Along the border with Nevada, home visitors in Mono County, California, are parking near the homes of their clients and using hotspots to connect for virtual visits. They’re also recommending activities for moms and young children that only require items typically found in the home.

In Fort Wayne, Indiana, Julie Reese, a Nurse-Family Partnership nurse with Healthier Moms and Babies, is conducting all of her visits virtually and making sure mothers have high-demand items such as wipes, diapers and other supplies. She’s also intervening for those who might have health care needs at a time when physicians and hospitals are overwhelmed.

“They feel like they are having a hard time getting through,” Reese says. “Sometimes they just don’t know the pathway to take to get there.”

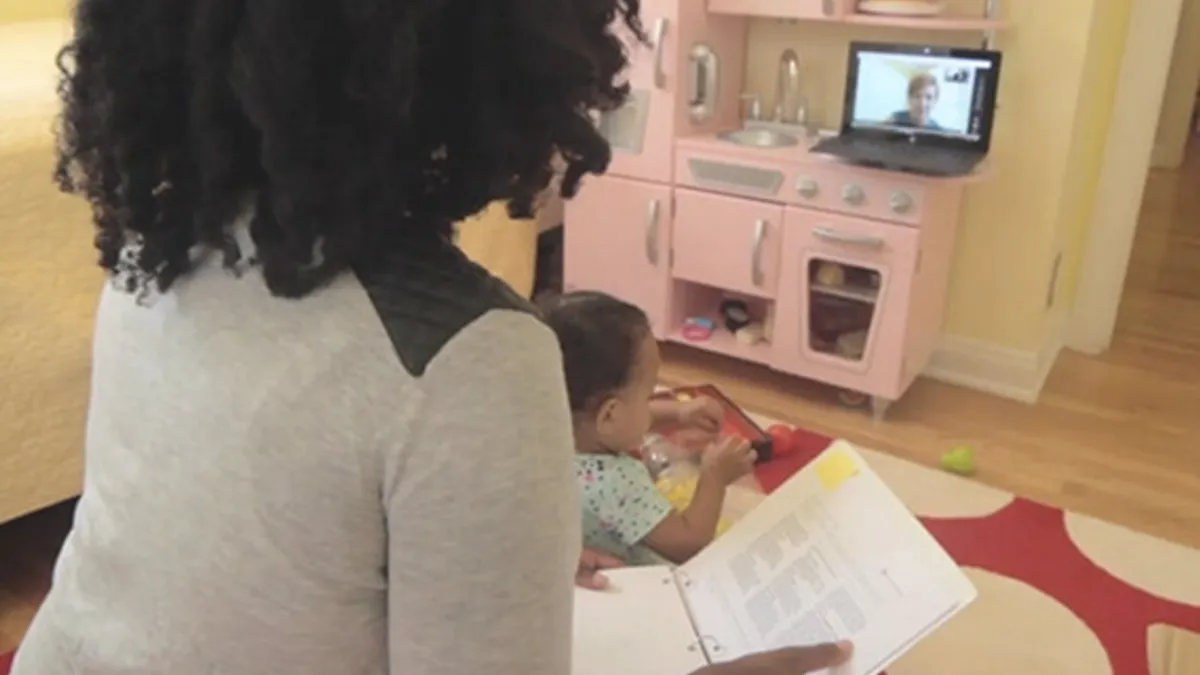

Those are among the ways home visitors are adapting their services during a period in which first-time and at-risk mothers are more isolated than ever.

But the pandemic is also a crisis some in the home-visiting field didn’t know they were preparing for. To better accommodate families, leading national models, such as Parents as Teachers and NFP have been gradually incorporating virtual visits into their practice over the past several years.

“Families have been showing us for a long time that they were ready for this,” says Donna Hunt-O’Brien, vice president of professional and program development for Parents as Teachers, which began in Missouri in 1981 and now operates throughout the U.S. and in six other countries. “I think we’re going to see a major shift toward a new social norm for service delivery.”

In 2015, PAT began working with the University of Southern California’s Telehealth Online Clinic to adapt the program to a virtual format. Through a pilot, leaders have shown “parent educators” can deliver all four components of the model — the visit, group connections, developmental screening and providing resources — remotely. The virtual visits are usually used as part of a hybrid in-person and virtual approach.

But then officials issued stay-at-home orders and “people came flying out of the woodwork” wanting to know more about adapting the model for virtual visits, says Hunt-O’Brien. In a three-week span of time, over 15,000 virtual visits have been conducted nationally and another 12,000 by phone.

Earlier this month, the PAT National Center also became part of the Rapid Response Virtual Home Visiting collaborative — an effort to share strategies for “maintaining meaningful connection with families during this time of increased anxiety and need,” according to the website.

NFP has also been integrating telehealth visits into its model since 2017, and by January of this year, about 85% of local programs were already routinely including virtual visits, “using when needed to meet their clients’ needs, when a home visit wasn’t possible,” says Fran Benton, director of public relations for NFP. That increased to 100% when the pandemic spread throughout the U.S.

‘A preventative approach’

Through the USC pilot, PAT has learned how parent educators — who work with new mothers until their children are ready for kindergarten — can make a virtual visit feel as personal as an in-home one.

First, Hunt-O’Brien says, the visitors need to have “self-awareness of how they are communicating across the screen.” Strong coaching skills are also important, she says, because the home visitors are guiding parents to do what they might have been demonstrating in the home in the past.

Hunt-O’Brien says the virtual visits are lasting as long as they do in person. And a group session went on for 90 minutes.

Placement of the screen can also improve the visit — even putting it at the young child’s eye level so the parent educator can see the home environment from that perspective. Since children are home from school and child care, Colleen Masi, a PAT program manager for the Cope Family Center in Napa, California, suggests home visitors and parents do a home safety check.

Because of the additional stress on families, she is also closely monitoring those she feels might be at a higher risk of child maltreatment. In fact, Dorian Traube, an associate professor and director of the Parents as Teachers @ USC Telehealth program, said because schools and child care programs are closed and a lot of routine doctor’s visits have been put on hold, those who would normally be mandated reporters of child abuse have less contact with families.

“With kids not being in any of these environments, we’re concerned about a spike,” Traube says, adding a virtual home visit is “even more of a preventative approach than it was historically designed to be. We’re able to reach families when nobody else is.”

New mothers, she notes, are also more willing to consider telehealth for mental health issues, such as depression, because they are already used to the format.

Strong relationships first

The families enrolled in home-visiting programs, however, are some of the most vulnerable during this crisis. Reese sees mothers who work as health care aides or in other essential positions. Masi serves several undocumented families who are “not able to access some resources that other families are able to.”

And not all mothers have the devices and internet access that would allow for smooth connections.

“A significant number of our families don’t have devices, or enough devices in homes where older children are doing online school, or Wi-Fi or sufficient data plans,” says Sarah Walzer, CEO of ParentChild+, formerly named the Parent-Child Home Program.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, ParentChild+ was not doing virtual visits. But now — in spite of those challenges — Walzer sees remote visits as “an important and effective way to provide support.”

She says it’s too soon, however, to tell exactly how virtual home visits will fit into the program’s model in the future. “I don’t think we know enough yet about what the outcomes of these visits look like compared to in-person visits,” she says. “And it will be difficult to tell just based on the use during the crisis, because there is so much else going on in families’ lives.”

Home-visitors and program leaders say it’s necessary to have a strong relationship with a family before incorporating a virtual option. Maria Galarza, a kindergarten teacher at Edward Kemble Elementary School in Sacramento — and part of the Parent-Teacher Home Visit network — says she wouldn’t want a virtual visit to be the initial meeting with a family.

“I feel like once you’re in their space, they really value your time and they really value what you have to say,” says Galarza, who has been conducting home visits since 2008.

At this time of year, Galarza, who team teaches a Spanish-English dual language immersion program, would normally be visiting the families of all 48 students in both classrooms.

While she’s teaching her class virtually, scheduling additional virtual sessions with parents isn’t currently part of the plan. But she does say the relationship with families formed at the beginning of year during the visits has improved communication during this time.

“I feel like our team has become stronger because of this” she says, adding parents are also sending the teachers resources they’ve found and want to share with other families.

Now in 24 states and the District of Columbia, the network is providing suggestions for teachers who normally conduct home visits and focusing on ensuring families have access to information about school meals and other local services. Some are also organizing neighborhood drive-throughs so students can see their teachers from a distance.

Even with virtual connections as a more established part of the home-visiting field, the practitioners say they are eager to get back in the homes as soon as they can.

Reese, for example, says she might re-screen children in person just to confirm the parents’ assessments of their children’s growth and development. And families tell Masi they are looking forward to in-person interaction.

“Nobody wants to stay living in this virtual world,” she says.