This month, the U.S. Department of Education began accepting applications for a pilot program in which seven states, or state partnerships, will be approved to implement “innovative assessments,” which can include performance assessments.

Since the program was announced as part of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), interest in and discussions of how to plan and best use performance assessment has increased, and other states are looking to New Hampshire for guidance on how to create, validate and spread teacher-designed assessments across multiple districts.

The New Hampshire Performance Assessment of Competency Education (NH PACE) initiative, which was allowed under a 2015 U.S. Department of Education waiver to replace some annual standardized tests with performance assessments for accountability purposes, is what inspired the ESSA pilot.

“We’re just creating fantastic assessments in classrooms that make sense for kids,” says Ellen Hume-Howard, the executive director of the New Hampshire Learning Initiative and the former curriculum director of the Sanborn Regional School District, one of four original PACE districts covered by the waiver. “We were out there proving it, collecting the data and giving some credibility to this approach.”

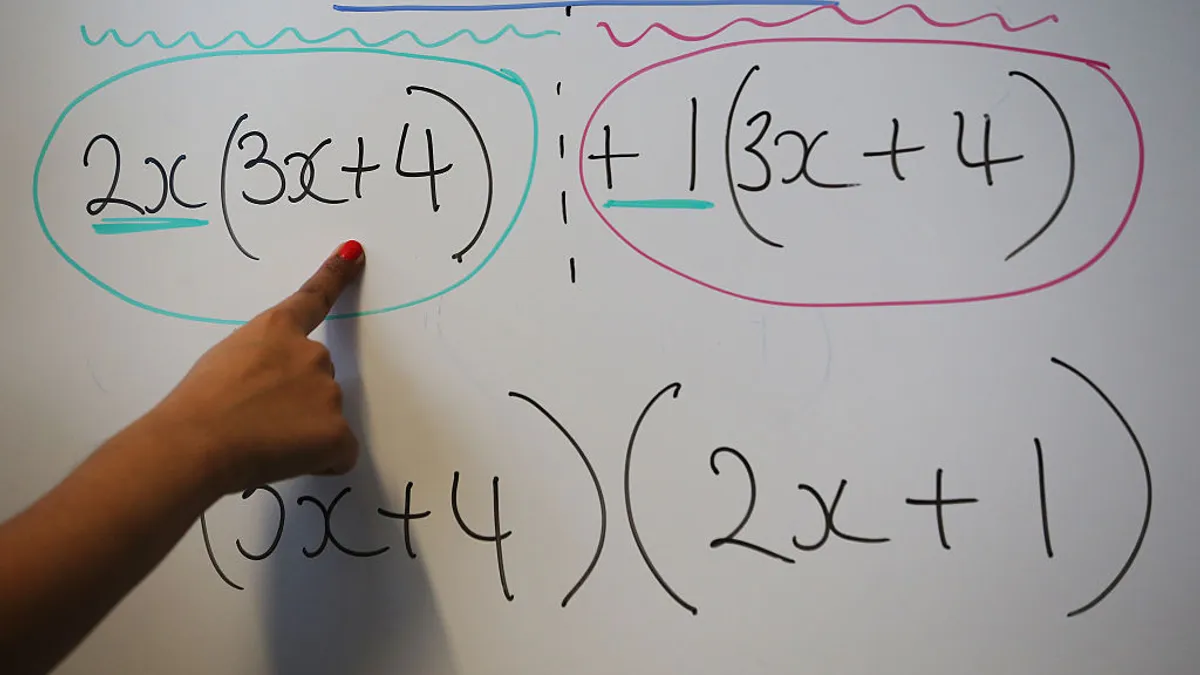

Now, 25 districts in the state use performance tasks — such as an essay, a science experiment or a math project — for the bulk of their assessments and only give the Smarter Balanced assessment once in elementary school, once in middle school and the SAT in high school.

“We’re not against testing,” Hume-Howard says. “We are happy to embed standardized testing, but let’s make it make educational sense.” Third grade, for example, when students are making that “reading-to-learn” transition is a good time for a “standardized measure,” she says. Eighth grade, before students transition into high school is another logical point, she says.

Creating assessments that don’t ‘detract’ from learning

While performance assessments are not new, interest in using them as a replacement for standardized, multiple-choice tests has increased, in part because state tests “played an outsized role in schools” under No Child Left Behind, Robert Rothman, a senior editor at the National Center on Education and the Economy, and Scott Marion, the executive director of the Dover, NH-based National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment, wrote in a 2016 Kappan article. Alternative or performance assessments, they wrote, “could support student learning, rather than detract from it, as critics charge current state tests do.”

In addition, many policy decisions have been based on end-of-year assessments that are not connected to what students learn throughout the school year, says Chris Minnich, the former executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers and now the CEO of NWEA, a nonprofit assessment organization.

“In most states, end-of-year activity is assuming that we know nothing about these kids,” he says.

Better preparation for college

In addition to New Hampshire, officials from Arizona, Hawaii and Louisiana have said they plan to submit an application for the ESSA pilot program. But districts in several other states are also exploring how performance assessments might be integrated into their testing systems.

The Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment, for example, involves six school districts in which teams are learning how to design performance assessments and train teachers how to score student work. Some of the assessments generated through the initiative are now being piloted across the districts, as well. The state is working with the Center for Collaborative Education, which has created a Quality Performance Assessment framework and leads schools and districts in creating performance tasks as part of their assessment systems.

At a recent gathering of educators and assessment experts involved in the initiative, Marissa Roque, a 7th grade teacher from the Somerville Public Schools — one of the districts involved in the consortium — spoke about how multiple choice assessments often don’t capture what her students know about a particularly complex topic.

“How do you assess the impact of something as large as apartheid with a quiz?” she asked. “I can see that they understand the social impact in South Africa, but it doesn’t always show up in their quiz grade.”

In California, the Learning Policy Institute recently held a webinar for those interested in learning more from performance assessment pioneers, and plans to hold another one on May 17.

“We’ve been doing this since 1998, and we’ve had a lot of success with students once they go on to college,” Ann Cook, the co-director of Urban Academy Laboratory High School in New York City and the executive director of the New York Performance Standards Consortium, said during the webinar. “They have a lot of academic skills, as well as the ability to ask for help, to know how to get help, and how to use it.”

Paul Leather, formerly of the New Hampshire Department of Education and now the director of state and local partnerships for the Center for Innovation in Education in Lexington, KY, said it’s important to recognize that not all performance assessments are the same. Some, which are more like portfolios, are intended to cover an entire course, semester or even multiple courses, while others are tied to specific instruction or given at the end of a unit.

In the Oakland (CA) Unified School District, performance assessments began about five years ago with a senior project graduation requirement, but the standards students were expected to meet varied from school to school, explains Young Whan Choi, the manager of performance assessments for the district. “Teachers and students were not happy about this,” he said during the webinar.

Schools and leaders decided that students would be required to complete a research project that included a field research experience, such as a survey or a focus group. They also created a rubric for schools to follow. Now, as more schools have adopted the requirement, almost 70% of seniors are being assessed through that project, and Choi believes the next step if for the district’s school board to adopt a policy that would apply to all schools.

“This process was really led with teachers at the center,” he said.

And even though New Hampshire is considered a leader in this field, more than half of the districts in the state are still not part of PACE. Hume-Howard notes that there are some characteristics among schools and teachers that can make the transition to performance assessment smoother.

First, those that already have professional learning communities, in which teachers regularly collaborate and plan together “definitely have an advantage,” she says. In addition, teachers had to be willing “to give up some things that they thought were getting the job done” in assessing students.

What they gain, she adds, is the freedom to give an assessment when they believe their students are ready instead of everyone taking a test on the same day. She says they also learn much more about their students than what they could get from a standardized test, and that students are less likely to experience the anxiety that they would before or during a typical exam.

“Kids don’t realize they are taking any kind of test,” she says, adding that parents are also supportive. “I don’t think I’ve met a parent who wants their kid to do standardized testing. They don’t see a lot of return on it.”

Minnich adds that even with traditional forms of testing, it’s important to have an assessment system that is more useful for teachers and reflects students’ growth. NWEA is currently working with the Nebraska Department of Education (NDE), for example, on its Student-Centered Assessment System, a “connected system of targeted assessments coupled with an increased commitment from NDE to professional learning opportunities for teachers,” according to a press release.

While performance assessment can be “an important part of an assessment system,” Minnich says, he adds that moving too far away from standardized testing “wouldn’t work either. We’ve got to get more balanced.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards