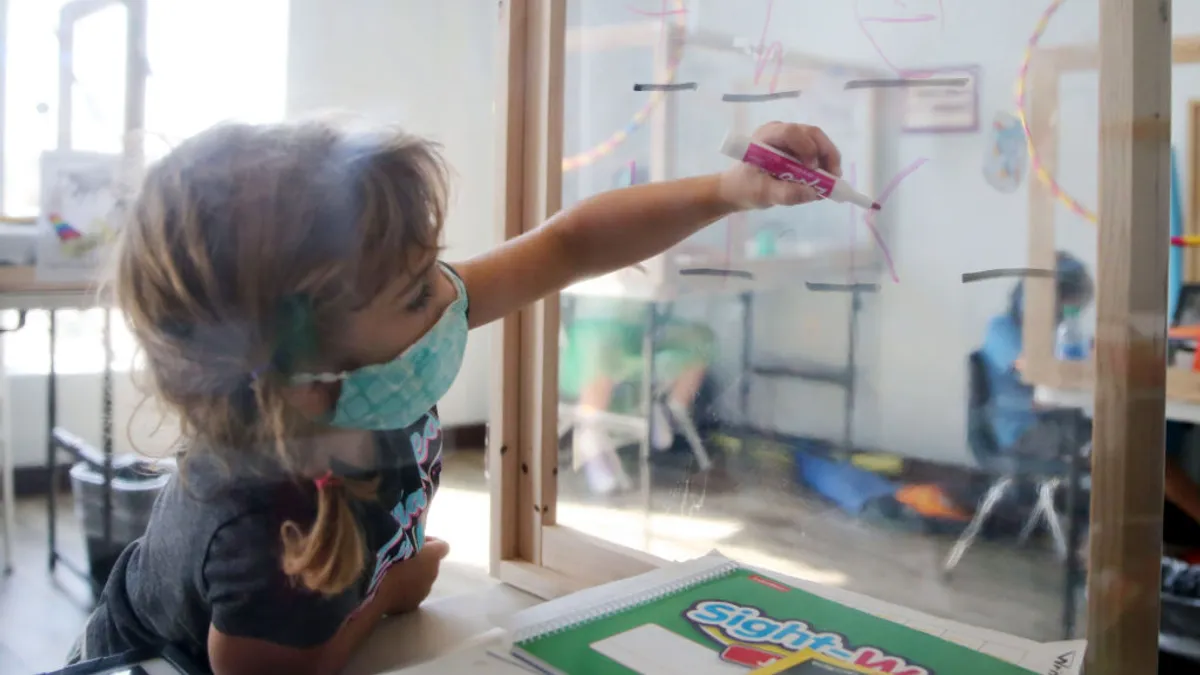

This article is the third and final installment of Expectations for ESSER, a series examining the implications of the federal government’s one-time, historic infusion of flexible funding to triage projects designed to blunt the impact of COVID-19 on schools. For the full series, click here.

Behind all the notable federal emergency pandemic aid investments like summer programming, school renovations and additional staff for academic and mental health supports lie hidden barriers district officials say are burdensome — but tolerable given how much federal money has flowed into K-12 schools.

There is confusion about compliance and reporting protocols, changing guidance, delays in accessing funding, and a stubborn and still-mysterious global pandemic in the driver's seat of decision-making.

There's also pressure to spend a collective $189.5 billion in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds quickly while still showing proof of a return on those investments and ensuring those improvements will sustain for years to come.

Some also fear that if school systems, which have begged for more funding for decades, can't show significant academic gains or other positive outcomes with ESSER funding, there will be political reluctance to provide large budget increases in the future.

There's already a skeptical audience.

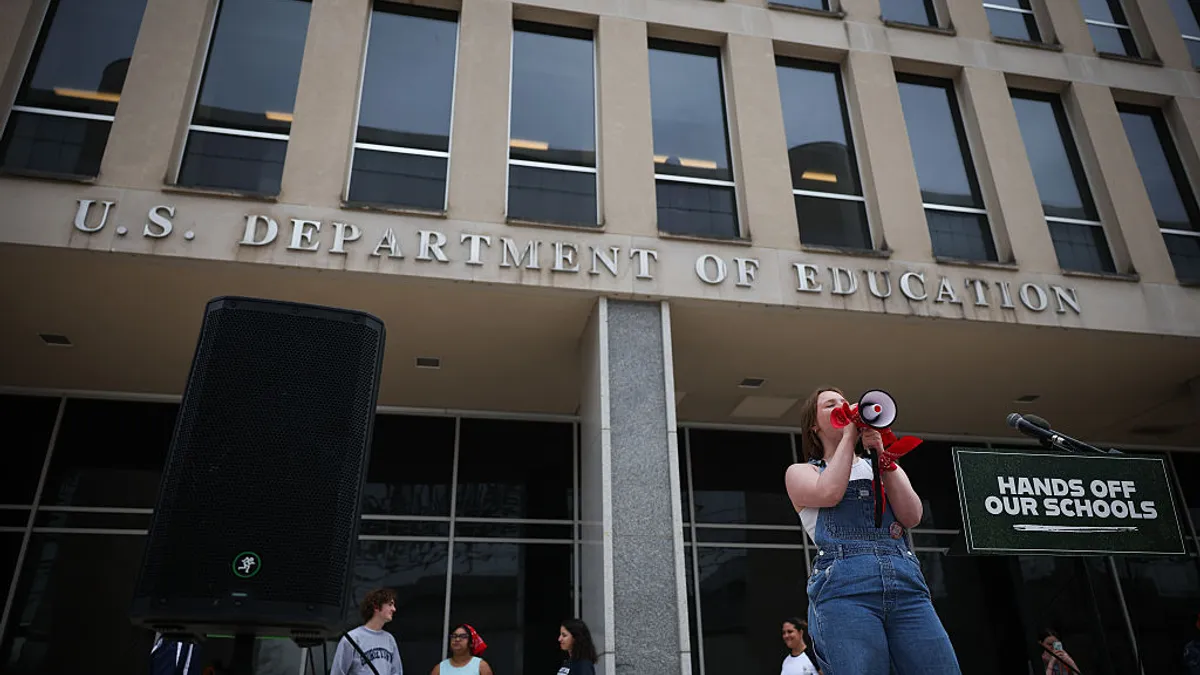

"Republicans consistently argued the proposed [American Rescue Plan] funding for elementary and secondary education was far too much and far too soon after a significant round of emergency aid for schools had just been enacted on a bipartisan basis less than two months before this debate," wrote U.S. Rep. Kevin McCarthy, House minority leader, and U.S. Rep. Virginia Foxx, ranking member of the House Education and Labor Committee, in a Jan. 12 letter to U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona.

The letter addressed a concern about ARP funds being spent too slowly, as well as concerns about money going toward "left wing ideological projects."

"Some schools are grasping at any project they can find on which to waste these taxpayer funds, including indoctrinating students and staff with racist and divisive ideologies," the letter continued.

Education leaders say otherwise. Their ARP spending plans have been carefully crafted with public input, are publicly accessible, and are based on reviews and data of specific needs in their districts, they say.

Joseph Ricca, superintendent of White Plains Public Schools in New York, touted what he called a collaborative effort undertaken by school systems and their partners to make every ESSER dollar count. School district and community leaders in his region meet virtually on a weekly basis to talk about approaches to overcoming challenges in providing meals to students, support for students with disabilities, safety precautions for sports teams and much more.

I'm very proud of this, as we look back, we never stood still. We always said, 'What's going to be in the best interest of kids? What's going to be in the best interest of this community?'"

Joseph Ricca

Superintendent of White Plains Public Schools in New York

All this leads to the question of whether this seminal moment in education finance history will produce the results some are aiming for, such as closing achievement gaps and ensuring equitable access to high-quality opportunities and school facilities. Or should this moment be more realistically viewed as a Band-Aid to keep schools from backtracking below pre-pandemic levels?

Evolving plans

States and districts have had to adjust strategies as COVID-19's delta and omicron variants forced schools to temporarily close again or to quarantine staff and students. As states adjusted set-asides for required uses of ARP funds, they had to amend their plans with the U.S. Department of Education, said Laura Jimenez, senior advisor at the Ed Department's Office of Elementary and Secondary Education.

States have their own rules for how and when districts should update their local ARP plans based on the significance of the changes, according to interviews with district leaders.

And because of COVID-19 variants and local outcomes data, plans are expected to adjust over time.

At the Nine Mile Falls School District in Washington, Claire Olson, director of business operations, said the district's spending plan morphed over time but stayed true to its main goals.

"I had to do numerous budget revisions in the grant itself just because things would shift," she said.

Districts are also looking at how best to blend ESSER funding with their annual federal grant, state and local allocations. School systems like Texas' Dallas Independent School District and New Mexico's Albuquerque Public Schools melded pre-existing strategic plans with their ESSER spending goals to align already developed targets with this significant one-time revenue source.

Many school systems are trying to stretch their ESSER dollars even as they face rising prices, supply chain issues, staff shortages and uncertainty about the health of annual budgets due to drops in student enrollment.

In some localities, ARP funding has been slow to reach districts, exacerbating the potential for a not-ideal situation of being under pressure to spend a huge bump of money in a short period of time, said Marguerite Roza, director of Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University. The fear is that this could create a fiscal cliff scenario, Roza said.

States and their districts had spent between 7.4% and 35.7% of their total ESSER allocation as of March 31, according to spending reports posted by the Ed Department.

ESSER I funding must be obligated by Sept. 30, 2022, and ESSER II funds by Sept. 30, 2023. ESSER spending outlays could extend to 2028, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Because of the flexibility districts have with ESSER spending, Roza and other researchers reviewing district spending plans see a variety of spending patterns. Roza says schools are, for the most part, spending ESSER money as the laws intended, which is to respond to and recover from the pandemic's impact on education.

However, some expenditures, such as hiring long-term staff, could cause disruptions when a district no longer has the funds to support those salaries, she said.

District leaders are "spending their money in ways that make it very hard to recover when the money runs out," Roza said. "When districts go through a reduction in force and do layoffs, it becomes all consuming and distracting for staff, for families, for administrators, for the public. It takes the eye off of focusing on students and what to achieve for students."

Staying compliant

As with any large infusion of federal funding, there's concern about waste and fraud. After the 2009 passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which pumped more than $98 billion into school systems in response to the Great Recession, the Ed Department's Office of Inspector General opened 218 criminal investigations and reviewed more than 140 allegations of whistleblower reprisals over the next five years.

The two biggest challenges with ARRA funding were oversight and monitoring, and data quality and reporting, according to a 2014 IG report. Using the experience from ARRA, the inspector general has created oversight protocols to help prevent bad actors from stealing ESSER funds.

The Office of Inspector General completed a number of pandemic relief aid reviews and have more underway. The office's long-standing policy is not to confirm or deny investigative activity and it does not share information about ongoing audits or investigations. It does discuss its completed work, said Catherine Grant, a public affairs liaison in the Office of Inspector General.

In addition to fraud oversight, the Ed Department has issued various guidance documents and hosted webinars to share best practices and district approaches for spending the ESSER funds.

According to a February 23 webinar, the Ed Department is conducting several levels of monitoring of ESSER grants:

- Targeted monitoring. This focused monitoring hones in on specific identified challenges. For example, the department held seven monitoring activities with grantees on cash management after unexpectedly large draw-downs.

- Comprehensive monitoring. This is a full programmatic and fiscal review of selected states based on a risk assessment. Indiana and Maine were selected in FY 2021 and Wisconsin and California were selected for comprehensive monitoring in FY 2022.

- Consolidating monitoring. This cross-program review looks at multiple federal education programs, including ESSER funding.

In a new approach, the Ed Department will also conduct quarterly monitoring reviews for every state focusing on a high-priority issue. Department officials and state leaders will discuss the state's progress, challenges and outcomes in spending ARP funds. In these reviews, the Ed Department asks about communications and outreach states have had with districts.

The quarterly reviews will also help identify promising practices that can be shared with other states and districts, as well as strategize support for challenges identified during the reviews, said an Ed Department spokesperson.

The first quarterly review, which focused on how states supported districts in reserving 20% of ARP funds for evidence-based interventions for learning loss, began at the end of April and will likely be complete by mid-June.

"Getting ahead of compliance issues is really important for us," said the Ed Department's Jimenez.

Each state will receive a determination letter outlining any compliance issues identified during quarterly monitoring. Those letters will be posted online once all reviews are completed.

Also under scrutiny will be how states and districts follow maintenance of effort and maintenance of equity rules.

Maintenance of effort — sustaining financial contributions to at least the same level at a determined point in the past — has different protocols under each of the three ESSER allocations.

Maintenance of equity — ensuring essential services are meeting the needs of historically underserved groups of students — applies only to ARP funding and only for the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years.

The Ed Department issued a final rule for maintenance of equity on June 8. Some say the final rule gives clarity to reporting requirements without putting additional burdens on school system staff.

But others still have questions about implementation and enforcement. It’s also unknown whether these efforts to hold school systems accountable to use pandemic relief dollars for equitable staffing and funding in high poverty schools will have momentum after the public health crisis.

Ivy Morgan, associate director for P-12 analytics at The Education Trust, hopes the provision enhances the set of tools educators have to ensure schools and districts — particularly those with high concentrations of students of color and students from low-income backgrounds — have the resources to serve their students. The Education Trust aims to close opportunity gaps that disproportionately affect students of color and students from low-income families.

The lasting impact

Balanced with all the ESSER challenges are the benefits billions of dollars are creating for school systems across the country, said Julia Martin, legislative director at Brustein & Manasevit, a Washington, D.C.-based law firm specializing in education, workforce and grants management.

"The amount of money, how quickly it went out, and just the really broad flexibility in almost every case is really helpful," Martin said.

When the last of the ESSER money is spent, school system leaders are hoping that not only will their schools have data to prove significant academic and social and behavioral gains and increased equitable access, but that the subtle benefits the extra federal funds brought — the expanded playground, the updated classroom lights, the school spirit events — will also prove they put the money toward building back a better school system.

"We had to make decisions based on the best information that we had at the time. And did we get it right all the time? Absolutely not. But I will tell you this, and I'm very proud of this, as we look back, we never stood still. We always said, 'What's going to be in the best interest of kids? What's going to be in the best interest of this community?'" Ricca said.

Many educators are also hoping this period of innovation is contagious and will spur voters and lawmakers to commit to more resources for schools even after the pandemic subsides. Public school advocates likewise hope the pandemic experience proved how vital public education is to the economy and the welfare of localities.

In the region around the White Plains School District, the momentum for collaboration between lawmakers, government agencies, community organizations, businesses, educators, parents and others — which really took off during the pandemic — will continue to grow, Ricca said.

"The public schools, they are the incubators of the American democratic experiment," Ricca said. "So supporting our public schools, making sure that every child across America has access to high-quality education and support is only going to further this experiment, and that's where we're at. We're focused on the future and making sure that all of our kids get out there into the world and make a positive difference."