When it comes to their technology use in classrooms, teachers in the Gwinnett County Public Schools, northeast of Atlanta, probably fall on a bell curve. But according to Tricia Kennedy, executive director of the district’s digital learning initiative, the distribution of how teachers use technology in their classrooms and how frequently has shifted.

Five years ago, teachers on the lower extreme of the curve didn’t use digital technology in their classrooms at all. Now, there are still teachers who use technology less frequently, but Kennedy says there aren’t any who don’t use it at all.

Gwinnett County Public Schools represents a success story when it comes to properly integrating technology into instruction. A number of factors contribute to this, not least of which is the long-term commitment of a stable school board and superintendent. Superintendent J. Alvin Wilbanks has led the district since 1996, and most of the board members have been in office just as long.

Technology coordinators have been in every school since at least 2000, according to Kennedy. These staff members all have teaching backgrounds and work out of the information management department, which means the connection between instructional and IT divisions has been strong for more than a decade.

From there, Gwinnett’s strength has been in strategic planning with instructional practice at the core of its goal-setting and technology as a way to get there. Kennedy has spoken at a number of national forums, where this aim is considered the gold standard.

“Everybody is talking about the need for it to start with instruction and not with the technology itself,” Kennedy said, “but it’s really easy to fall into that trap.”

The Education Week Research Center’s 2016 Technology Counts survey found teachers are most likely to use technology in their classrooms for drills, review or practice exercises. Less common is using technology to create opportunities for collaboration, research or group projects. Studies continue to show that in most classrooms, technology is not transforming instruction.

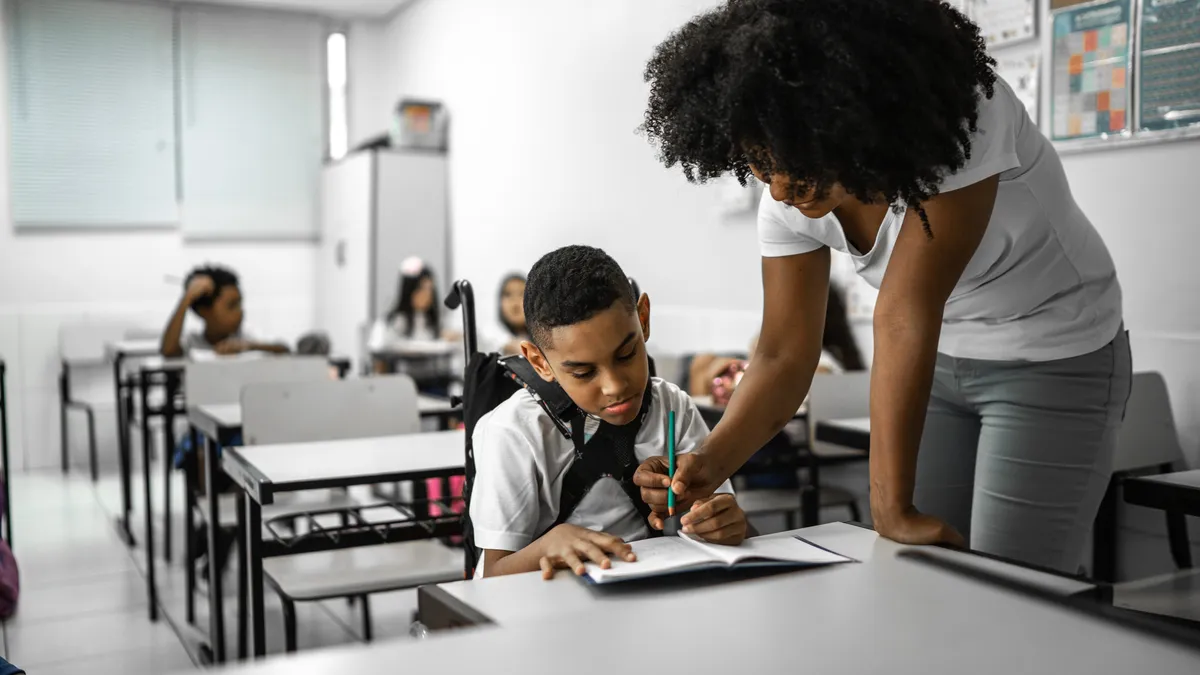

In Gwinnett County, Kennedy says she wants to see the effective use of technology become a standard part of the way teaching and learning happens across the district. Her office has developed a matrix of instructional practices to help teachers think about where they fall in the continuum of effective teaching with technology.

Beginner-level teachers, for example, might share websites with students as a way to give them information, similar to how they might direct students to textbook chapters. At the other end of the spectrum, when teachers reach the transformation stage, they use the technology to enhance learning and give students a chance to take ownership over how they learn new content or skills and how they present that.

The district’s professional development efforts are focused first on making sure instructional practices are solid, research-based and able to reach every student. Teachers don’t get to incorporate more technology into their classrooms until they can prove this.

“Technology can make things efficient,” Kennedy said. “It can make poor instructional practices very efficient, as well, and that’s what we want to avoid.”

The district created a set of strategic priorities in 2010 that would guide its operations through 2020. It quickly became clear technology was going to have to play an important role, and during the 2011-12 academic year, the district launched the eCLASS initiative, which Kennedy leads. eCLASS refers to a digital content, learning, assessment and support system. Gwinnett County Public Schools wanted to figure out what the classroom of the future would look like and, from there, find the right technology tools to help them make it a reality.

Over the course of five years, district leaders defined the initiative, conducted a procurement process, started a small pilot, expanded to a bigger pilot, and then continued with a districtwide rollout. Now the district’s 172,000 students in 132 schools have access to the Brightspace learning management system, which has contributed to a rise in personalized learning.

“It’s not unusual for students to be working on something very different, student to student, from within their eCLASS because it’s easy for teachers,” Kennedy said.

In August of 2015, less than 40% of students were logging into the LMS on a weekly basis. One year later, that number had surged to 70% and it has kept climbing as teachers take advantage of being able to track progress on formative assessments and easily tailor instruction to students’ individual needs.

Kennedy knows some teachers have already reached the transformative stage on the district’s matrix of instructional practices. The key is to keep expanding that population, which Kennedy expects will happen in the years to come.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards