On a Friday afternoon in Clarkston, GA, students file out of Indian Creek Elementary School and head home to the apartment complex next door where they live.

But instead of spreading out across the large open field at Willow Branch, running to jump on the swing set, or going home alone, they congregate in the leasing office where Allie Reeser greets some with hugs and hands out juice and chips.

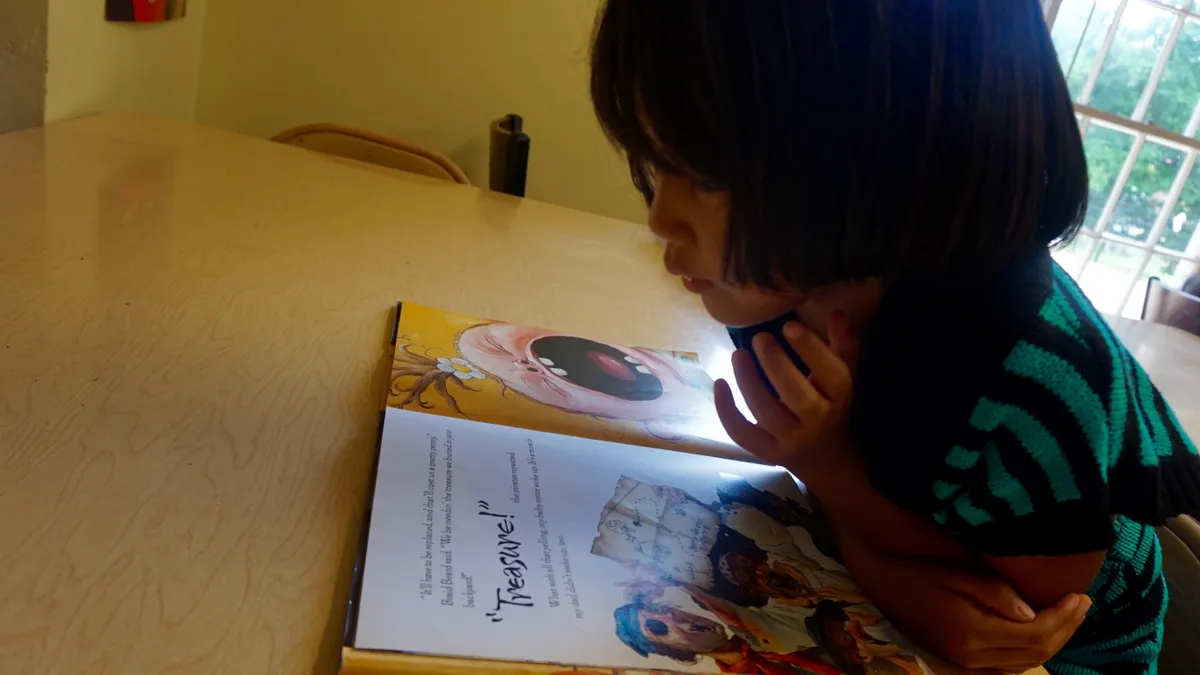

On most days, they’d be pulling out their homework or practicing skills for the Georgia Milestones assessments on a Study Buddy, a mobile device similar to a handheld Nintendo game. But it’s the end of the week, and today they’re settling down to watch “Because of Winn Dixie,” because they’ve been reading the book with Reeser.

This apartment community after-school program, which consistently serves about 80 children in grades K-5, isn’t funded by the local school district or paid for by the parents. It’s an amenity offered as part of their lease, as well as landlord Margaret Stagmeier's effort to bring some stability to this largely immigrant community.

“Just like kids would go to the pool, they go to the after-school program,” Stagmeier says.

This former 6th-grade Monopoly champion, who back then saw real estate in her future, also views the program as a smart business move. Instead of breaking sprinkler heads or leaving trash on the grounds, the young residents are getting help with their schoolwork and practicing for state tests. She spends about $3,000 to run the program, which includes program manager Reeser’s pay and other supplies, but she reaps three times that in savings on maintenance.

Purchasing the complex in 1996, she also pledged to keep rents low at $618 per month, which is less than what many families living in subsidized housing pay. Flourishing vegetable gardens now line the perimeter of the open field, there is a weekly farmer’s market, and as part of a wellness program for residents, she works with nearby Oakhurst Medical to sign families up for primary health care services.

Calling her approach an “education model with a housing solution,” Stagmeier understands the connections between transiency, student achievement and neighborhood safety, but she also knows how most business people think.

“It’s hard to get investors to invest in blight,” she says. “And if you have a blighted apartment community, there’s a 100% chance you have a failing school.”

A 'pathway' to school improvement

Among myriad efforts to “turn around” low-performing schools over the past few decades, addressing students’ living arrangements has not been a prominent strategy. Researchers and social policy experts, however, have long recognized that housing and education are intertwined and that high student mobility negatively affects student — and school — performance. More research is needed, however, on how “housing can be a positive pathway to achieving better school outcomes,” Mary Cunningham and Graham MacDonald of the Urban Institute wrote in a 2012 policy brief.

One challenge, they add, is that many studies compare homeless students to those who aren’t, not accounting for the many other unstable situations in which children live. “Families move in and out of these circumstances, and they may appear stable at one point in time but experience inadequate housing in others,” they write.

An earlier paper from the Center for Housing Policy highlighted the benefits of residential-based after-school programs, such as eliminating the need for special transportation arrangements, alleviating parents’ concerns about whether their children are safe after school and simply being more convenient for parents.

In recent years, officials running public housing agencies and developments have started to see these connections and provide after-school programs, often as part of grant-funded, place-based initiatives, such as Choice Neighborhoods. In Seattle, for example, Catholic Community Services runs its Youth Tutoring Program in Yesler Terrace, a Seattle Housing Authority development.

Another leading example is Eden Housing in California, a nonprofit housing developer and property manager that offers after-school programs in many of its 135 sites across the state, most of which are in the San Francisco Bay area.

When the leaders of Oakland-based Partnership for Children and Youth (PCY) — an advocacy organization that provides technical assistance in the areas of after-school programs, summer learning and community schools — learned about Eden Housing’s educational programs, they were unaware that such programs existed. But that knowledge led to PCY’s HousEd project, which now supports affordable housing providers running education programs through workshops and training opportunities.

Two years ago, PCY also developed Quality Standards for Expanded Learning in Public and Affordable Housing, which are adapted from the widely used Youth Program Quality Assessment. A growing number of “engaged learners” are additionally participating in HousEd’s network, leading to further partnerships.

“We’re grounded in this mission that we want to create education opportunities where kids live,” says HousEd director Jennifer Hicks, adding that school-based after-school programs can rarely offer enough slots to families who want their children to participate. Most apartment complexes, however, have a community center or clubhouse near the pool that sits largely unused during the week. She added that once program staff members became skilled at working with students, they began to connect adults to services as well, and that parents were more likely to be open to support if their children were safe and learning.

“Families are feeling like, ‘If you support my kid, I’m going to listen to you,’” says Hicks.

Attendance Works, the nonprofit organization that has brought widespread attention to the negative effects of chronic absenteeism, is also partnering with HousEd to work with five housing agencies to increase school attendance.

Still, most of these efforts involve the public and nonprofit sectors, which Stagmeier notes does not reflect the vast majority of renters who aren’t eligible for any type of housing assistance but are struggling month to month to pay rent and keep their children from changing schools again.

According to the most recent State of the Nation’s Housing report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, the percentage of families with children living in rental housing has increased, from 32% in 2005 to 39% in 2016, reflecting in part the high rates of foreclosure during the recession.

While construction of multi-family units has increased, the report notes, the supply of apartments renting for less than $800 a month has declined. Close to half of all renters are what the report refers to as “cost-burdened,” meaning that they pay more than 30% of their income on rent. Close to 25 million children live in such families, especially those in families with incomes less than $30,000 per year.

“To make ends meet, these families often do not buy enough food for their households or they substitute cheaper but less nutritious foods, either of which can jeopardize their children’s health and development,” the authors write.

'Parents were so grateful'

Even a slight increase in rent can force such families to look for new housing as Stagmeier found in the first apartment complex where she implemented an after-school program.

That was Madison Hills apartments in Marietta, north of Atlanta. Students living in the complex attended nearby Brumby Elementary School, which, when Stagmeier acquired it in 2006, was on a watch list of failing schools and had a student mobility rate decline of 67%. After the after-school program began, mobility dropped to 41%, all 90 of the children in the program earned passing scores on state tests and the school was recognized as a Title I School of Distinction in 2012.

“We saw gains in our tests scores, grades and behavior with the students that participated in the program,” says Principal Amanda Richie, adding the program manager was another adult who could hold the students accountable for homework and attendance. “Parents were so grateful to have a place for their students to be in the afternoons after school.”

But then Stagmeier’s investors chose to sell the property to a new investment group, which opted to raise the rent and shut down the after-school program. In 2013, the school received a grade of B from the state’s Office of Student Achievement. Every year since then, it has earned a D. Richie says there was a noticeable decline in grades, test scores and good behavior after the program ended.

In addition to Willow Branch, Stagmeier will soon be implementing her model at an apartment complex near a school in Atlanta, and she’s exploring the possibility of operating after-school programs at properties she doesn’t own. She has created a nonprofit organization, Star-C, so the program can receive donations and she can continue to replicate the model. But she has high expectations of any apartment owner who wants to work with her — keep rents low, provide the program director a free apartment, have a facility for the after-school program, and ideally have a school that is willing to be a partner.

Forming housing-school relationships

PCY’s standards for such programs encourage partnerships with schools and a decision-making process that includes school administrators. But establishing such connections with schools can be difficult, and creating data-sharing agreements with after-school providers can take years.

One reason why the program at Madison Hills was successful and students’ scores improved, Stagmeier says, was because she and the program manager were able to work in close partnership with Richie.

The manager worked with teachers at the school to make sure students had the right supplies and resources to do their homework. She picked them up from the bus stop to encourage them to come to the program, and she volunteered at the school.

“It was so great to have a partnership with the neighborhood,” Richie says. “And it certainly felt as if the apartment complex was more of a neighborhood than just another group of apartments.”

Stagmeier and Reeser are still working to develop relationships with leaders and staff members at Indian Creek. Reeser attends the students’ school performances and has sent notes to teachers to introduce herself. She knows it will take time.

Stagmeier is quick to acknowledge that she’s not an education expert, but she does have a perspective on “turnaround” strategies used in many low-performing schools in recent years, such as replacing the staff, state takeovers or private management. The academic gains seen at Brumby Elementary were achieved with the same teachers and the same principal, she says.

Funders, she adds, also don’t fully understand the model. “They say, ‘We gave $5 million to the school.’ They should have put $5 million in the blighted apartment.”

Now at Willow Branch, 80% of the students in the after-school program have earned passing scores on the Milestones tests and students have an average GPA of 3.25. Graduate theology and medical school students from Emory University volunteer as tutors, and undergraduates work at the program as part of a class project. The program also runs during the summer, with even more volunteers, back-to-school medical exams and free school supplies for the children.

Some 6th-graders still attend the program because they don’t want to leave, and looking ahead, Stagmeier would like to add on to the existing building to make room for a middle- and high-school program that would focus on college- and career-readiness. She would also love to acquire the apartment community across the street from Willow Branch, where the rest of Indian Creek’s students live.

Education programs in public housing developments will “never move the needle,” she says. “For-profit landlords have to be part of the solution.”