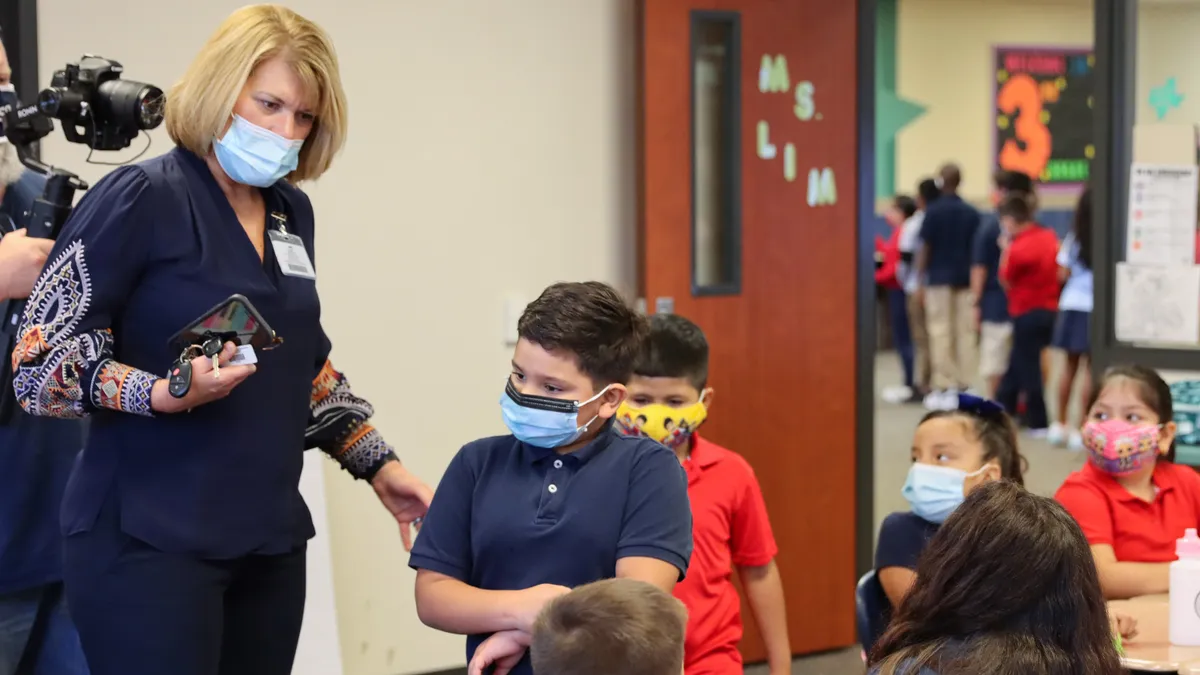

Kelly Carvajal-Hageman is director of instruction for the Seaford School District in Delaware.

As the director of curriculum and instruction for Seaford Public Schools in Delaware, I’ve encouraged the schools and educators with whom I work to become rebels — rebels for kids, that is.

For the last few years and through the trials and tribulations of the pandemic, Seaford Public Schools has been working to transform teaching and learning through the intentional use of high-quality instructional materials. As this school year ended, I reflected on just how far Seaford schools have come, against tough odds, and just how much is possible when educators, families and students remain committed to progress.

On a webinar hosted earlier this year via CurriculumHQ, a platform that shares free information and stories about the expanded use of high-quality instructional materials across the states, I had the opportunity to share concrete examples of the impact that high-quality curriculum and aligned professional learning is having on Seaford classrooms, bringing to life the findings from a recent report from the Center on Public Research and Leadership at Columbia University.

“Staying the Course” found Delaware districts that adopted evidence-based, peer-reviewed curriculum and provided teacher training centered on the instructional materials are reporting impressive outcomes.

The gains in student achievement are especially remarkable given their timing — when school systems across the nation, including in the First State, experienced declines due to pandemic-related disruptions.

Our good news in Delaware is that districts that have been dedicated to high-quality instruction are posting promising gains. Students at Lewes Elementary, for example, experienced declines at half the rate of peers across the state following the pandemic. At Allen Frear Elementary, student growth averaged 11 percentage points higher than peers across Delaware between 2021 and 2022.

Academic gains brought to life by classroom experiences

These data points are impressive, but of course they don’t fully reveal the impact this work is having in the classroom. Grace McCarty, principal author of the CPRL report, explained during the webinar that instructional materials do not “script” teachers or limit their craft — they provide the tools educators need and want as a foundation for their interactions with students.

“Because high-quality materials are guiding teachers to act as conversation facilitators as opposed to lecturers, this has transformed some classrooms that were traditionally more teacher-led or lecture-based to spaces where students are really leading their learning through conversations,” McCarty said. “Folks are seeing more joy and engagement from their students.”

In my role coaching teachers and school leaders, I’ve seen plenty that validates these findings. Seaford educators are more confident in their planning, instruction and interventions than ever before. They’re collaborating with their fellow educators, digging deeply into student data to find successes or areas in need of additional focus, and planning engaging lessons that are a world apart from the stereotypical, lecture-heavy instruction with which many of us grew up.

Best yet, our educators are able to genuinely commit to these tasks, because they’re no longer spending hours and hours every week hunting down and piecing together lessons, activities and student experiences.

And as McCarty highlighted, we’re seeing significant effects in classrooms. In addition to promising academic indicators, we’re hearing inspiring stories about student engagement in learning.

One math teacher at Seaford Middle School recently shared a success story with fellow educators from across the district. Their student, let’s call him Roger, had experienced difficulties in math classes for a number of years and, in this current school year, had expressed feeling far behind his peers. When discouraged, Roger tends to disengage in math.

This year, however, Roger has developed a new confidence in math and an apparent love of problem-solving. Following the end of a recent class period, Roger “did not wish to stop working when the bell rang to end class,” said his teacher. “He continued to research the problem, questioned others on what they thought was the correct method (outside of class) and even solved it.”

The key to unlocking Roger’s interest and success in math, according to his teacher, was better use of high-quality evidence based math curriculum. “The flexible groupings and new strategies implemented allowed Roger to feel success and be the leader. His engagement for two class periods (and at home) was phenomenal and encouraging to me."

Fortunately, states and school systems can learn from our journey in Seaford and other districts in Delaware.

Recommendations for advancing high-quality instructional materials

The virtual panel, which included perspectives from the Delaware Department of Education and Education First in addition to Seaford Public Schools and CPRL, provided a series of actions any state could take to improve their teachers' access to and usage of the best instructional materials for students. These include the following, which are taking place in several states:

- Providing districts with vetted lists of recommended, high-quality curricula.

- Supporting alignment of professional learning opportunities for teachers with district-selected instructional materials using state grant programs.

- Ensuring school systems can learn from one another by convening district and teacher leaders, creating opportunities for cross-district engagement, and informing local instructional decisions.

- Crafting and communicating a shared vision for the role and use of high-quality instructional materials, assessments and teacher training.

The success of this work depends on collaboration. State education leaders must be intentional in the ways they support and engage districts. Monica Gant, chief academic officer at Delaware Department of Education, explained, “In our role as a support agency, we work with districts and charters to ensure educators are shifting from initial adoption to skillful implementation of their instructional materials — and we are really intentional about that word ‘skillful.’"

This thoughtful approach is necessary to ensure districts see their state leaders as partners in the work rather than officials removed from realities of the classroom.

The need for the best materials, resources and tools for teachers and students is clear. Extensive research shows student achievement following the pandemic fell to the lowest levels seen in decades, with today's students facing lower prospective lifetime earnings and surging obstacles to fluent reading, numeracy, and higher education and career paths.

Delaware is leading recovery efforts by example in the best possible way: prioritizing and incentivizing use of rigorously reviewed materials, genuinely partnering with districts and schools, and staying the course on what they know is working, even in the face of extreme pressures like the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the end of five years of implementing high-quality English Language Arts materials and three years implementing improved materials in math, I can confidently say the journey is only getting smoother. “Staying the course” on our commitment to empowering educators and students with high-quality instructional materials is making the difference. The results should motivate all of us to be “rebels for kids.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards