McSwain Union Elementary School District in Merced, California, has been through about every COVID-19-era learning and teaching format available this school year: all-remote; only staff on campuses; and small student cohorts on buildings.

Just as the two-school, K-8 district got approval to invite all students back to campuses for face-to-face instruction in a hybrid format in late fall, a rise in community transmission rates threatened to force everyone back to remote learning.

At the same time, the state and the Merced County Department of Public Health were identifying school districts to pilot on-site rapid COVID-19 antigen testing programs under a program titled Safely Opening Schools. McSwain Union’s Superintendent Roy Mendiola, eager to keep his schools open, got the school board's approval to participate in the pilot.

By mid-February, the school system had provided optional testing for all staff and began a pilot to test a small number of students. Mendiola said the startup work to implement a testing process in such a short time was “overwhelming,” but that the meetings, paperwork and planning have been worth the effort.

“There is a peace of mind that comes with our surveillance testing that is simply not possible with all of the other protocols that we have implemented,” Mendiola said in an email.

School districts across the country are looking to add or expand COVID-19 testing that could identify asymptomatic staff and students as another layer of prevention from widespread outbreaks in buildings. The continual process involves multiple partners, funding sources, access to tests, a well-thought-out and secure testing procedure, and lots of administrative time, say those experienced in the operations.

“I think efficiency is so important because one of the underappreciated aspects of testing students in a school is the labor,” said Dr. Blythe Adamson, affiliate professor at the University of Washington in The Comparative Health Outcomes, Policy and Economics Institute and advisor at Testing for America. “[Access to tests] doesn’t solve all of these challenges if there's not administrative staff at the school who can drop every other obligation they've been doing to then run all of these tests that take time.”

Testing interest on the rise

Interest in repeated COVID-19 testing on K-12 campuses is increasing as the pandemic nears the one-year mark and administrators look for ways to mitigate the virus’ spread in schools.

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had previously not recommend universal testing of school staff, it has issued consideration for schools regarding testing. A Feb. 12 FAQ from the CDC also offered guidance for school operational plans based on whether they have diagnostic screening at individual student and staff levels.

That latest CDC guidance emphasizes five mitigation strategies to reduce spread in schools:

- Universal and correct use of masks.

- Physical distancing.

- Hand washing.

- Cleaning.

- Contract tracing.

If strict adherence to mitigation efforts are followed, schools could stay open for face-to-face learning, even in localities where community transmission rates are higher, the guidance said.

A U.S. Department of Education handbook, also released Feb. 12, reiterated the CDC’s mitigation recommendations and said testing and vaccinations can be used as additional precaution strategies, but that they should not be prerequisites for the safe reopening of a school. Schools testing students must also comply with privacy laws, such as Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Protection of Pupil Rights amendment, the FAQ said.

Several large school districts, such as New York City Public Schools and Los Angeles Unified School District, are regularly testing students and staff, according to their websites. A RAND Corp. study, released in January, found hundreds of public and private K-12 schools were using COVID-19 testing, and most “early adopters” were in states that had distributed BinaxNOW rapid antigen tests from the federal government.

Adamson predicts testing will expand as more school systems open in-person learning options. “We expect there to be an increase in administrators’ interest and demand for knowledge about how to implement a testing program because many have not had the opportunity to try yet,” she said.

About 60% of U.S. schools are offering some form of in-person learning, according to CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky.

To help schools navigate this developing situation, Testing for America, in conjunction with The Rockefeller Foundation and the Skoll Foundation, released an 87-page playbook for COVID-19 testing in K-12 schools that includes practical advice for preparing, designing, launching and maintaining a testing system based on individual school circumstances.

For example, the playbook offers ideas for securing financial support and methods on how to choose a test that reveals either active or past infections. Also in the playbook are stories from communities that have implemented a school-based testing program, such as Tulsa, Oklahoma, which prioritized its testing programs for schools located in areas with high hospitalization rates.

Chiefs for Change has additional resources, such as a project planning workbook, case study examples and interactive tabletop exercises, that align with advice provided in The Rockefeller Foundation's playbook.

Pilot built on partnerships

It was just a few weeks before the winter break in December when Mendiola got a call from the state and county health departments about the COVID-19 SOS testing pilot, which leaders wanted to start on a small scale before the break. Mendiola said he was eager to have his district participate in order to shorten the time between when a person was suspected of having the virus and when test results were returned.

A quicker turnaround time for test results meant his schools could react more quickly with quarantining and contract tracing if there was a positive case, he said.

When Mendiola talked to the school board and staff about the potential for the pilot, he admitted he didn’t have many details but that the project seemed promising. “The fact that it was a pilot, I operated on a lot of a lot of faith that this was an important project and it was, you know, the right thing to do,” said Mendiola, who also consulted the district’s attorney about the pilot.

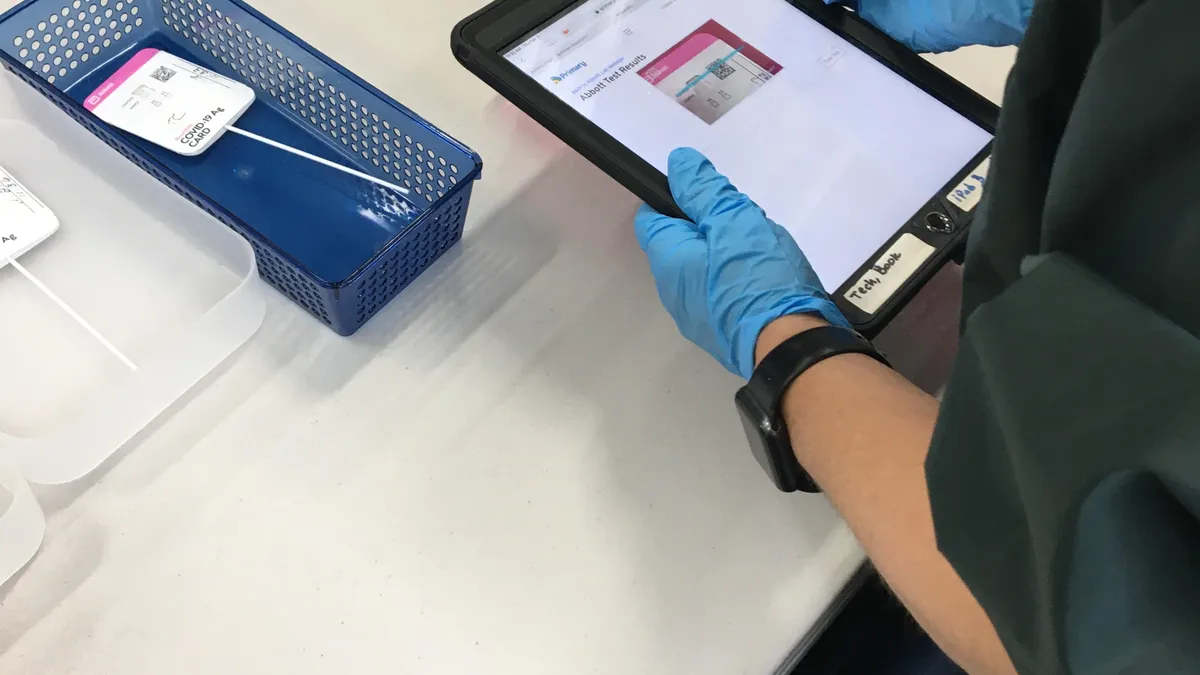

Mendiola worked with a team that included state and county health leaders, officials from the Public Health Institute who coordinated training and paperwork for the pilot, and Primary.Health, which managed the web-based platform for organizing testing logistics and information.

After email exchanges and many video conference calls, the team conducted a pre-pilot walkthrough that allowed people to use BinaxNOW rapid antigen tests to self swab their nasal passages and receive results in 15 minutes. The pre-pilot continued over the winter break, and about 25% of staff plus a few school board members elected to participate.

When schools reopened after the break, the district continued the pilot and made adjustments, such as the location of testing and correct handling of test kits, based on what organizers learned worked well. Mendiola would video conference with the pilot’s partners while walking through the different testing stations so health experts could offer feedback on best practices. Staff from other districts have also visited the McSwain Union testing site to learn about the process, he said.

Now, two months later, there is an 80% participation rate from staff who are offered the testing twice a week, and the district has begun a pilot testing program for students. Testing for students is optional with parental consent and is being planned for once a week, Mendiola said.

According to Dr. Lynn Silver, a program director at Public Health Institute, funding for the McSwain Union testing pilot was provided through federal stimulus funds and the California Endowment, a nonprofit that aims to expand access to affordable, high-quality healthcare.

The test kits were pre-purchased last summer by the federal government from Abbott, the developer of BinaxNOW tests, and distributed to states. For rapid testing, the state supplies the test kits to schools for free, said Primary.Health's Senior Vice President Sunshine Moore in an email. Primary.Health has multiple pricing models to accommodate budgets for large and small school districts, customizable for each district's needs, Moore said.

Mendiola said he expects to test students and staff through the end of the school year at no expense to the district, aside from the staff time and personal protective equipment needed, such as gloves.

Silver said the pilot’s organizers — referred to as a learning collaborative — discovered a lot from McSwain Union’s early participation in the pilot, which includes nine other districts. “We’ve been developing the training materials for other districts based on learning from the first few sites,” Silver said.

The learning collaborative also has regular meetings where organizers and participant school districts share information and lessons learned. “Everybody's learning from everybody's experience together,” said Silver, adding that Public Health Institute is planning to make school-based COVID-19 training materials publicly accessible on its website.

Mitigation efforts still needed

One important message the organizers convey is testing programs should not give schools a false sense of security, and other COVID-19 mitigation efforts also need to be taken seriously even while COVID-19 testing is taking place.

“What the SOS program is doing is really developing clear and easy to follow methods for on site rapid screening that can complement masking and social distancing and other school measures and give families school staff and teachers greater confidence in the safety of in-person learning,” Silver said. “We need to learn very quickly to make these type of tools available on a larger scale rapidly to help as many schools as possible to reopen more safely.”