Enter a cognitive psychology class at John Overton High School in Nashville, TN, and you’ll find students connecting lessons to their understanding of cultural diversity. Down the hall, science students are assessing the state of climate change and biodiversity preservation in the Great Barrier Reef, and history pupils are applying political contexts abroad to the makeup of American ideals.

These types of themes aren’t part of the average high school curriculum.

When it comes to preparing students for college and beyond, education advocates often say the emphasis at the K-12 level centers too heavily around teaching students how to correctly answer questions on tests, rather than developing critical thinking skills. Recognizing this, John Overton and other schools around the U.S. are employing the Cambridge Assessment International Education standards — but many colleges are behind in recognizing them.

Here, we flesh out why college and K-12 administrators ought to know about them.

Cambridge Assessment: What’s it all about?

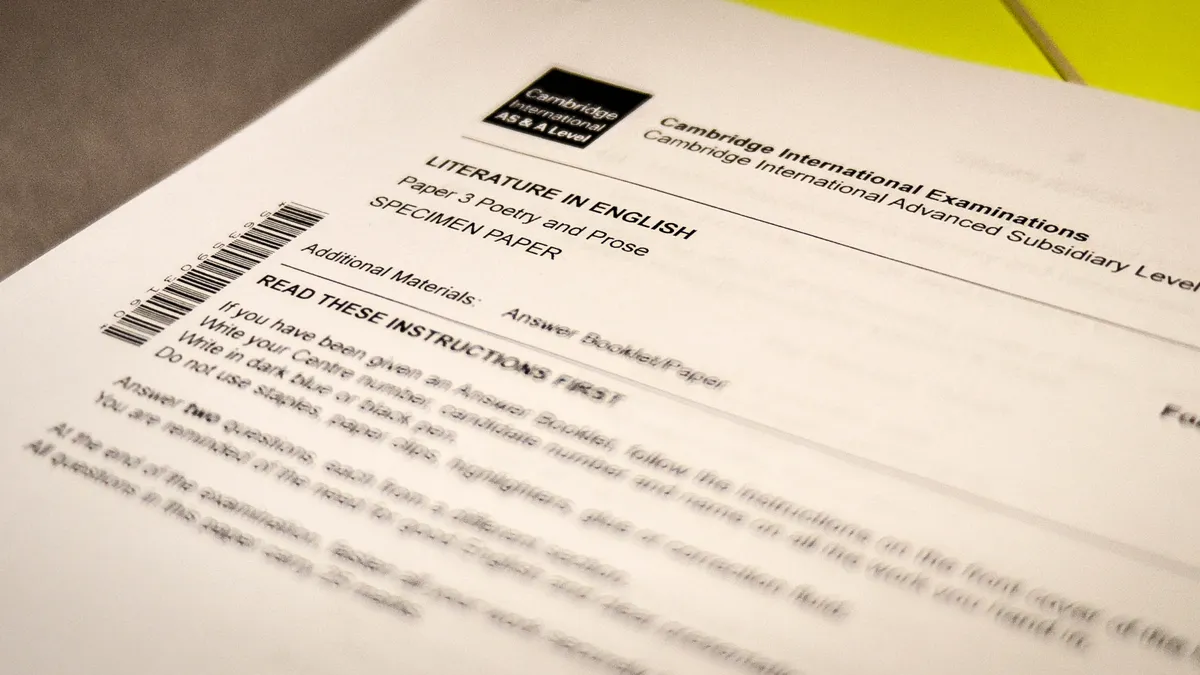

Cambridge Assessment International Education’s International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) curriculum is a rigorous set of academic standards recognized by high-ranking colleges and universities around the world in nations ranging from Denmark and Germany to Egypt and Kenya. The curriculum is meant to give students a globally recognized academic background and a taste of post-graduate thinking before they leave high school.

Jill Pittman, John Overton's principal, said through implementation of Cambridge standards about five years ago, she’s seen a tangible difference in the way her students think.

“Kids only learning how to memorize content has always been a frustration with state standards,” said Pittman. “The kids may know a ton of things, but if they haven’t thought about it and synthesized their knowledge, there is no way they are going to get to higher levels of those rubrics. Part of why I love the [Cambridge] curriculum is because it helps kids get to those levels.”

The standards are geared toward teaching students how to think, said Tristan Stobie, director of education for Cambridge Assessment, which has existed for more than 150 years based out of Cambridge University in England. “The construct of validity is central to our model; it’s not enough to just know content," said Stobie. "You have to be able to apply your knowledge, which incorporates higher-order thinking skills.”

Cambridge assessments center on assessing student understanding, so learners have to demonstrate mastery around particular concepts, and they require skilled examiners. "Long answers to critical essays is just one form of assessment that demonstrates that kind of thinking," said Stobie. "We don’t separate assessment from understanding.”

With Cambridge standards serving more than a million learners from 10,000 schools in 160 countries, more K-12 U.S. schools are finding the curriculum appealing. For example, the Corinth School District in north Mississippi, which was given the distinction "District of Innovation" by the state after it adopted Cambridge standards. District Superintendent Lee Childress is quoted in The Hechinger Report as saying the change has helped the district close achievement gaps between students.

Cambridge reports over 300 schools in the U.S. now use the standards. But even with greater popularity, Cambridge adoption still pales in comparison to Advanced Placement test use and International Baccalaureate adoption, with the College Board reporting 4.7 million AP exams administered to U.S. schools in 2016 and IB reporting over 1,800 schools using its curriculum this year.

Putting the “college readiness” debate in context

Like Pittman, other education stakeholders have questioned just how college- and career-ready Common Core state standards are for students. A 2015 survey of employers and admissions officers by Achieve Inc., one of the organizations responsible for writing the Common Core state standards, found the overall perception of high school graduate readiness has declined since 2004.

Specifically, the study indicates that of the 767 college instructors from four-year and two-year colleges, universities and technical institutions surveyed, 78% believe public high schools are not doing a good job preparing people for higher education. That statistic was 65% in a 2004 survey. And, of the 407 employers questioned, 62% said U.S. public high schools were not doing a good job of preparing students for the workplace. That number was at 38% in 2004.

Meanwhile, employers cited most valuable skills as being non-academic ones: acting honestly, treating others sincerely and genuinely, sustaining effort and keeping an open mind. The discrepancy in expectations versus reality lies at the heart of the K-12 curriculum debate, as well as what Stobie said Cambridge is considering throughout the construction of its standards.

“Universities want students who are prepared for university who are critical independent thinkers, employers want students who have so called 21st-century skills including problem-solving skills,” he said. “We try to make sure the nature of our curriculum and the pedagogy that supports it nurtures those attributes in students and prepares them for the world of work, as well as gets them into university.”

The business case for colleges

“When I see a youngster has done Cambridge International, that tells me they have really been taught a critical way of thinking,” he said. “You might have students who come from a low-income background and they have taken their ACT and maybe didn’t score as well, but if that student is thriving despite the barriers within these standards, than it puts them in a positive light for the admissions officers.”

In the U.S., more than 500 institutions — MIT, Penn State University and all Ivy League schools, among others — transfer Cambridge curriculum courses into college credit. But, with more than 4,700 degree-granting institutions in the nation, a significant number don't recognize Cambridge standards.

So, while administrators like Pittman have seen tangible results, she said it's difficult ot explain to institutions what the standards mean and how they ought to translate into college credit.

“It has been a little bit frustrating for a lot of our kids because Cambridge is new to this area," said Doug Trotter, Cambridge coordinator and teacher at John Overton. "We’ve had kids apply and say 'Hey we’ve got this credit,' and schools come back and say 'What is that?' " He noted he’s tried to rectify the situation, often speak with admissions officers on what the standards mean for student experience.

Philip Ballinger, associate vice provost for enrollment management at the University of Washington, said the larger issue is simply that U.S. institutions have been slow to recognize the standards. Like Christiansen, he is also one of several admissions officers that have served on the U.S. Higher Education Advisory Council meeting with Cambridge International to better spread the word to institutions and help them learn how to transfer credit.

"A lot of universities that have international students have been aware of Cambridge curriculum and assessments for a long time because many international students were educated using that curriculum and taking those assessments,” said Ballinger. “But that hasn’t been true historically in the United States. In the past decade plus there’s been a slow introduction and adoption in Cambridge standards.”

“If they don’t recognize the program or the quality of the program then they are perhaps missing out on some valuable additions to their campuses," he continued. "I think there is definitely a business case here."

“When we see a Cambridge student, they’ve really been set up in a very powerful way to be successful at universities here, as well as in the U.K., New Zealand and around the world,” Christiansen added.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards