Education policy is among the most controversial, often inspiring the most impassioned opinions of all of the federal policy areas.

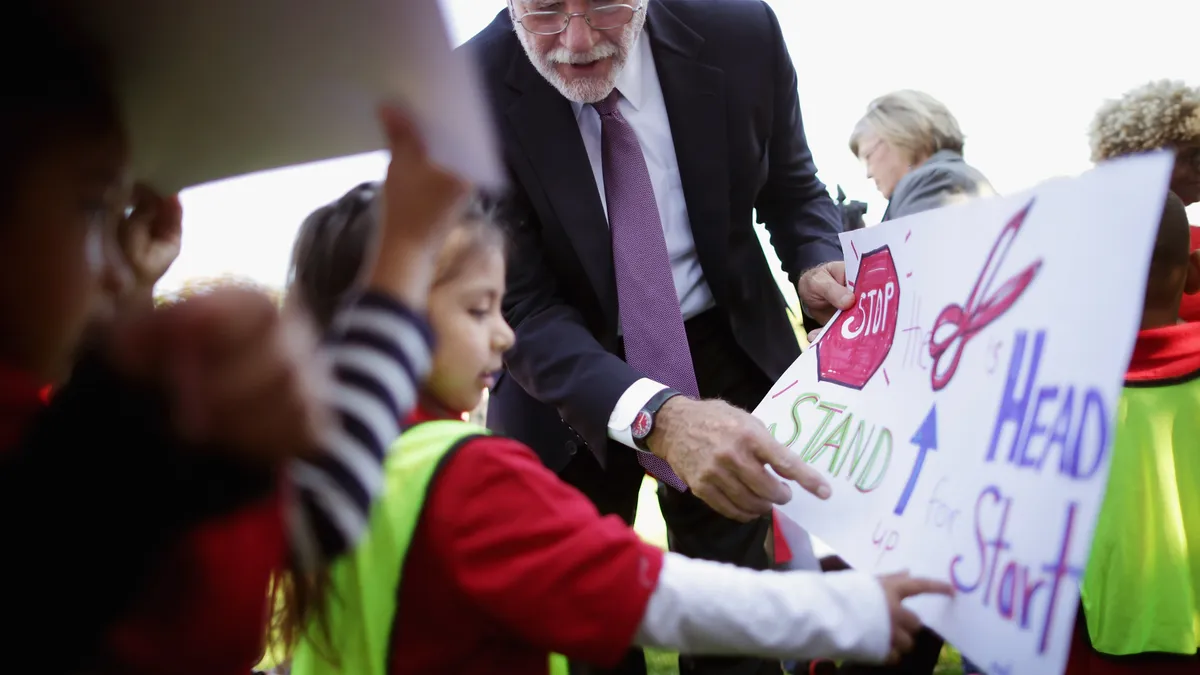

Few have had a front-row seat to the changes in federal education policy over the last 40 years like former U.S. Congressman and current senior education advisor at Cengage George Miller, who was first sworn into the House of Representatives in 1975 and served as the chair of the chamber’s Education and Labor (presently Education and Workforce) Committee from 2007-2011. We recently caught up with Miller, who shared his thoughts on the direction of federal education policy in the U.S.

On changes in focus over the last 20 years

“You can easily ask the question how much has it changed and how much has it not changed. These conversations go ‘round and ‘round. We have designed a system that is for the purpose of extending the educational opportunities as widely as possible within the American society, and that is a complex problem.”

On the responsibility to provide a high-quality education for every child in the U.S.

“This is a path that I believe both our Constitution and the American public have asked policymakers to do: Provide a first-class education to every child and young person and graduate in the country, and that’s played out in different iterations of [education legislation]. First it was trying to get resources to schools that were impacted. Later on, with something like [No Child Left Behind], trying to build on what we know about our successes and trying to get students to perform at the elementary level … and to identify how every one of these populations that are now included in the elementary system, how are they doing?”

“No Child Left Behind forced many districts to confront their students in a manner in which they weren’t doing prior to the implementation of the law. Students were being hidden … students were being discounted for a number of reasons.”

“NCLB required that we identify these populations and that we monitor their progress or their lack of progress in a system. … [It] was tough work for some districts because they weren’t meeting that constitutional obligation to poor and minority students and students with disabilities.”

“[Schools and districts must examine the] allocation of resources. In some cases, you need individual attention, in some cases you need smaller classes or smaller groupings of students. Hopefully, the introduction of technology … allows additional time and an easier path for some students to learn material, [and] allows teachers to act in a different fashion, in terms of how they can help a range of students.”

On the Every Student Succeeds Act

“This is no longer over whether or not the students will be counted or will they have resources, but it’s now back to the question of giving flexibility back to the states and those districts over how to best organize those resources, how to deliver the content in today’s world.”

“There are still concerns on both the right and the left, but as I look at different reports on what states are doing … there’s a lot of really good actions taking place. I don’t know where they’ll end up. I’m always worried that plans aren’t bold enough, but I think these are really good conversations.”

“I think that districts feel they are really included [in the conversation happening at the federal level]. … They can have a better atmosphere to design successful programs for the success of the students.”

“There’s no question that No Child Left Behind was too specific, kind of rigid, and there were a lot of conversations about how you could avoid it. … This is more school-friendly, more district-friendly.”

“This is a new beginning, if you will. We went through the last 10 years under NCLB, and now we have another opportunity, a more flexible opportunity … but we have to get results.”

“[ESSA creates a] more user-friendly process, with accountability, but because it’s more user-friendly and there’s more local design and input, it will bring about more sustainability.”

On accountability

“How do you truly measure whether your school is a quality school or is truly delivering the measure you want, and how do you pick those measures?”

“It’s obviously a moment of transition here from NCLB to ESSA, and all the reports say that states and districts are trying to work their tails off to get this in the right shape, but I think it’s in a pretty healthy atmosphere.”

“It’s tough. They’re dealing with these ever-changing populations. Students enter school and they leave school … but I think this is maybe the best atmosphere that we’ve had in awhile.”

“You don’t want to be like the old Soviet Union, and every five years there’s a new policy, but nothing’s really changing. These schools have got to get better, but we’ve got to help them do that — and help is the big word, you’ve got [to allow for district autonomy].”

“I think the bold plan is … to try to do the very best you can to see that every child succeeds, like the law says. [The challenge is] energizing the districts in a state to really accept that goal. There’s no question that’s what every district wants, they want their schools to do well.”

On the future of elementary education

“I’m optimistic. There’s still some hurdles to go over, in terms of how we measure a successful school and how we [figure out which measures determine success]. … [States will] have good plans for the implementation to comply with the new law.”

“I haven’t been known as an optimist around elementary education [but] I think the process is about right. Can it still be gamed? Sure. There [are] people who can game it and try to get around the system. But watching it from afar, it’s certainly a better atmosphere.”