Occupying just one square mile, Rhode Island’s Central Falls School District is located in the smallest town in the nation’s smallest state. But despite its small size, its equity concerns loom large.

The six-school district, which has been under state takeover since 1992 because of financial hardship, enrolls 2,878 students, 68% of whom are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Of the total population, 80% are students of color, with a majority — 54.3% — being Hispanic/Latino. Additionally, 24% are English language learners.

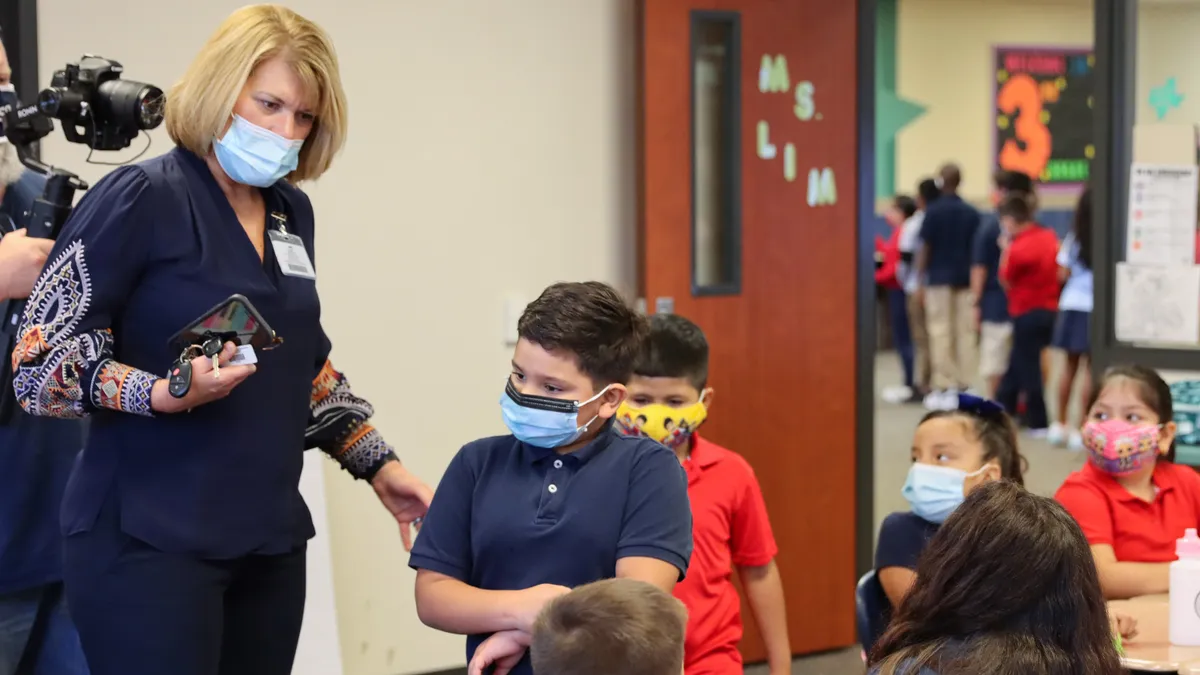

Among the equity challenges identified in the past is the fact that most of the district’s teachers don’t come from similar backgrounds to their students or have direct understanding of their experiences. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded this by further limiting opportunities available to learners.

Inspired by the rise of learning pods in more affluent communities, however, district leaders partnered with the local Highlander Institute and Freedom Dreams to adapt their own approach to the model.

During an afternoon session at last week’s SXSW EDU conference in Austin, Texas, panelists discussed the district’s community-led learning hubs, how it gained community and teacher buy-in, and what this could mean for reimagining and diversifying the school system’s teacher pipeline.

Engaging the community

Central Falls’ goal was to create a community-led learning pod model to re-engage students “lost” during the COVID-19 crisis while also diversifying the district’s educator pipeline. A pilot launched in spring 2021 has since scaled up to serve 80 students.

In designing its approach to the learning hubs, Central Falls wanted to engage community members as pod leaders to build bridges between the students’ interests and learning, said Tatiana Baena, the district’s director of grants and federal programs.

With a focus on three core values of empowerment, equity and excellence, the district identified ideal traits for pod leaders, including:

-

They must be someone with a connection to Central Falls: They live there, went to school there, work there or have family there, for instance.

-

They must have cultural competence, commitment, accountability and willingness to go the extra mile to connect with students and families outside traditional school hours and structures.

-

They must be willing to not only help students in developing academic skills, but also willing to learn and seek help if they need to expand on any of their own skills in doing so.

-

They must be able to help students identify their passions and interests.

-

They must be able to work with students up to 18 hours a week on a flexible schedule, meeting either individually or in groups.

In a one-on-one setting, the pods might include individualized mentoring around academic skills, goal setting or other needs. With groups, the focus might shift to helping learners form relationships with one another, supporting the students’ social-emotional needs by building a sense of community that was lacking during the pandemic.

In-person group time might also include activities that further those goals, including trips to visit the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, playing basketball or celebrating birthdays.

In her work with Central Falls on the community learning hubs, Simona Simpson-Thomas, founder and CEO of Freedom Dreams, said some initial tension around the idea came from community members. Freedom Dreams is an organization focused on building innovative and sustainable systems to empower students of color.

“They also have shared their own trauma, in some cases — experiences with the same high school that they're now trying to come back and give [at],” said Simpson-Thomas. But in trying to understand how they could support an environment that they didn't necessarily feel was supportive for them, many realized they could do something to create a better situation for current students.

While social experiences within the pods have varied, Simpson-Thomas noted one result so far is students feeling more comfortable by seeing others in the pods who look like them, or when they find that their pod leaders went to school with their parents.

The district has also tracked student attendance and engagement data in the program, finding growth across all pods, the panelists said.

Gaining buy-in

When planning the community learning hubs, the district initially held focus groups with students and families, said Malika Ali, chief innovation officer at the Highlander Institute, a school improvement nonprofit that also partnered with Central Falls.

“A huge part of what we heard from the families in terms of what they wanted us to prioritize was around that social aspect, the social-emotional piece, the psychological impact of the pandemic on their kids,” Ali said.

Teacher focus groups, however, were a little more difficult, Baena said.

Asking educators to buy into a “bold, new vision” can be a tough prospect on its own. But on top of the 1992 state takeover of the district, a 2010 adoption of a turnaround model under a previous superintendent saw a significant number of teachers and administrators fired, with just 50% hired back.

This created some scarring among educators, Baena said, with educators asking, “What role do I play then if pod leaders are going to be doing all of this?”

In the teacher focus groups, which Freedom Dreams helped facilitate, Baena said the district was ultimately able to fully explain the model and how it differed from the day-to-day school experience. Teachers were encouraged to view pod leaders as partners rather than competition.

The district has also assembled a family and community engagement team to oversee the project, in addition to getting school counselors onboard.

The counselors have been able to serve as an additional bridge to build relationships between pod leaders and educators, allowing both parties to share the experiences students are having or get more information on academics.

“It was a little difficult at first, but I think we're finally getting to a place where people are seeing results,” Baena said.

“I think most of the time when you're doing any kind of system-level change, it's just a matter of people not knowing their roles and responsibility,” Simpson-Thomas added.

‘Training up’ to diversity pipelines

While initial funding from grants through the Center for Reinventing Public Education and The New Teacher Project “allowed us to kind of kick this off,” Baena said, finances become a question for long-term planning.

The district is currently exploring ESSER funding, Title I and Title IV grants, and other grant opportunities to continue the work.

Ideally, Baena said, they would love to have every 9th-grader paired with a pod leader who can follow them on their journey to 12th grade. The district would also like to build capacity to “train up” pod leaders and thereby diversify its educator pipelines.

“Just like we're tracking the academic mindset development of our students, we're also tracking that for our pod leaders in addition to how they're seeing their own confidence in supporting 9th-graders, their knowledge about what it takes to be an educator, and then their interest in that, as well,” Ali said. “We have a few pod leaders who, after becoming pod leaders, have taken on other roles in the district and actually in the school.”

Baena added that it also requires commitment on the district’s part to recognize pod leaders’ potential. “It doesn't have to be a certified role. It could be as a support role or a homeschool liaison or a TA,” Baena said.

Among applicants in its hiring pipeline for the third round of pod leaders, the district is also seeing non-teaching staff members who may have previously never considered roles in front of students.

“They're seeing the success of the program, and now they're being interested in serving as a pod leader,” Baena said.