Like many districts nationwide, the Northwest R-I School District in Missouri faced a surge of COVID-19 cases in fall 2021 that worsened an already growing labor shortage.

As few people were applying for open positions, an idea emerged to hold a job fair to gauge interest and hire high school juniors and seniors for custodial and aide positions, said Mark Catalana, the district’s chief human resources officer. Initially, the district hired nine students, a number that eventually resulted from the fair. That has since expanded to nearly 20, he said.

The roles students undertake at Northwest R-I range from cleaning up around school buildings and helping oversee elementary students in before- and after-school programs to meal prepping and cleaning the kitchen for school meal programs. Catalana said the district coordinates with students on their schedules and is flexible according to their needs.

Typically, the students had previously worked weekend jobs with longer hours, such as fast food restaurants, he said.

“Working for a school district, I think it’s a much more pleasant environment, it’s close to home and I think the parents like it that way too,” Catalana said. “It’s a good situation for them to be in.”

While the nationwide teacher shortage is widely known, noninstructional positions are also facing similar troubles in K-12. A National Center for Education Statistics survey found 49% of 670 public schools reported at least one nonteaching staff vacancy in custodial, nutrition and transportation staff as of January 2022.

Potential to inspire future teachers

District administrators are finding that paying students to fill nonteaching positions, particularly in student-facing jobs like before- and after-school care, can help students figure out if they want to work in education moving forward. In a way, the strategy to address staffing shortages can also help recruit future teachers, too, they said.

Northwest R-I has a grow-your-own teacher pipeline program, and the district is encouraging participating students to consider working with younger children in the before- and after-school programs. Students hired to do so are supervised by adults, Catalana said.

The practice of hiring students, which resurfaced in light of COVID-19, is not new.

About eight years ago at Bancroft-Rosalie Community Schools in North Dakota, administrators also struggled to find enough community members to work for the small, rural district’s after-school program overseeing 50 to 60 students.

It became difficult for only three or four staff members to handle on their own, said Jon Cerny, the district’s superintendent.

“Adults were saying, ‘We can’t do this, you got to get somebody,’” he said.

That’s when Cerny decided that he would start hiring several high school students to lighten the load for staff working after school. Students who work in the program must receive a paraprofessional certification, which the district pays for, he added.

Students are able to develop leadership and communication skills as they lead activities with small groups of children, he said. Responsibilities can include communicating with parents during pickup times, helping lead clubs, tutoring children, and monitoring younger students on the playground.

“It’s really kind of a work-based learning experience for them,” Cerny said. “Because they discover, ‘Do I like working with kids? Do I want to be a teacher?’”

Does it work?

Since he began the student employment program nearly a decade ago, Cerny said he’s starting to notice former participants pursue education careers.

“We’re starting to see now that some of those kids who’ve been working are interested in coming back and working for us, if we have openings,” he said. “It’s really been a good thing for us.”

Depending on students’ hours, it typically takes about three students to fill a full-time position, but that has made a difference at Northwest R-I, Catalana said.“It’s helped us tremendously,” he said.

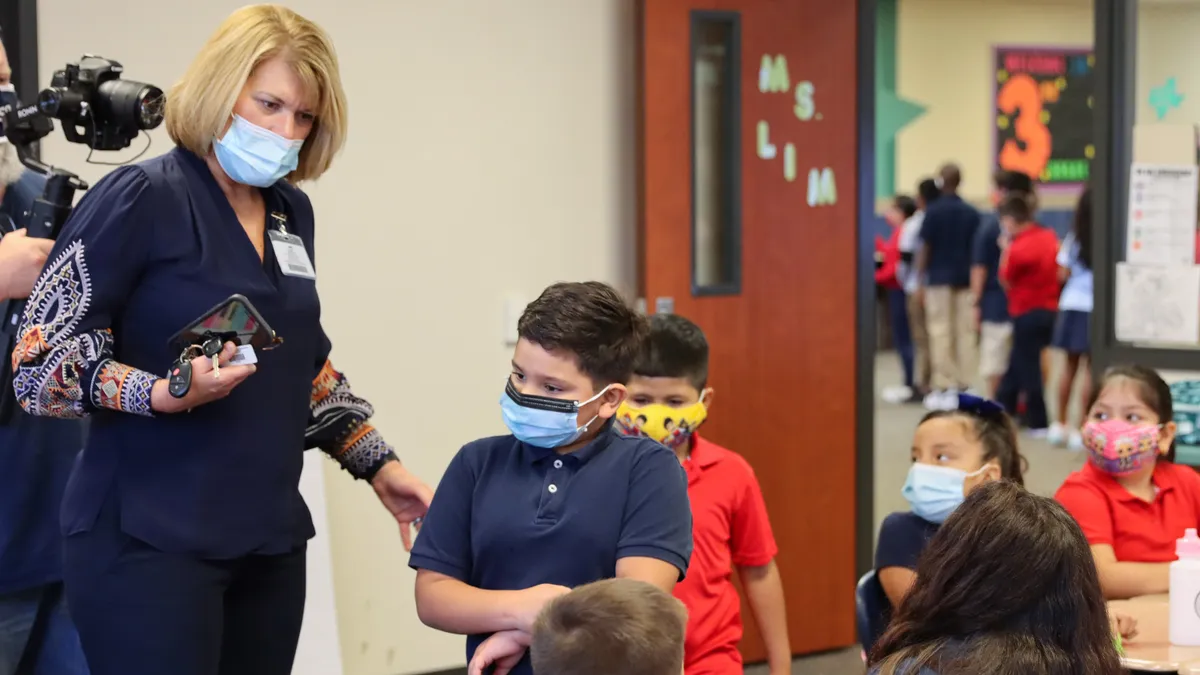

Last fall, Oakland Unified School District in California set up a Scholars in Service program using federal COVID-19 relief funds to fill staffing needs with students, said Greg Cluster, work-based learning coordinator for OUSD. Through the program, the district hired 38 high school students, who earned $15 per hour for various roles, Cluster said.

Students can intern in elementary school classrooms with teachers, help repair school technology, or assist with administrative duties in the district, he said.

Additional administrative support from high school students in front offices helped free up administrators to complete other tasks that were difficult to find staff for, such as contact tracing for COVID-19 in schools, Cluster said.

“There was a whole lot more work all of a sudden, because schools became key … parts of the public health apparatus,” Cluster said. “But that didn’t come with any additional staffing.”

The Scholars in Service program also helped ease working conditions for school staff when students were hired to monitor the school’s copy room and fix paper jams or other equipment issues, he said. On top of that, some students were trained to do basic Chromebook repairs, helping to address a longstanding need, Cluster said.

OUSD schools want to continue the program, but Cluster said they don't know yet if funding will be available from the central office. Schools that want to keep hiring students will have to consider using their own discretionary dollars if they do so, he said.

“I think schools are going to keep this alive anyway,” he said, “even without some of the one-time money that was available this year.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards