Shawn Bush was earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology and planning to become a school counselor when an email caught his attention. As a paraprofessional at Leo Politi Elementary School in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), he was receiving an invitation to become part of the district’s STEP UP and Teach program, which provides financial support and mentoring for those who want to become full-time teachers in hard-to-fill areas, such as special education.

“As I was working with children, I saw the need,” says Bush, who left an advertising and marketing career to enter the education field. “I realized it was meant to be.”

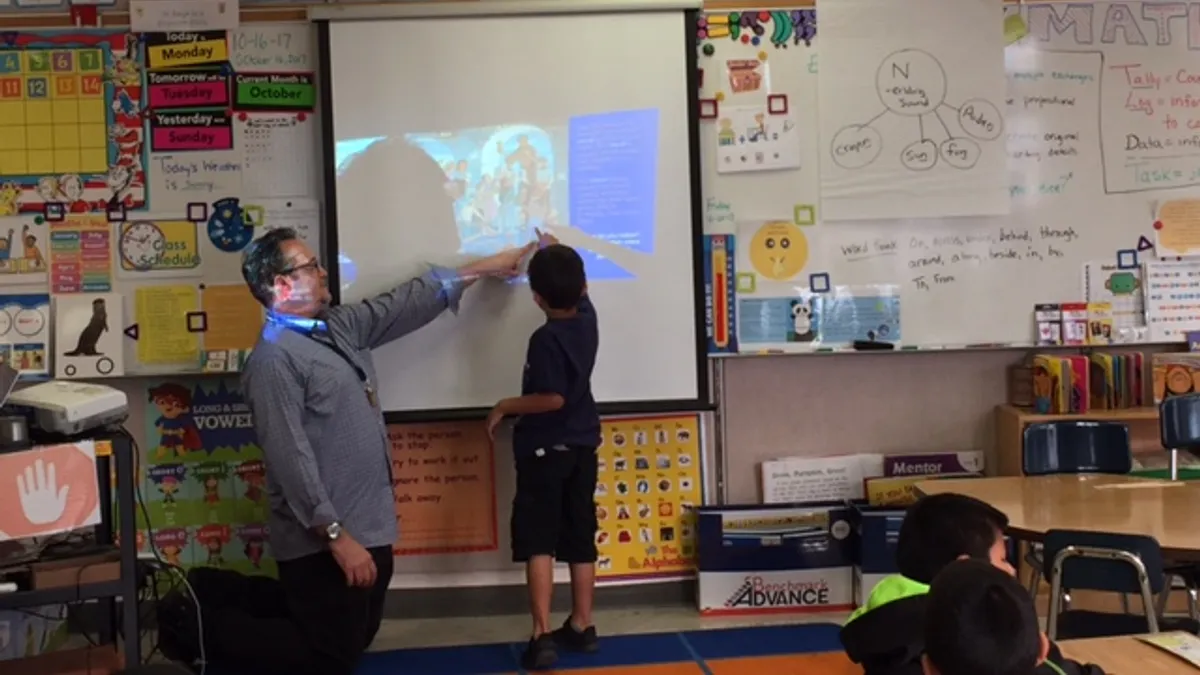

Now, when he kneels down to help the students in his multi-age special education class write words about what they’ve drawn on their papers or leads them into the office to see artwork painted by the school’s namesake, he’s building on a foundation he already created when he taught some of the boys in small groups as a classroom assistant. “I already had a relationship with them,” he says.

He knows which students can accurately continue patterns and recognize number groupings in their heads even if they aren’t very verbal, and he sees how the youngest transitional kindergartners in his class learn from the 2nd graders, even in an environment in which students have a hard time staying in their seats.

“The good news is that every day is different, and the bad news is that every day is different,” he laughs.

Recruiting those who already have classroom experience as paraprofessionals into teaching positions has become one of several strategies states and districts are using as the demand for teachers in specific areas grows more severe.

“They’re already working in our system and a lot of time our paraprofessionals were LAUSD students. They have ties to the community,” says Bryan Johnson, the assistant director for Certificated Recruitment, Selection and Credential Services with the district, which started STEP UP and Teach three years ago.

In the first year, 150 paraprofessionals enrolled in the program, which provides up to $4,800 in tuition reimbursement, professional development and guidance from a mentor as the candidates take on more teaching responsibilities in classrooms and work toward their degree. This year, 260 candidates are in the program, and over 100 have graduated and now have their own classrooms.

“The big thing with getting a teaching credential is that there is a lot of red tape,” says Gwenda Cuesta, a specialist with the program. “We sit down with them and say this is where you are, what you need to do and when you need to do it.”

Almost all states report special education teacher shortages

Even during the recession, when there was an oversupply of elementary educators and many districts were laying off teachers, there was still a need for special education teachers, explains Donna Glassman-Sommer, the executive director of the new California Center on Teaching Careers. With funding from the state Commission on Teacher Credentialing, the center will lead a campaign to attract people into teaching and work to match candidates with preparing programs and districts that fit their interests. Now with fewer people entering the field and those who stayed in the classroom feeling that now they can afford to retire, the needs are even greater.

Research conducted by the Palo Alto, CA-based Learning Policy Institute (LPI), which has brought attention to the teacher shortage issue in California and nationally, shows that only 36% of California’s special education teachers during the 2015-16 school year had a preliminary teaching credential, while the rest were working as interns or with permits or waivers.

Nationally, almost all states report shortages of special education teachers or specialized instructional support personnel, according to the National Coalition on Personnel Shortages in Special Education and Related Services. The organization lists “insufficient funding for incentive programs designed to entice new graduate students and support them as they gain professional training” as one of the reasons for the shortages.

Anne Podolsky, a researcher and policy analyst with LPI, says programs such as LAUSD’s address some of the financial reasons why people either don’t pursue or don’t complete teaching credentials. Young people, she says, are often unwilling to take on debt, and those paraprofessionals who already have families may have put off completing their degree because of other commitments.

Cuesta says her team learned that for some candidates attending community colleges, affording tuition wasn’t a problem because they already had grants, but the cost of textbooks was a barrier, so now they can get assistance with those expenses, as well as with fees for tests and test preparation programs.

Being ‘seen with fresh eyes’

As Johnson of LAUSD says, many paraprofessionals come from the communities where they work, which in diverse school districts can help to increase the numbers of educators who share the same race, ethnicity and home language as the students they serve.

“Students stand to gain quite a bit from paraprofessionals,” writes Amy Auletto, a doctoral student in educational policy at Michigan State University. “Due to their familiarity with the local community, higher retention rates, and racial diversity, these individuals have the potential to benefit students in more significant ways than they are in their current roles.”

Luis Ochoa, principal at Politi, says Bush’s transition into leading his own classroom has been smooth and that Bush was fortunate to gain a full-time position not only in the same school where he was a paraprofessional, but also in the same classroom.

“We constantly are encouraging the rest of the paraprofessionals to participate in the program,” Ochoa says.

In Bush’s case, already knowing the students and parents has been a benefit. But Glassman-Sommer adds that sometimes when former paraprofessionals begin working alongside teachers who knew them as classified personnel, they don’t always feel confident in their new role. That’s why, she adds, it sometimes benefits these new teachers to work in a different school or in a different grade level so they can be “seen with fresh eyes.”

She adds that compared to new graduates and those who have switched careers to enter teaching, paraprofessionals tend to face more challenges when transitioning into full-time teaching positions. These can include juggling course loads at night while working during the day, lacking adequate child care for their own children, or having other family responsibilities.

Podolsky adds, however, that because mentoring and support programs have been seen as a key to retaining teachers in the field, programs such as STEP UP and Teach can not only fill immediate needs for teachers but can also keep teachers in the profession for a longer period of time.

In his transition to full-time teacher, Bush says the individualized education program (IEP) process was especially challenging. “You want to make sure it’s absolutely perfect,” he says. He adds that the district-provided training in Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports has helped him create incentives in his classroom for staying focused and to recognize when it’s time to move on to another activity. “I use those techniques every day.”

Still, Glassman-Sommer says that recruiting paraprofessionals into teaching should be only one strategy school districts are pursuing to fill vacancies in high-need areas.

“With the amount of openings that we have and the reduction of individuals going into teacher preparation programs right now,” she says, “there really needs to be a mass campaign about going into teaching.”