After an 18-year absence, peanut butter is back on the cafeteria menu in the School District of Lee County in Florida. Difficulty in getting menu items and the rising price of food spurred the reintroduction — with new policies and procedures aimed at protecting children who are allergic.

Food supply chain challenges have limited consistent access to protein products, such as chicken, said Amy Carroll, a registered dietitian and coordinator of student wellness and special projects for the district's Food and Nutrition Services.

Offering peanut butter helps fill that gap for the district, which serves 87,000 meals a day, said Kandace Messenger, director of Lee County Schools Food and Nutrition Services, in an email.

It's not clear why Lee County schools removed peanuts from cafeterias in 2004, but that same year, Congress passed the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act requiring food manufacturers to specifically label food products containing any of eight major food allergens, including peanuts.

Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported food allergies in children under age 18 increased by 18% from 1997 to 2007.

To prepare for the reintroduction of peanut products, Messenger’s team worked with other district departments like health services, academics and custodial to review policies and practices. The district also surveyed members of the Florida School Nutrition Association, a nonprofit that promotes child nutrition programs, and discovered 77% of Florida school districts serve peanut butter in their cafeterias, according to Carroll.

"Basically, involve everyone who can make a difference or have input."

Amy Carroll

Coordinator of student wellness and special projects for Food and Nutrition Services in the School District of Lee County

Previous national School Nutrition Association surveys from 2018 have found peanuts were the No. 1 banned item from schools, but even then, banning peanut food items was not a widespread practice, said Diane Pratt-Heavner, an SNA spokesperson.

Banned food items vary and are often decided at the school level, not by district leaders, Pratt-Heavner said.

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches remain a popular menu item in school cafeterias, according to Pratt-Heavner. When schools serve these sandwiches, they are often prepackaged to avoid cross contamination in the cafeteria kitchen, she said.

Still, Pratt-Heavner is not aware of other districts reintroducing peanut butter to menus, particularly due to supply chain issues, as Lee County has done.

New allergy policy instituted

Before bringing peanut butter back in February, the Lee County School Board approved a policy for allergy management that allows individual schools to limit foods that students or others may bring into schools for sharing.

The policy also requires school staff to follow procedures for student accommodations under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Section 504.

Although the district has operated peanut-free kitchens since 2004, students have been allowed to bring peanut items to schools, Carroll said.

The new approach for allergy management made sense because — while other food allergens like milk and tree nuts continued to be served — peanut butter was the only food product banned in the district's cafeterias, she said.

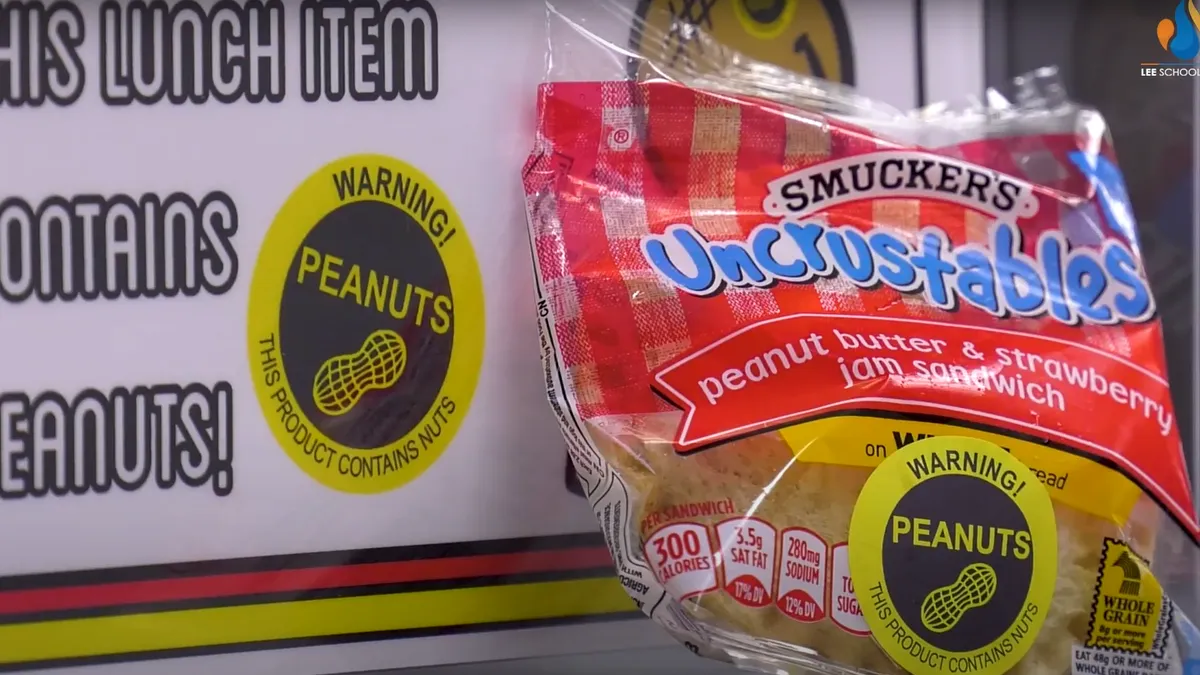

The district created several procedures to minimize allergic reactions to peanut butter. For instance, cafeterias have signs warning some food items may contain peanuts, and food items that contain peanuts are marked with stickers.

In addition, the district updated its list of students with peanut allergies after urging parents to notify the school system of allergies if they hadn't done so already. That information is entered into the point-of-sale system so if a student with a peanut allergy checks out with any peanut items, the system will alert cafeteria workers to remove the item from the student's lunch tray.

Food and Nutrition staff at all Lee County schools were trained on the new policy and protocols in the cafeteria. Likewise, school custodians were trained on cleaning methods to mitigate the spread of food allergens, a district video explained.

Carroll said the district is starting small by offering only one item containing peanut butter in cafeterias: individually wrapped Uncrustables peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

According to the district's website, 1,325 of its 97,360 students have peanut allergies.

Nationwide, about one in 13 children — roughly two per classroom — have a food allergy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported.

Among children, hospitalizations for food allergies tripled between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, according to Food Allergy Research and Education. Moreover, the group found that over 40% of children with food allergies have experienced a severe allergic reaction such as anaphylaxis.

Supply chain woes bring last-minute allergy alerts

Pratt-Heavner pointed to concern about managing all kinds of food allergies as districts continue to face supply chain-induced shortages of various food items. When there’s a last-minute substitute on a menu, school nutrition managers have to review the ingredients and notify anyone who might be affected, she said.

“It’s one of the reasons that school meal programs have been so stressed during this period, because they’re having to do a lot of that really critical last-minute work to make sure any menu change isn’t negatively impacting their student body,” Pratt-Heavner said.

As more children are diagnosed with food allergies, Dave Bloom, CEO of food allergy resource site SnackSafely.com, said he is worried about schools considering a loosening of food allergy policies and easing certain food bans.

“It’s very concerning, but on the other hand, we completely understand that the supply chain is fragmented,” Bloom said.

It’s still important that schools communicate to all parents, even those without children who have food allergies, how severe and life-threatening a food allergy can be, he said.

As supply chain shortages continue, it’s possible other districts could follow in Lee County’s footsteps, said Kristi Grim, senior director of national programs at Food Allergy Research & Education.

For districts looking to pivot on food allergy policies, FARE recommends cleaning tables that students eat on frequently. It’s important students are washing their hands and that younger students in particular are monitored so they don’t share foods they could be allergic to, Grim said.

Parents should also be consulted as to whether they want their children to sit at separate tables based on food allergies, Grim said. Sometimes this strategy makes parents feel safer, but at the same time it can make students feel isolated, she said.

The CDC recommends these steps for schools managing food allergies:

- Ensure the daily management of food allergies for individual students.

- Provide professional development for staff members about food allergies.

- Prepare for food allergy emergencies.

- Educate children and families about food allergies.

- Create and maintain healthy and safe educational environments.

Communicate policy change

Overall, schools and districts need to be transparent about these policies, Grim said. When it comes to communicating food allergies, schools should not avoid or hide from the topic, she said, as doing so could cause parents to lose trust in the school.

To communicate the policy change in Lee County, the district hosted a Facebook Live event, created a YouTube video, developed two podcasts and published a 14-page digital magazine about why and how the district made the change.

Lee County's Messenger and Carroll advise school systems considering similar adjustments to plan for the change in advance and talk with stakeholders to be sure policies and procedures are clear. And it takes time: Lee County officials started their work on the change in October, four months before implementation.

"Basically, involve everyone who can make a difference or have input," Carroll said.

Not every district is successful in attempting to put peanut butter on menus. Florida's Leon County Public Schools reversed course in 2020 when considering introducing peanut butter sandwiches due to pushback from concerned parents, according to Foodservice Director.

During her research, Carroll contacted the National Peanut Board with questions and guidance about anticipated resistance. Although some people voiced concerns about the change before it was implemented, Carroll hasn't heard any negative comments since the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches hit the menu.

"The whole process went well," Carroll said. "Had there not been supply chain problems, we might not have done this."