Less than a week into her new job as superintendent of El Rancho Unified School District in Pico Rivera, California, Frances Esparza is already working on ways to boost parent engagement.

Near the top of her to-do list was reviewing the district’s policies for parent volunteers — and whether families were footing the bill for routine background checks before they could step foot on campus.

“We want more parent involvement,” she said. “Parents shouldn’t have to pay for that.”

And at least in El Rancho, they don’t, much to Esparza’s relief. But it’s an issue districts across the country are grappling with — removing barriers for outside participation on campus in ways that don’t compromise student safety.

In the Los Angeles Unified School District, that meant recently reevaluating the “fiscal and bureaucratic hurdles” for families, said Antonio Plascencia, director of civic engagement in Superintendent Austin Beutner's office. In January, the district started covering the $56 fee for parents to get fingerprinted as part of the volunteer vetting process. The district also changed to a tiered system, leaving the most stringent checks for parents who will have the most one-on-one contact with students.

“The superintendent was meeting with families across the district, and one of the highlights that came about was how fees for family engagement were an obstacle,” Plascencia said.

It’s common for districts across the country to require background checks for parent volunteers — from one-time field trip chaperones to room parents. In schools that use Raptor Technologies, a popular software provider in this space, these checks can range from $5 to $25, according to a spokesperson for the company.

Fingerprinting is typically an additional cost charged by the U.S. Department of Justice. Some districts also require a health screening for tuberculosis, which may be covered by health insurance but not by the school system.

Sandy Mendoza, director of advocacy for the Los Angeles-based nonprofit Families in Schools, said LAUSD’s requirements themselves aren’t a tough sell. Above all, parents want their children to be safe from violence and people with bad intentions. But the fees were keeping some low-income parents from even trying to be involved in their children’s schools, limiting the diversity of parent perspectives.

“You do what you can” to prevent bad things from happening, Mendoza said. But “maybe not at the expense of parents who just want to do right by their kids.”

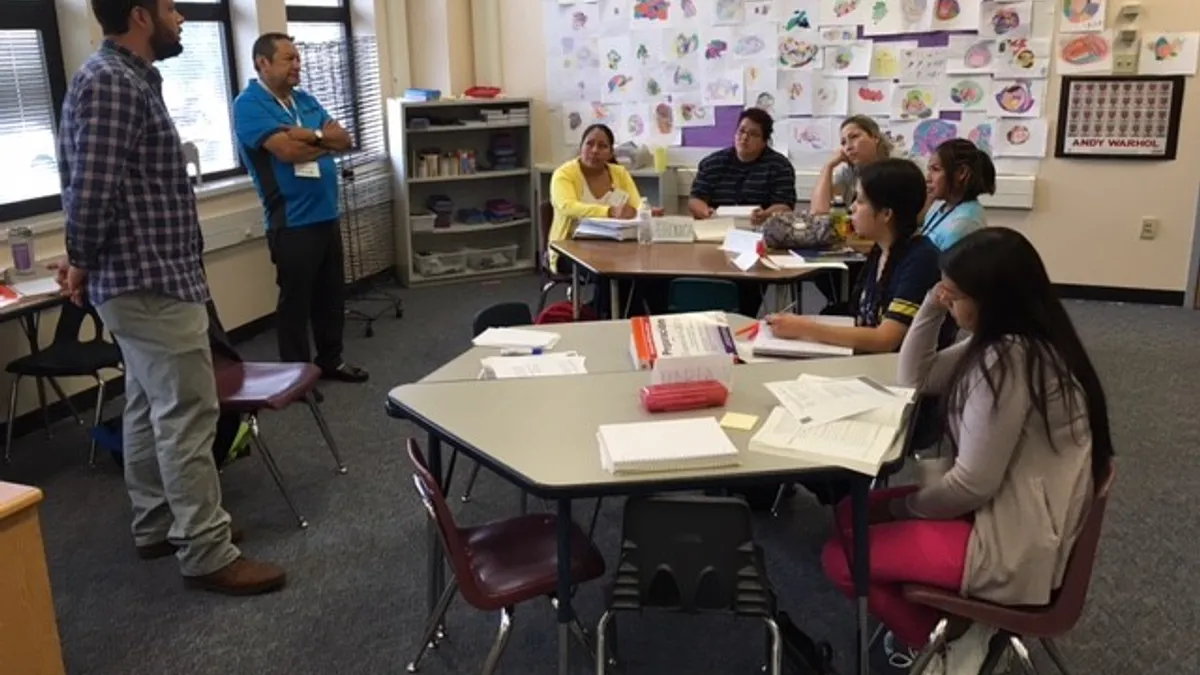

'Parents as partners'

Balancing parent engagement with student safety is a topic retired superintendent Joseph Erardi often discusses with school leaders in his role as a safety consultant for AASA, The School Superintendents Association.

Though there are schools that close their doors to parents and other volunteers in the name of student safety, he doesn’t recommend that approach.

“I am a huge proponent of parents as partners,” he said.

Erardi most recently oversaw Newtown Public Schools in Connecticut during the aftermath of the infamous Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. There, parents who passed their background checks were also required to undergo a brief safety training session to learn what was expected of them in case of an emergency.

“I think it’s an integral part of school safety,” Erardi said of having parents involved. “It’s a really important piece to the plan.”

That’s been the case in Esparza’s experience, too. During previous stints working in LAUSD and the Boston Public Schools, she noticed safety improved when parents were around. This was especially true in one alternative school, where the student body included opposing gang members and ex-cons, she said.

“When kids knew that their neighbor or their friend’s mom was on campus, they weren’t going to do something dumb,” Esparza said. “It really helped us build confidence in the school around security because (parents) were able to be there as supports.”

But districts don’t always do a good job of communicating with families, she said.

Throughout her career, she’s met some parents who have thought they had to be legal residents or even U.S. citizens to volunteer, when immigration status isn’t something a typical volunteer background check detects. Others have gotten radio silence from central office after submitting their volunteer paperwork, unsure of whether they were denied or had yet to be processed.

Now as a superintendent, Esparza wants to make sure that doesn’t happen in El Rancho. Her eventual goal is to build parent community centers at every school, where parents can come together to plan activities and have more active roles on their children’s campuses.

Whatever the approach to parent engagement and school safety, superintendents must talk to their communities before making any decisions, Erardi said.

“You step back and you listen to the voices,” he said. Districts that “are genuinely wanting parents as partners — those are the districts that have the best safety plans.”