Before March 2020, inequitable school discipline practices were a major concern for advocates and educators alike.

"There was a real discipline crisis" for students with disabilities and students of color, said Wendy Tucker, senior director of policy for the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools and a former member of the Tennessee State Board of Education.

Most recent numbers from the U.S. Department of Education's Civil Rights Data Collection show while students with disabilities served under IDEA make up 13% of the total enrolled student population in the country, they represented the majority of students who were physically restrained and secluded in 2017-18. And while K-12 schools overall have decreased use of out-of-school suspensions, Black learners and students with disabilities remained twice as likely as their peers to be suspended, according to Child Trends' analysis of federal data from 2011-2016.

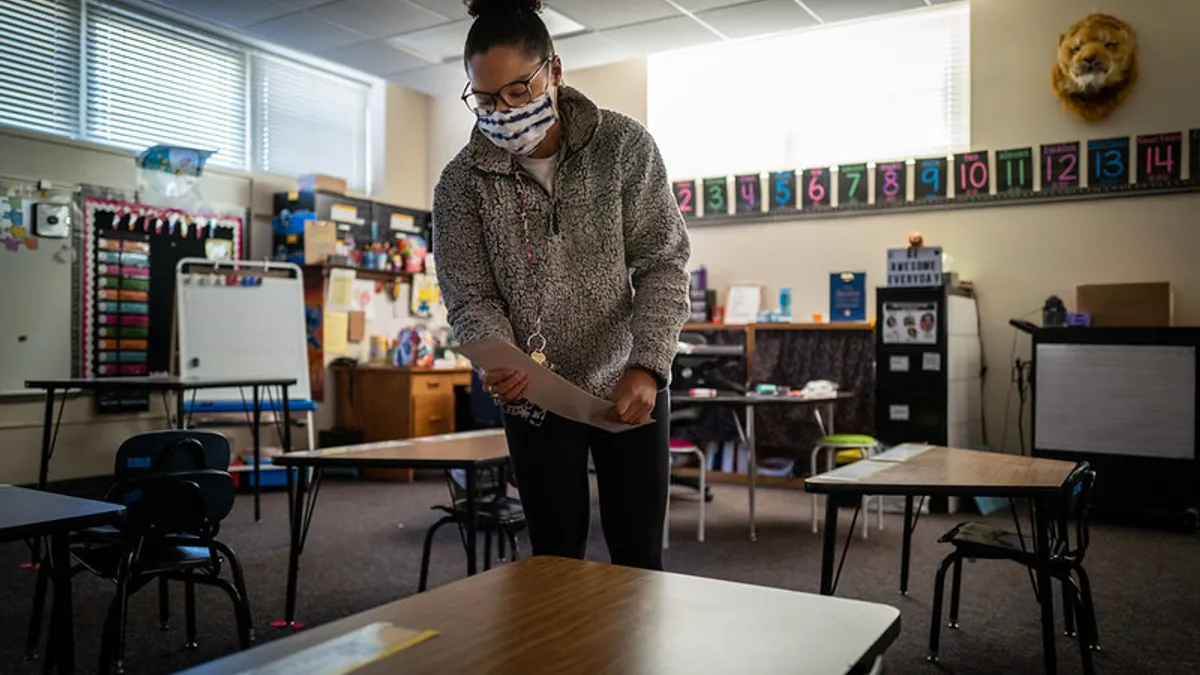

But like many other areas of education, long-standing school discipline practices were impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. Here are some ways they have stayed the same and are changing.

Online discipline hard to implement

Remote settings have made traditional disciplinary measures more challenging.

"When you're in-person, you have access to more coercion tools," consultant Mike Paget said, adding he doesn't necessarily support such methods. "For example, [take] proximity influence, where a teacher walks up into the area of students who are not as engaged as they need to be. That can be both effective and it can be intimidating." Paget's work involves helping schools with students' emotional and behavioral challenges.

There are also more punitive measures being taken despite current remote or hybrid learning models.

"We’re hearing a lot of disturbing things," Tucker said, referring to an incident in October when a 9-year-old Louisiana student was almost expelled after a teacher reported seeing a gun in the child's bedroom. "But we’re also hearing things about kids, when they act up on a Zoom, being put into a Zoom breakout room as sort of an in-school suspension."

Teachers, Tucker said, are also muting microphones or turning off students' cameras. "While that makes sense when you see a teacher struggling with 26 students on video, it’s an easier solution," she said. "It’s a removal of that child from the educational environment and the data needs to be collected.”

Not everyone supports utilizing these types of punitive approaches with the tools at hand, however.

"I don't think that the technology should be used to create an alternative learning environment because of a suspension or expulsion. I believe that there has to be some equity in the implementation of [technology]," said John Jackson, president and CEO of the Schott Foundation for Public Education, which raises funds for racial and educational justice movements. Jackson also was the senior policy advisor in the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education under the Clinton administration. He said he worries that using technology to create an alternative, remote learning environment could promote punitive discipline.

Andy Jacks, principal of Ashland Elementary School in Manassas, Virginia, said he is trying to remind educators to "look at the big picture." "You can’t overreact in these situations when you’re in their home [virtually]," Jacks said.

Schools 'doubling down' on relationships

Many educators and others say the pandemic — and the resulting social isolation, stress and other negative implications on mental health — has led to an uptick in social-emotional awareness. Schools across the nation made a concerted effort to leverage their time and resources to check in with students, ensuring their physical and mental health needs were met.

With remote learning in play, there should be a decrease in the number of students being suspended or expelled, said Jackson. "I think it would be more difficult to punish a student virtually," he said.

Instead, schools are "doubling down" on relationships, said Jordan Posamentier, director of policy and advocacy at Committee for Children, a nonprofit that designs SEL programs. “With a different setting, there's a lot of opportunity here — to the point where I think some school districts realize they can press the 'reset' button in a way that would’ve been harder had they kept going in school and tried to shift gears in the same settings under the same conditions,” he added.

Multi-tiered systems of supports, which were gaining traction as an alternative solution to punitive discipline prior to the pandemic, have become even more important, Posamentier said.

Paget echoed that a remote environment requires "an even greater emphasis" on relationship-building, "where [students] actually miss you if you don't check in with them," he said.

Likewise, the pandemic has improved relationships between many teachers and parents, in some cases, as a result of their increased collaboration, Tucker said.

More ideas for keeping kids in classrooms

An American Civil Liberties Union analysis of federal data from the 2015-16 school year showed students collectively lost close to 11 million school days that year — or roughly 66 million hours of instruction — as a result of out-of-school suspensions, with Black students and children with disabilities disproportionally impacted when compared to their peers.

With steep learning losses predicted as a result of the pandemic, education leaders stress the importance of having as much time for instruction as possible, now and when they return full-time to buildings.

"Say a kid is [in school] two days a week; you can’t suspend them for a day," Jacks said. "That’s pretty staggering."

He expressed the need to reform many longstanding practices in education, including discipline and class sizes, which he said are inextricably linked.

Jacks also said he has noticed that reducing class sizes in the wake of COVID-19 has made school discipline "tremendously easier." "In fact, I’m seeing that we could solve a huge amount of our disciplinary issues if we could just reduce class size," he added.

Likewise, the principal said schools can be be more lenient on minor school policies like dress codes, adding it's about picking and choosing to discipline behaviors "that really interfere with learning."

Tucker, a former lawyer, said health concerns and requirements like mask-wearing, combined with increased behavioral challenges as a result of heightened trauma and anxiety, could lead to more suspensions and other disciplinary actions for students now in-person full time or in hybrid models.

"You think about the kid with the mask who has a hard time wearing it, and in school you have a 60-year-old educator who is diabetic and is in the high-risk category," Tucker said. "You can’t really blame them if they don’t want to be around a screaming kid without a mask.”

To help avoid such situations, Tucker said educators should reach out to families before in-person learning resumes to identify and mitigate potential challenges. "So by the time they come into the building, you have collaborated with the family to set you up for success," she said.

Ongoing challenges remain

In New York's Buffalo Public Schools, where leadership is in the midst of adopting new disciplinary policies including restorative justice practices, the local teachers union released a survey highlighting its concerns. In their responses, teachers claim physical altercations, verbal profanities and threats to safety, among other incidents, were met with limited to no disciplinary action. Buffalo Teachers Federation President Philip Rumore said that kind of response to misbehavior "sends the message to the other students that the behavior is acceptable."

"It’s not the panacea," Rumore said of restorative justice. "However, it can work if it is done with fidelity — if there is proper training with teachers, if there is support of the principal, and if there is time to do it." He also said a lack of school psychologists and counselors poses hurdles to successful implementation.

Tonja Williams, the district's associate superintendent of student support services, told local news outlet WKBW the program "will work," but "it will just take some time for everyone to be implementing it with fidelity."

Education leaders have said a systemwide shift away from punitive discipline and toward restorative justice and other practices takes time and resources — luxuries many districts are short on.

"You're not going to expect a night-and-day turnaround," Posamentier said, "but every little bit is something that a school can do." Even one SEL lesson a day could help educators and students work on self-regulation and build coping skills, he added.

SEL experts and educators have also said the need to start early and with community support — if there’s a troubled student, quite often there are troubled families.

"I think sometimes schools want to take on all of it at once and it becomes overwhelming," Posamentier added. "You don't have to do that. It's one lesson at a time, one relationship at a time, and that accumulates where I think there's a lot to be done without boiling the ocean."