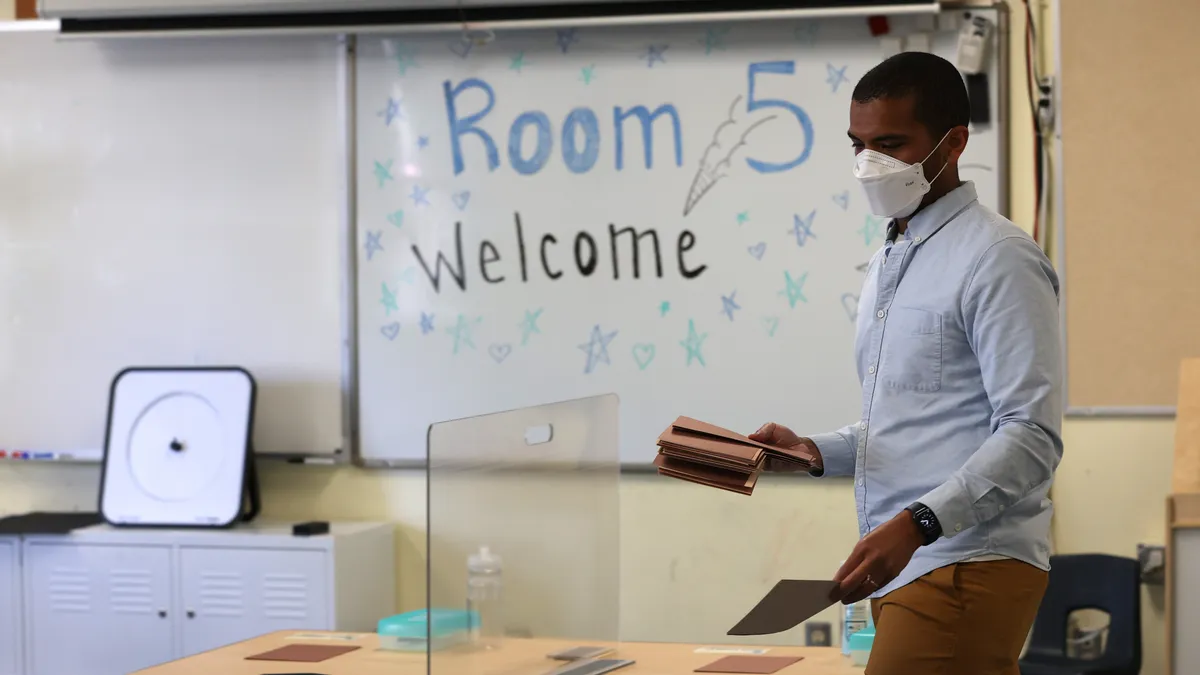

Superintendent Baron R. Davis spearheaded the Premier 100 program, which recruits, retains, and elevates men of color in the Richland School District Two in South Carolina. Before coming to Richland Two in 2012—and becoming the district’s first Black superintendent in 2017—Davis served as a school leader in rural, urban and suburban systems.

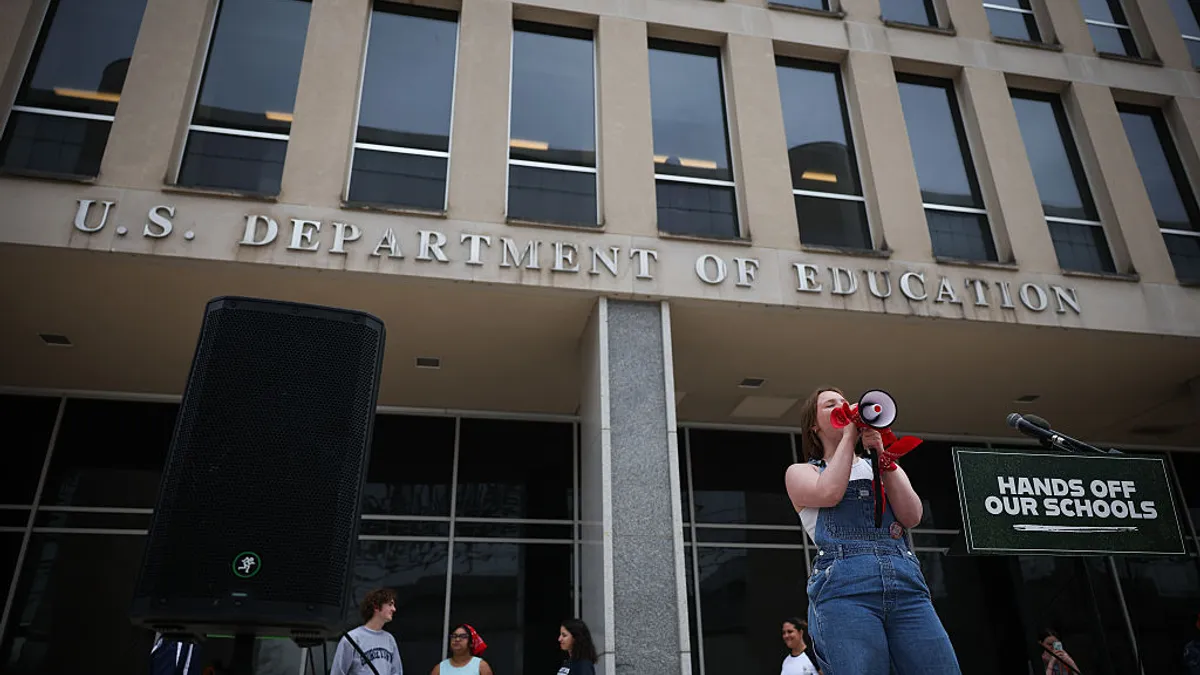

With so much public attention on diversity and inclusion, some districts are forging ahead with bold statements that may receive pushback. Others are feeling pressure to take their strategic efforts undercover. At Richland School District Two in South Carolina, we’re fortunate to be on a different path — one that has allowed us to successfully launch an initiative to recruit, retain, and elevate men of color within our classrooms.

Premier 100 is a blueprint for developing the next generation of education leaders of color, but it’s not a starting point. We’ve been connecting the dots toward this districtwide movement for several years. And even though 2021-22 was only our second cohort year, we can already see how it could lead to other initiatives in the future.

The educational backdrop

Richland Two is the fifth-largest district in South Carolina. Our student body is 61% African-American, 18.6% White, and 12% Hispanic. We were one of the first Purple Star school districts in the state because of our military connectedness: 13% of our students have family ties to the military. Our district’s history of desegregation goes back decades and includes one of the model schools for the Army’s own public school desegregation, which itself became a model for the rest of the U.S.

Within Richland Two’s 40 schools, we offer 39 magnet programs that give families a multitude of options. When we call ourselves a “district of choice,” it’s not aspirational — we have a dynamic and diverse environment. This diversity includes our teachers. By happenstance, we have a decent number of men of color in our classrooms, around 6%, which is three times the national average of only 2%.

We know inclusive experiences and diverse perspectives make a tremendous impact on students’ long-term academic success. Reflecting on the unique characteristics of Richland Two, I realized that by formalizing our unorganized-but-successful practices for recruiting and retaining men of color, our district could better position itself to serve students of all ethnicities, races, socioeconomic backgrounds, genders and abilities — and intentionally align with our district’s mission of developing the global citizens of tomorrow.

Equity work connects my passion and my purpose — and that’s where the inspiration for Premier 100 came from. When I was an assistant principal in this district, I never thought I would be a principal because I never saw any Black male principals. I’ve experienced the powerful shifts that can happen when you’re not thinking about barriers or constraints but are instead focused on academic leadership.

Laying the groundwork

Our school board members’ default mindset is that all students have the potential to be successful. They understand research about systemic factors that contribute to — and create barriers to — strong academic outcomes. We were the first public school district in the state to hire a diversity and equity officer and institute a board equity policy. All of that was a precursor to being able to start Premier 100.

Our community stands behind these efforts, too. We were already in dialogue about topics like implicit bias and privilege. Sometimes these interactions were difficult, but they opened the door to community conversations where we let our stakeholders take the lead. As a result, the atmosphere is receptive to new initiatives like Premier 100.

Our educators had already been doing work around culturally relevant pedagogy, including a partnership with the University of South Carolina, which taught courses and offered cultural experiences to teachers within our district. This was a springboard to Premier 100.

Finally, Richland Two had the essential assistance of the Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools and its Center for Inclusive Innovation, which created the Teachers of Color Recruitment and Retention initiative in 2020. Their focus on systems innovation is right up my alley; this work is in my blood and bones. Thanks to their support, I’ve been running at full speed.

Current significance and future possibilities

Premier 100 pairs a cadre of experienced Black male teachers with first- and second-year teachers throughout the district. These relationships are distinct from the young educators’ school-level mentors. Although those peer conversations are also important, Premier 100 provides a safe space where Black men can have conversations about their unique challenges. Although the pandemic limited some of the interactions, our inaugural cohort was still very successful. In two years, we’ve lost only four of 54 participants, and all of them became administrators.

That last phase, elevating, is crucial. We have to promote teachers as professionals, whether they stay in the classroom or transition to another position within the school. That doesn’t have to be administration — we were just talking within one of our Premier 100 groups about the need for Black and Hispanic male school psychologists. A few years ago, we weren’t talking about any of this, and now we’re intentional about what our district looks like in the long term.

We’re into the second cohort now, and we’ll start a third in the fall of 2022. But we won’t be able to fully evaluate Premier 100’s success for five or six years. How well we retain and elevate men of color down the road is the true test.