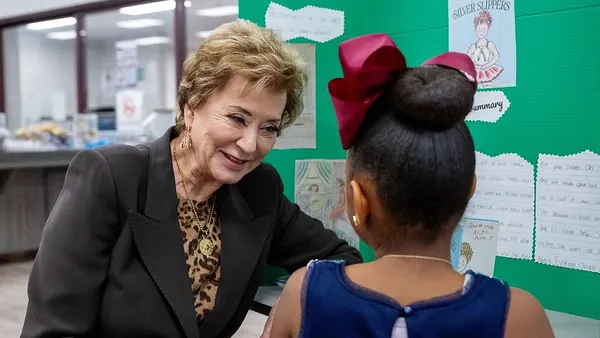

When Elizabeth Brown took over as principal following a 2018 school shooting at Florida's Forest High School, she thought her community had made plenty of progress in its recovery: The room where the shooting took place had been repurposed, parents seemed to trust her with the school safety plan, and Brown had gotten the hang of working around students' trigger points.

That was until, several months later, a textbook fell from the second story of the school with a piercing boom. All the students — over 200 who had been in the hallway between class periods — immediately ducked to the ground.

"In that moment, I realized the residual trauma from the shooting is still very real," Brown said. "Healing was a marathon, not a sprint."

In that marathon, students were at different mile markers: Some students were able to quickly bounce back from the triggering noise, while others took longer to recover.

Recovery following the trauma of a school shooting is not uniform — it varies by community, from school to school, across student subgroups and even among individuals. It is also impacted by factors like the availability of school counselors, barriers to accessing mental health support and pre-existing traumas.

Family structure, how different communities grieve, and past experiences with gun violence and law enforcement can all inform this process, as well.

Because of these differences, measures commonly adopted by schools nationwide in response to school shootings — like doubling down on school police or bringing in grief counselors — should be tweaked or reconsidered to fit the needs of Black, Hispanic and immigrant communities, according to school trauma, crisis and security experts.

Bringing in community 'brokers'

Robb Elementary School, for example, is 90% Hispanic/Latino, a student subgroup that is more likely to experience stigma around mental healthcare. Robb is also 87% economically disadvantaged, according to 2022 school district data. Up until the 2020-21 school year, it had one full-time counselor for 538 students, according to U.S. News & World Report.

Schools with thin resources and stigmas to work around should consider tapping into help from their community leaders, said Gerard Lawson, a licensed professional counselor who helped coordinate the response to the 2007 shootings at Virginia Tech. Lawson, who specializes in crisis management, is also a professor at Virginia Tech's School of Education and former president of the American Counseling Association.

"We want somebody that can open that door for us and be able to broker that we actually do have something to offer," Lawson said.

Even with the availability of counseling services, pre-existing traumas and cultural differences can make recovery an even more complicated process.

"What are the natural supports for that community that we can engage," Lawson said, "to be sure that when we are done with the immediate sort of interventions — the stuff that needs to take place as a crisis response — that there's a longer term crisis recovery process?"

Increasing law enforcement not for everybody

As part of that crisis response, many lawmakers and school leaders have discussed increasing law enforcement and security in schools.

However, this option may not be suitable for all students, students' families have pointed out. Black and Hispanic students are already more likely to be in schools with police presence — which is associated with increased school arrests — than their White counterparts.

"Schools cause trauma. And not just through school shootings, but in a myriad of ways, especially for historically marginalized and systematically oppressed groups," said Addison Duane, a former elementary school teacher with a Ph.D. in educational psychology and now a professor at Wayne State University. "And I think that, in the wake of something as horrific and preventable as a school shooting, the trauma compounds."

Duane’s research and expertise includes trauma and racism in school.

Research from 2020 on disparities in school safety measures, for example, suggests African American students are more likely to report being within eyesight of a security camera or engage with other authoritarian forms of school security. Authoritarian forms of security cited by the research also include locked gates and metal detectors.

Matthew Cuellar, assistant professor at University of Alaska Anchorage's School of Social Work and co-author of the study, wrote that African American "youth who are preoccupied over being monitored or worried about their external environment may be demonstrating some anxious tendencies" that could lend to less engagement in academics.

In that same study, researchers also suggested Hispanic students were more likely than their peers to walk through locked gates and less likely to engage with proactive forms of school security like mediation training.

Ensuring services are accessible, culturally reflective

African American and Hispanic students are the same subgroups that have reported barriers to accessing mental health services, including racial differences between counselors and students and mental health stigmas.

To Cuellar, this suggests that providing accessible mental health care in schools requires more than just making counselors available.

"It's a little bit more nuanced than that," Cuellar said. "The idea is that if we put mental health [services] in schools, we have to think about how students are going to access them, how can we ensure that they're culturally appropriate?"

A thorough needs assessment — including assessing school connectedness, school climate and student and staff perceptions of safety — could help answer these questions, said Cuellar.

"What might be impacted by adding another metal detector or adding an armed security guard?" Cuellar said, addressing things administrators should consider before making such decisions. "Every school is individual, every school is different."

And still, for Brown, the Florida principal, the vicious cycle of fallout from school shootings continues. Although the classes directly impacted by the 2018 shooting in her school have since graduated, their siblings who were in lockdown elsewhere in the district at the time have entered high school with their own traumas. The trauma also lives on in their parents.

"So now it's [recovery] is a different approach, but it's still a priority," Brown added.