and Labor, said funds provided under the emergency packages have been "exceptional" and will be difficult to continue, especially considering the number of lawmakers who don't think additional funding is necessary. For multiyear funding to be on the table, education leaders must provide proof the relief expenditures have "made a difference," he said.

And on the state level, legislatures may also use districts' current spending decisions as a litmus test of whether states should increase their own share of education funding, Gartner warned.

But in education, change can require years of sustained interventions and may not become evident immediately. "Outcomes significantly lag funding investments," Gartner said. "Many of these things will take a generation to show real impact."

In the meantime, Cardona said educators must find "what's giving us the best return on investment in terms of making the experience of our students better" — something educators have had to do in the past — and prioritize those initiatives while cutting less impactful investments.

Perhaps the most critical priority in state plans that will yield a high return on investment, Gartner said, is universal pre-kindergarten, as that has the potential to boost low enrollment and bring dollars back into districts.

"This is a reckoning that has been coming for a really long time," she added, "because in the past several decades the world has changed so dynamically, and our education system really hasn't caught up to it."