Dive Brief:

- Scaffolding can be an extremely useful tool for educators looking to design lessons that help students think and work more independently, according to Edutopia, which examined a 2019 Harvard Graduate School fo Education study on how students were able to best develop these skills.

- There were six specific scaffolds that helped students move forward in their learning and ability to work on their own. These include asking students to put what they’re learning into context, having students ask open-ended questions, encouraging them to take risks, and pushing students to be more thoughtful when hearing ideas that may not mirror their own.

- Teachers who use these approaches may be able to help guide students to take what they’re learning and apply those lessons in their next educational or real-life challenge.

Dive Insight:

Assigning students real-world projects can help them build critical thinking skills, and incorporating scaffolding can help guide them further while also deepening these skill sets, seeing them in a context of how they might potentially be used when faced with solving real-world problems at work or in the classroom.

Scaffolding is used at the university level, for example, to help students strengthen the skills they’ll need when they move on into the workplace, noted Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, in a 2018 Education Dive interview.

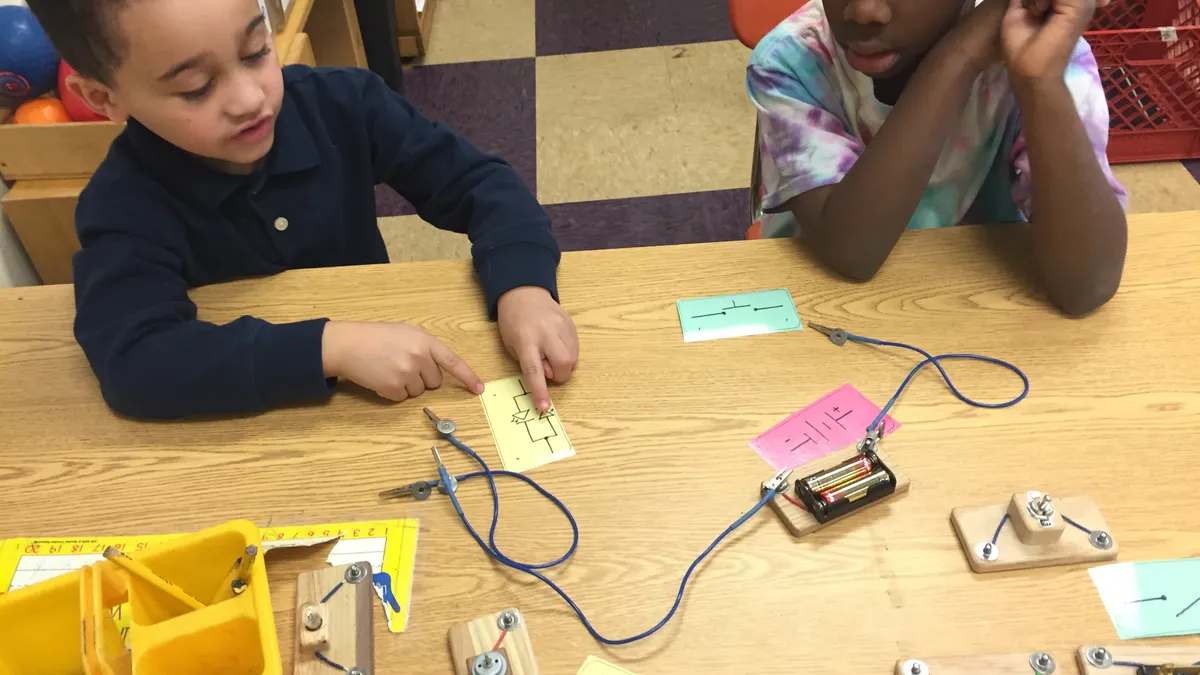

But the practice of scaffolding can also start as early as preschool, as undergraduates at Rollins College found while working with young children who were introduced to philosophical approaches so they could slow down and think more critically before making a decision about something they’ve heard. The students were supported, or scaffolded, as they developed this process through art projects and other activities in line with their age and grade.

Educators found children who ran through this practice were able to display patience and politeness when having a discussion — characteristics useful in a classroom and, of course, any workplace.

But implementing scaffolding can be time-intensive if it’s to be effective, as a 2015 study, “The effects of scaffolding in the classroom," found. There, “…its effectiveness depends, among other things, on the independent working time of the groups and students’ task effort,” researchers wrote. Sometimes high-intensive, or high-contingent, support worked. Other times, more frequent and low-contingent support worked.

Curriculum designers and administrators must decide which is more workable for their classrooms. Then, they must allow educators the time to develop the scaffolding they believe will best help students build critical thinking skills they will need moving forward in their education and beyond.